|

The smell of wood resin

and wood dust precedes William Kent's barn in Durham,

Connecticut by about 100 yards. As you make the final

turn on serpentine Howd Road—after passing cow pastures,

woodlands, vine-choked ponds and creeping suburbia—Kent's

lime-green door appears, a visual beacon that most people

simply speed past.

Why shouldn't they? They

have no way of knowing that inside lives and toils one

of the world's master artists. Private by nature, the

solitary William Kent once preferred it that way. But

now, having turned 82, Kent is beginning to wonder why

the larger world—meaning the major institutions dedicated

to art and culture—have not beaten a path to his

door. This is not just some idle pipe dream of a hobbyist

or second-rate talent but a valid complaint from a forgotten

master. William Kent, according to an art critic cited

in a New York Times article about him, is "the

world's greatest living carver of wood. There's not even

anyone close."

|

That, apparently, is part

of the problem. Woodcarvings and wood sculpture are not

"in" right now in the art world, nor have they been since,

well, Kent began carving in the late 1940s. Over half

a century later, he still can find no place to show his

work and only manages to keep afloat by selling a large

piece now and again to a die-hard collector who has been

led to Kent's door by one of his devotees.

If that seems implausible,

imagine how it feels to Kent, who rises each morning at

4:30, dons his wardrobe of sweatshirt, jeans and work

boots and then trudges the few dozen feet from his monk-like

living quarters to the frigidly cold barn. After working

for five hours, he takes a break for a light repast and

some relaxation playing the piano. Then he is back at

the wood—chipping, grinding, sanding, varnishing

and planning his next day's goal. His work ethic is as

astounding as his output.

Indeed, Kent carves wood

the way Picasso painted: striving for the simple but profound

beauty of form. In fact, he bears a passing physical resemblance

to Picasso and shares some of the master's Promethean

talent, as well as his penchant for not suffering fools.

"People look at my carvings and ask, 'What can you do

with it?' How do you answer that?" Kent resignedly offers,

"Wood carving is not fashionable. A narrow group runs

the art world, and I don't fit into it."

Despite some nagging minor

health problems, Kent looks about 20 years younger than

his age and is as vigorous in mind as he is in body. He's

a voracious reader of world history and philosophy, an

avid listener to opera and progressive radio and is more

informed on world events and political trends than most

of the so-called pundits.

"I think the Axis of Evil

is really the White House, the Supreme Court and Congress,"

he says, in one of his kinder, gentler assessments of

the current political scene.

***

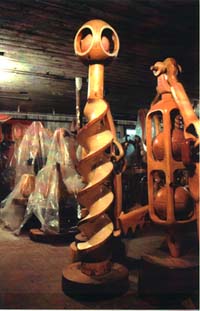

Like buried treasures,

hundreds of Kent’s carvings—most standing taller

than he—are stored under tarpaulins in his barn.

They are everyday objects he re-creates in wood: giant

shoehorns, pipes, ladles, vises, calipers, razors, safety

pins, plugs, eyeglasses, corkscrews, shoes, lightbulbs,

shell beans, bell peppers (one fashioned into a "Self

Portrait With Erection"), octopods, reptiles, dental plates.

This is not whittling on a grand scale but is, instead,

a complicated artistic process that produces all of five

or six complete works per year. Defying belief, most of

his sculptures are carved from single pieces of wood purchased

from sawmills.

The process starts with

a sketched idea, then a selection of the type of textured

wood he wants to use. Kent prefers "native wood" such

as poplar, red cedar, black walnut, white pine and mahogany,

but he's not afraid to use green wood or even telephone

poles. "Some idiot told me 'You can't carve green wood,'

but I've had chips fly off my carvings that were so green

they left wet marks on the floor," he explains.

|

Lately, Kent has been working

with different types of wood that he fuses together and

then carves, as if one huge block of wood. He just completed

a series of otherworldly shell beans "abstracted out and

laminated" with cherry in the center, poplar and walnut

around the edges. He has embarked on another series—eyeglasses

so large and wide that they seem, like World War I biplanes,

prepared to soar down the runway. Most of his carvings

are at least as tall as he is and include elegantly rendered

pedestals.

As he stands among

these remarkable creations, Kent begins to talk. He has

lived alone in this barn since 1964, when he was summarily

dismissed as curator of the John Slade Ely House in New

Haven for a showing of his erotic slate prints in a New

York gallery. As a graduate student at Yale, he studied

music under Paul Hindemith and began painting on his own.

He then moved on to printmaking; his carving arose naturally

from the cutting of slates for his prints. "I never studied

art at Yale," he says, with no sense of irony. "If I had,

I wouldn't be doing this kind of original work."

He has grown weary of the

"poor old man, curmudgeon, recluse" angle the media seems

to prefer when confronting someone in his current predicament.

