|

Leonard Cohen in Montreal, playing country and western. Leonard Cohen in Havana, waiting for the revolution. Leonard Cohen in Hydra, hopped up on speed, shirtless, in front of a typewriter. Leonard Cohen in Manhattan, draped lazily with a woman across an unmade bed while the limousines wait in the street. Leonard Cohen in Tel Aviv, searching for the war. Leonard Cohen in Los Angeles, croak-whispering that he’s the little Jew who wrote the Bible. Leonard Cohen at the Mt. Baldy Zen monastery in northern California, singing to no one in particular.

Of all his work, it was the song "So Long, Marianne" that hooked me, with its playful, puff-of-wind melody. Catchy and infectious, yet sullen and mysterious, it sounded like the ‘60s hailing a cab into the ‘70s, "Soldier Boy" handing the baton to "Rocket Man". Yet, it really isn’t anyone but Leonard Cohen.

He was born on September 21, 1934 in Montreal. On that day, a few hours away in Toronto, my grandmother, Lily Cohen, was celebrating her twentieth birthday. They are of no relation, nor did she know of him when I first asked her in 1989. Despite this, I’ve enjoyed their similarities because, at the very least, it tenuously connected Leonard’s formative years to a world and culture with which I was a bit familiar. Understanding his starting point helped me appreciate his journey. The fact is that Cohen, from his simple name to his unobtrusive looks to his nondescript voice, is rather ordinary—which has given him even more mystery and depth than if he had been birthed into celebrity with the distinct name and cheekbones of an Elvis Presley or the wily unprettiness of the rather uncommon Bob Dylan. Like his counterparts in song, Leonard’s restlessness, his need to break out beyond his inherited wedge of the world, was evident from the beginning.

Nathan Cohen died in 1944, leaving 10-year old Leonard and his older sister Esther fatherless and their mother, Masha, as head of the family. His father’s death shaped Leonard’s poetry, which he began writing in 1949. According to biographer Ira Nadel’s book, Various Positions – A Life of Leonard Cohen, it was that year, "when he was fifteen, two important events occurred: he purchased a guitar and discovered [Spanish poet Federico Garcia] Lorca." Lorca’s effect was binding: "Cohen has ironically said that Lorca ‘ruined’ his life with his brooding vision and powerful verse."

While at McGill University, Cohen formed a country and western band, the Buckskin Boys. He was also president of the debating union and ZBT fraternity. It seemed that the prescribed academic life was an inconvenience, though, getting in the way of extracurricular, even intellectual, pursuits. Nadel writes that, initially, Cohen was on track for the white-collar success typical of the middle-class Jews of Montreal. But that would soon change. He began to write more and more poetry and was published in CIV/n, a Canadian literary magazine (the title being Ezra Pound’s abbreviation for "Civilization"). His first book of poetry, "Let Us Compare Mythologies," was published in 1956. He went on to Columbia University, where he continued writing and even started his own literary magazine, The Phoenix, which proved to be short-lived. By 1957, he was back in Montreal where, due to debt, he worked at his uncle’s clothing company while writing poetry and fiction. He gave poetry readings at nightclubs, backed by a jazz band. He soon quit his job at the clothing company, did some radio journalism for CBC and, in 1959, left for other lands.

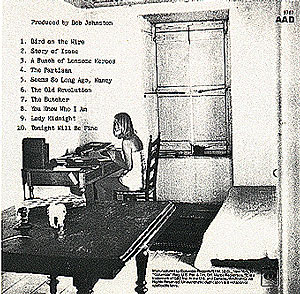

Cohen traveled around Europe, but it was when he landed in Athens, Greece and went on to Hydra that the unsettled vagabond poet found a place where he could hang his hat awhile. He paid $1,500 for a 200-year-old, five-story fixer-upper house. He also met Marianne, who became his lover and muse for a time and inspiration for the song, coming half a decade hence, that bids her adieu. In the narrow room with white walls, he wrote poetry and prose. This is the room that appears on the back of Songs from a Room, where Marianne sits at the typewriter, grinning at us. But back in 1960, he wasn’t yet writing music and would soon be publishing more books of poetry. The collection, The Spice-Box of the Earth, was published the following year.

Cohen made frequent trips back to Canada to make money and return to Hydra where the money stretched. He wrote the novel Beautiful Losers, which received some accolades but did not sell very well. In 1966, he moved to New York City and fell in with a crowd that included Joni Mitchell, Judy Collins, Dave Van Ronk, The Hawks (later to become "The Band") and more, a veritable "who’s who" of post-Beat/pre-hippie music culture. It was then that Leonard made the decision which put him on the path he’s been on ever since; his writing wasn’t supporting him, so he decided to try singing.

