|

A couple of recent,

unrelated art stories seem to interconnect.

Sixty Old Master paintings

got chopped up, and Dr. Seuss's characters got cast in

everlasting bronze.

What's wrong with this

picture?

Here come enlargements

in the round of The Cat in the Hat and The Grinch in Springfield,

Mass., and there go one-of-a-kinds by Watteau, Boucher,

Bruegel and Cranach—stolen by Frenchman Stéphane

Breitwieser. His mother did the chopping.

And get this. While reports

about the reproductions of Seuss's children's book illustrations

go into their art qualities of line, color and shape,

those about the lost paintings mentioned only their monetary

value; i.e. the value of the Cranach painting was said

to be between $7.9 million and $9 million.

Period. Fat price. Thin

story.

We've all heard how art

is good for us. In school we're taught that it cultivates

us, polishes us and makes us better people. So why is

it that whenever fine art is written about in mainstream

media nowadays, money is the main idea?

|

|

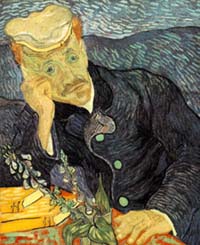

Van

Gogh's Portrait of Dr. Gachet

|

Some years ago, when a

pair of thieves robbed a museum in Boston of masterworks

by Rembrandt, Vermeer, Manet and Degas, the loss was described

in dollars—$200 million. When Picasso's "Nude in

a Black Armchair" got attention, it wasn't for the painting,

it was for the sale

price of $45.1 million. And when news reports came out

on the sale of Van Gogh's "Portrait of Dr. Gachet" for

$82.5 million, they omitted the significance of the picture.

They didn't mention that the doctor, who slumps in seeming

despair, attended the Van Gogh in his last days before

the artist shot himself.

It's no wonder, then, that

Washington Post columnist Henry Mitchell wrote

this about the Van Gogh sale:

The gall of some painters.

They point out that Vincent van Gogh never had two

dimes to rub together and here one of his pictures

has just been sold for $82.5 million. A number of

painters sleep and eat when they feel like it. They

punch no clocks, fill out no time cards... They are

as free as anybody else to sell a picture for millions.

All they have to do is convince some idiot its worth

it.

You have to wonder whether

Mitchell would have written that if reports of the sale

included something about the painting.

It's not that prices aren't

notable. They are. They imply the art's preciousness.

But in the recent case of the shredded canvases, where

is the information about what the paintings look like,

what they mean, how they stack up with the artists‚

others, with others by others? What happened to art's

reason for being—its ability to distill, codify and

deepen our sense of the world, of ourselves?

At one time, art was thought

to be as necessary to survival as food. Cave people put

their wall paintings on the same plane with hunting for

food. They believed that if they captured an animal's

likeness, the animal was as good as dead. Art was a kind

of magic, then. Picturing herds of bison and reindeer

was like an incantation for plentiful game. Showing animals

speared was a prayer for a successful hunt. Stone Age

artists hadn't tamed horses yet. They had to run down

their food on foot in hostile wilds and with the most

primitive of weapons. They needed magic. They found it

in their art.

Now art's magic seems lost

on us. Not only have dollar amounts become the main idea,

but originality has dropped from the picture: Old Master

art gets the money talk and mock-ups of children's book

illustrations get the art talk. Lost is art's sensory

experience—the scale, the brushwork.

Lost in the story of the

destroyed Cranach painting is how hypnotic it was. You

don't get the meticulously rendered detail. You don't

get the sensuality. You don't get how his brushed-on pigment

can move you to stand back, stung, in total disbelief

at the skill. And Cranach didn't even paint for a living.

He was a licensed apothecary by trade.

But here's the kicker.

The Greeks tried without success to find a paint that

would not lose its vibrancy. They and those who followed

had to be content with whites of eggs and vinegar, which

yellowed their work. Only in the early 14th century in

Flanders did the brothers Huybrecht and Jan van Eyck invent

oil paint by substituting linseed oil for the egg whites

and vinegar. Ever since, oil painting like Cranach's has

lasted in its original glory. It took an art thief's mother

to kill it.

And all the media could

talk about is its dollar value. I could cry.

|