This approach, he says, implies that his work is "not

good enough to sell, probably not commercially viable

in the first place, because everyone knows that if an

artist is good, he sells." Kent bristles at the suggestion

that he's "hiding" his work and produces a lengthy document

itemizing every rejection he's gotten since 1980. Among

the typical responses was one from Wesleyan (University)

Art Gallery: "We have to have credentials, Mr. Kent."

Or another from the New Britain Museum of American Art:

"repetitive." Or one from the lowly Mystic Seaport Gallery:

"We want something small we can sell."

|

Kent cannot be blamed for

recoiling at the process of approaching these sorts of

second-rate venues. But what really hurts is the utter

silence from the places where his work should be: the

National Gallery of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the

Hirschhorn, the Guggenheim, the Corcoran and the Whitney.

He would be no stranger to the Whitney. In the 1960s,

his slate prints of satiric and erotic subjects were included

in the Whitney Biannual next to work by Jasper Johns,

Robert Rauschenberg and Roy Lichtenstein. This did not

necessarily console him at the time, and it does nothing

for him now.

"Modern art has triumphed,"

says Kent, who views Johns, Warhol and Lichtenstein as

"the fashionable interior decorators of our time. When

they teach modern art in the Yale School of Design, you

know it's finished, a dead style. I can remember when

I came to Yale School of Music in 1944; modern art had

not touched Yale. They had a guy there called Eberhard,

who said he studied with Rodin. That was the style they

worked in at that time—tempura painting from the

Renaissance to the late 19th century. All of a sudden,

they flipped over and went modern when Joseph Albers came

in the 1950s."

Kent has no patience and,

in fact, a great deal of derision for the "sensationalist"

bent of contemporary art. "Museums have a right to show

that international garbage style…but like it or not,

doesn't my record of years of accomplishment, barely equaled

by few other artists around here, deserve some recognition?"

he asks, adding, "These sensationalist shows are here

today, gone tomorrow."

|

In recent years, Kent has

unenthusiastically enlisted the aid of art agents, with

mixed success. He gave up the effort when one of them

booked him at an "outsider art" exposition. "I seem to

be 'outside,' so to speak, because my work is so highly

finished. People look at it and say, 'Oh, it's craft work.'

Craft work? That's crazy. Look at a piece like this,"

he says, unwrapping a breathtaking work from 1961 of a

man kneeling with a wasp and praying mantis on his back,

all carved from one piece of black walnut. And another

work, from 1964, of a mahogany hand holding an alabaster

cricket. And another, from 1968, of a water faucet with

a chain flowing from its spigot—all made from one

piece of cedar. Still another, from the same year, of

an eagle with a duck's face seated on a trash can that

has tires so realistic you have to feel them to be sure

they're wood; at the duck's feet is a perfectly rendered

egg in alabaster, a zipper running along its top. "They

don't seem to accept this as art," he says. "That's what

I'm up against."

Despite the art establishment's

apathy, Kent's work shows no slackening in technique or

vision. In fact, it has never been better, evoking comparisons

to Rodin and Constantin Brancusi. He is a bit wary of

such comparisons, though, but not because he doesn't admire

these masters. He just thinks such comparisons are misleading.

"People have said that

I got my ideas from Brancusi, but where did Brancusi get

his idea for spiral forms? From African pole-carvings,"

says Kent. "Brancusi was a great influence, though. He

was the first major sculptor since Michelangelo to carve

directly into marble and other materials. Before Brancusi,

all the sculptors were either making plaster casts and

farming the work out to be made or using a pointing machine

to drill down into their medium and then cut out from

there. When I arrived at Yale in 1944, there was a big

pointing machine in the basement of the School of Art.

I never did that. I carve directly into the wood, like

Brancusi."

|

Asked, then, what his options

are, Kent simply says, "Do your work and die." Many of

his old friends have died. In his barn, hidden by plastic

tarps, are two oil portraits of Kent painted by friends

who both died in the past decade—Bill Skardon and

Sophie Cohen. The one by Skardon, a friend from Kent’s

Yale days, is particularly touching. Done in 1957, its

freshness and square-jawed virility nearly leap off the

wall, a glimpse of Kent's timeless aura of clarity.

Of his friend, Kent says,

"Bill was a fine artist, but he never had a break in the

art world. He studied art at Yale, but it didn't hurt

him much. He had his own individual style, so they couldn't

knock the originality out of him."

The comparisons to his

own situation are left unstated, hanging in the air with

the wood dust and the resin. "Someone told me, 'One day,

every museum will want one of these wood carvings.' But

not now. All the great artists went through the same thing.

Take Kandinsky. I just read a book," Kent begins, but

his voice trails off, as if he knows he's wasting his

breath. Or perhaps he has simply glanced above his bed,

where one of his slate prints hangs. On it are the words

of e.e. cummings: "Honesty Is The Best Poverty." This

could be the motto of William Kent.

Anyone

interested in Bill Kent's work can contact him directly

at 269 Howd Road, Durham, CT 06422, or 860-349-8047.

|