Like a bird, on a wire

Like a drunk in a midnight choir

I have tried in my way to be free.

"Bird on a Wire," (1969)

It’s often said that lyrics are just bad poetry set to music, and for Cohen, it is no exception. Whereas his poems often steer into melodrama, his early songwriting leaped ahead.

The album Songs of Leonard Cohen was released in 1968, and there was his voice for the world to contend with. A simple voice, almost utilitarian, pushing the words out, a melodic answer to the Method Acting adage: "Add nothing, deny nothing."

The albums continued over the next decade. Each had its own tone and style. Songs from a Room, the most basic of all Cohen albums, had his voice as barely a trickle on the tracks. It opens with one of his most famous songs, "Bird on a Wire", about which he has written, "I can’t seem to get it perfect. Kris Kristofferson informed me that I had stolen part of the melody from another Nashville writer. He also said that he’s putting the first couple of lines on his tombstone, and I’ll be hurt if he doesn’t."

Songs of Love and Hate featured protracted stories set to music, with a little spunk, but continued in a vein that can only be described as morose. "Famous Blue Raincoat" and "Joan of Arc," two of his best, are on this 1971 release. His first few albums may have been joked about as "music to kill yourself by," but they had an irrefutable, strong sense of self. 1974’s New Skin for the Old Ceremony broke out musically. Death of a Ladies’ Man began as a departure project, something a bit different from his previous, simply arranged collections of songs. It turned into a fiasco, with producer Phil Spector turning the project into something Cohen did not want, dropping his voice far back into the mix (as well as backing vocalists like Ronee Blakely, Alan Ginsberg and Bob Dylan), leaving little trace of what made Cohen music Cohen music. It is an album of little distinction, and Cohen himself disowned it. The album Recent Songs came in 1979, on the heels of his wife Suzanne (Elrod, not the namesake of his earlier song) leaving him and taking their son and daughter, Adam and Lorca, to Europe. The next album would not come for another half a decade.

Despite this, Cohen continued to write poetry and had several more books published. There have always been more fans of Cohen’s music than his poetry, and it seems fair to view his poetry book sales as a result of his musical success. His poetry can often be trite, as evidenced in "The Café" from 1978:

The beauty of my table.

The cracked marble top.

A brown-haired girl ten tables away.

Come with me.

I want to talk.

I’ve taken a drug that makes me want to talk.

Rather than the words of an accomplished lyricist and writer, poems such as this play like self-indulgent diary jottings. They seem to be missing the turns of phrase that come when the words are meant to be sung. Absent is the measured momentum that marks his best music. Many would agree, though maybe not the man himself, that Cohen is a musician who writes poetry in his spare time.

Now maybe there’s a God above,

but all I’ve ever learned from love

is how to shoot somebody who outdrew ya.

"Hallelujah" (1984)

In his 1993 song "Pennyroyal Tea", Kurt Cobain sang, "Give me a Leonard Cohen afterworld, so I can sigh eternally." It’s a lyric of innuendo; was Cobain referring to Cohen’s commitment to Buddhism in the last decade or his reputation as a dedicated lothario, a man whose summer of love spanned more than four decades? There was Marianne Ihlen and Suzanne Elrod in the ‘60s and ‘70s, a French photographer named Dominique Isserman in the ‘80s and actress Rebecca DeMornay into the 1990s. And according to biography as well as legend, many, many in between, all muses, feeding songs to Cohen who is able to convey intimacy in a way that few musicians can—expressing intimacy and sentimentality without being maudlin. "Nobody can sing the word ‘naked’ as nakedly as Cohen," author Tom Robbins wrote in the liner notes to the Cohen tribute album, Tower of Song. Wine, Women and Song; Sex, Drugs and Rock ‘n’ roll. Cohen has lived both the ancient and modern Dionysian creeds.

Since the end of the 1970s, Cohen’s relationship with Buddhism has had varying degrees of commitment. It may have been casual through the 1980s but became completely devotional when he moved into the Mt. Baldy Zen Center in 1993. Though he has always considered himself a Jew, according to biographer Ira Nadel, Cohen joined, full-time, the "isolated monastery, living in a sparsely furnished two-room cabin, his only comfort a synthesizer, a small radio and a narrow cot. He eats, prays and studies with the monks. Despite the meager surroundings, there is a richness of creative spirit and a pattern emerges that originated in Cohen’s youth. Once his life becomes too cluttered, he moves to an empty room."

It is tempting to employ simplistic motivations and causes to understand the choices others make. But it’s hard not to note how Cohen’s ascetic life seems a direct comment and acknowledgment that he has lived a full life of the flesh, yet he’s been unable to find a way to sustain love. Not atonement, but simply coming to terms with the past. A freeing of desire, as Buddhism teaches. The death of a ladies' man, to be sure.

