|

It is the summer of 1976, and I am on the bus from hell. The gypsy should have warned me this was not the most auspicious moment to take a bus trip across eastern Iran, it being Miraj-Hazreti, the anniversary of the Ascent of the Prophet into heaven (for a chat with God, and other sacred beings). Under the circumstances my finicky, high-strung friend Barry is not the ideal traveling companion, either. Aside from his barely tamped-down hysteria, persnickety habits, paranoia, and insufferable whining, he’s recently taken a violent dislike to Iranians. All Iranians—across the board. I’m not that crazy about them either, and the feeling, judging from the time we’ve spent so far in Iran, is mutual. It’s going to be a very long trip to Afghanistan.

It’s not so much a bus we’ve boarded as the Cursed Ship of Islam, some demon-infested dhow (in which we’re the demons) filled with the blesséd soldiers of Allah chanting the song of our doom. A tape of some ranting mullah is blasting through the bus’s PA system at deafening volume. I can’t make out much but it’s hard to miss "the Great Satan"—even then we knew that meant us, the Other. Pairs of zealous fundamentalists bob their heads in hypnotic trance, chanting "Allah illah Allah" ceaselessly, endlessly. Hajjin with numbing cadence recite the formidable never-ending zikr—the repetition of the 99 secret names of Allah, a terrible celestial laundry list of incrementally shifting vowels that jams the gears of the mind. The bus hums with the dark joy of the impending ruin of the infidel. A sort of harmonic wolfbane that repels foreigners and makes them ill. An assault designed to drive us out, like vermin. We, who, it seems, cannot abide the repetition of the Prophet’s name, which to the true believer is like the ringing of celestial bells, honey of paradise.

Iranian Bus Pass

|

Outside the window of the bus is a howling desert, barren of all life. In Iran only 8% of the land is arable, and this particular patch is about as unarable as land gets. We’re on the border of the salt desert, Dasht-e Kavir. No flowering yucca or scurrying lizards here. More a desert’s idea of a desert, the barren preserve of sulfur sun beasts, where Islamic demons prowl and multiply, and from whence every evil and perverted twist of mind arises.

All you see by the roadside are brown stalks of grass with pieces of tissue waving from them like the flags of some desperate miniature tribe. The occasional bizarre monument pops up surrealistically in the middle of nowhere. Ghost villages. Broken domes like giant eggshells. The djinns had been busy out there in the empty quarter, creating their sullen and oppressive cenotaphs. Monstrous monuments shooting straight out of barren scrubland in the middle of nowhere. The rocket-like funeral tower at Gurgan, the obese, fluted obelisks of Qum, Max-Ernst-like pillars with long-winded inscriptions, all saying, "I am God, you are fools!" The pointless colossi of some conquest-mad Ozymandias.

The temperature inside the crowded bus is sweltering but opening the window is worse. In comes a fiery blast as if from some invisible furnace stoked by depraved djinns. The stench is stupefying. Sweat, rancid goat’s milk, and cheap eau de cologne. The two bleating goats tethered in the back of the bus and wooden crates filled with cackling chickens only add to the din and reek.

We are parched with thirst and like idiots have forgotten to bring any water with us. What were we thinking—twelve hours on a bus through a desert with nothing to drink? Never mind, in the Middle East you can always count on the kindness of strangers, can’t you? Except, that is, on holy days—and this happens to be the night when, thirteen hundred years ago, Mohammed ascended into heaven on his fiery horse.

I try in my best Farsi to beg a drink from my fellow passengers: "Ab, kh’hesh mi’ko’nam?" Please, some water? Well, under normal circumstances they’d love to, but so sorry, Infidel, not today. Infidel—do you see?—cannot drink from the same vessel as true believer. Some religion, this.