All my friends are gone, my hair is grey,

I ache in the places I used to play.

"Tower of Song" (1988)

Photo by Laszio

|

The man is now old. Like Bob Dylan and his 1997 album Time Out of Mind, with songs like "Not Dark Yet," musings on mortality permeate much of Leonard Cohen’s work. Songs such as "If It Be Your Will," "Hallelujah" and "Tower of Song" speak of one’s getting on in years, of the endgame search for peace. But this sense of extra-worldliness comes from more than lyrics; between Recent Songs (1979) and Various Positions (1984), the sweet monotone ushered in a raspy, aloof, "voice-of-God" sound. The dark, crooning voice with no bottom is unrecognizable as the Leonard Cohen of youth. And the albums began to be more and more uneven. The songs on Various Positions had a more anthemic quality, which would be present in much of his subsequent work. The songs are all recorded with a single synthesizer and, unfortunately, this stifles it; the album, which features some potentially excellent music, to be sure, is nonetheless a prisoner of trends. Above all else, it has a lack of timelessness. Once freed of this tinny, at-home Casio synthesizer, the songs rise. This is most evident in "Hallelujah," which the late Jeff Buckley, on his 1994 album Grace, turned from a turgidly-rendered, plodding tune saddled with an overwrought, bombastic chorus into a beautifully haunting, transcendent prayer. If Cohen’s own execution was lacking, his songwriting certainly wasn’t.

His most recent albums of new material, I’m Your Man (1988) and The Future (1992) do have their gems. Indeed, the former has some of his best work—"First We Take Manhattan," "Everybody Knows" and the sublime "Take This Waltz"—and yet also includes the unnotable "I Can’t Forget" and the mistake, "Jazz Police." This is even truer for The Future, which has both the title track and "Waiting For the Miracle" but seems otherwise to be, in the parlance of the music industry, filler.

Regardless of whether that opinion is shared by all listeners, the fact remains that, by and large, the albums lack the personality and cohesiveness that marked Cohen’s earlier music through the end of the 1970s. Even Cohen Live (1994) showcases the stripping of the intimacy of his early work, replacing it with staid performances surrounded by overbearing back-up choruses. Rather than reinventing songs like "Suzanne" and "One of Us Cannot Be Wrong" for the times, they mainly sound uninspired, almost like—God forbid—wedding banquet entertainment.

We can try to pontificate and figure Cohen out, but we would be fools. That doesn’t stop us from trying, of course. The man gives us hints and eggs us on. About one of his most impressive songs, "Famous Blue Raincoat," he writes:

I had a good raincoat then, a Burberry I got in London in 1959. Elizabeth thought I looked like a spider in it. That was probably why she wouldn’t go to Greece with me. It hung more heroically when I took out the lining, and achieved glory when the frayed sleeves were repaired with a little leather. Things were clear. I knew how to dress in those days. It was stolen from Marianne’s loft in New York sometime during the early seventies. I wasn’t wearing it very much toward the end.

His fans read anecdotes and explanations like this, they listen to the lyrics and they piece together a life. Cohen’s listeners are detectives on his trail, and it would seem he likes it that way.

Among his serious fans, there are pilgrimages to his cities: last year to Montreal and to Hydra in 2002. A couple hundred people come together, tell stories, perform Cohen songs, retrace his steps and get a glimpse of the man’s world from days gone by. While there are more than a few musicians who gain this form of adoration—Jim Morrison and Elvis Presley among them—Cohen is one of the few, if not the only, to have earned official, organized festival "field trips" within his own lifetime.

His work is not finished; this past February, Columbia Records released Field Commander Cohen, an excellent live album from several 1979 concerts in London. And as of this writing, Cohen is out of the monastery, living in Los Angeles and working on his next record. This autumn, he will be 67 years old.

Click the image above to see this room as it appears today.

|

Leonard Cohen has been a minor poet by his own admission but a major singer-songwriter who is world famous, and yet virtually unknown, to hordes of popular music fans who worship the bands that count Cohen as an influence. His contributions to song have been hidden in plain view. Whereas some musicians have been trendsetters, he never seemed interested in all that. He just came in, sang his songs and left. He is a self-described "worker in song," and it doesn’t play like false modesty. He is not a darling of the Grammies. He is not fodder for karaoke. He has lived out of the bounds of sex, geography, religion and the music business and has created a mythology, flawed but enviable, along the way.

It all comes back to a man writing songs in a room, anonymous, in a foreign land. And the room is still there; in recent photographs, it is clean and bright. Vibrant with color and a CD player on the table—modernity rushing in. But in our hearts, it is grainy black and white, dark and fuzzy. Marianne shoots us a surreptitious smile. We try to reconcile it all.

|