Ah, well. There’s bound to be a stop somewhere along the way. Five hours later the bus pulls into a bunker-like roadside canteen on the outskirts of Semnân. Inside, rows of institutional metal tables, robed figures like ghosts sitting at them. Their large dark eyes turn as one and stare at us with utter contempt. Well, you can’t expect the whole world to love you, now can you? We have a bigger problem on our hands. For some odd reason the people behind the counter won’t give us any food. They keep repeating, "Nesane, nesane" some Farsi word—one of many, actually, the meaning of which I have absolutely no clue. In heaven’s name, say what you mean, man! Oh, no, it can’t be, not the bloody infidel bit again, for Christ’s—uh, Allah’s sake. Look, we won’t use your sacred plates. Forget the bleeding plates, just throw the fuckin’ food. Nothing. Must be some misunderstanding. Ah, I’ll show them our money. We’ve got dollars, you stupid heathens (this in English). Look! Rial, travelers checks. "Havaleye posti!" we say foolishly brandishing our bits of printed paper. For god’s sake man, what do you want? "Ay shoma credit card?" We don’t actually have any, but it’s worth a try. Blank stares and that stupid word again.

As we’re boarding the bus I ask a kid in an Omaha State t-shirt why they wouldn’t serve us. "You must first buy tokens. Then pay for meal with token." Awright, we got the thing down now. Next stop Shârûd, four hours later. We dash into the restaurant and buy 100 tokens each. That should do it don’t you think? Yeah. What will 100 tokens buy you? I’ll tell you what it’ll buy: one bun and one apple. Ah well, never you worry, we’ll have a big bang-up feast when we get to Meshed.

I’ve let my mind wander somewhere along the line and the demonic chanting is starting to seep into my brain. I’m tired, I’m hungry, I’m disoriented and prey to the mind-dismantling mental harpies of Allah. This is my first encounter with fanatical Islam. At the beginning of this trip the chanting and the ranting seemed exotic, as a busload of Tibetan monks rattling prayer wheels might, but as the journey progressed it takes on an ominous cast. There’s an almost toxic aspect to it. The problem, you see, is that we aren’t part of the ummah, Mohammed’s word for the band of believers. We are outcasts, beyond the pale, and for that sin we’re being vibed out.

A born-too-late Beatnik, I’d gone to great lengths in my youth to align myself with outsiders—with mad people, drug addicts, hairy poets, peyote-chewing Indians, Hell’s Angels, and girls who dressed all in black and read Antonin Artaud. All this in opposition to the evils of bourgeois society (and my parents). But this was no intellectual pose; this was the brutal thing itself. Total immersion in a chilling form of exclusion. People to whom you are so alien and repugnant that they wish you dead—they are aiming their lethal rays at you. It’s suffocating, as if I’ve caught a virus.

The only thing to do is to give in to it, hook onto the sine-wave of mad devotion and float along on its manic slipstream. Submit to Islam—the word itself meaning "surrender"—or be cast out. Or worse. But not Barry. A displaced person to begin with, his psychic membrane is very thin. He’s gotten very quiet and small. Like the rabbit with myxomatosis in the Philip Larkin poem: "You may have thought things would come right again/If you could only keep quite still and wait." Just looking into his swirling eyes, I can see his inner creature is in a state of imploding panic.

"I feel like they’re sucking out my very soul," he says mournfully.

"Well they probably are, actually, but luckily there’s a way round it. They’ve developed these little pills now that allow you to bypass the soul entirely." I handed him a dilaudid. I’d got a bottle of them at a pharmacy in Teheran—in case of dysentery, you know. In Iran you don’t need a prescription for anything, you just walk in to the chemist’s and point to what you want.

"What does it do?" Barry wants to know.

"Listen, at the bottom of it all," I tell him, "We’re just a net of neurons with intention and this will help you focus on that aspect rather than on the nagging ontological uncertainties that plague one at times like these."

"Fuck off."

"Go on, take it, you’ll feel better, really. It attacks the higher centers of pain. It’s pharmaceutical heroin, basically." Even narcoticized, Barry is still collapsing. Bits of him are falling off.

The bus slows down as we approach a small village. Barry gets up, his eyes spinning.

"I’m getting off," he says with zombie-like intonation.

"What do you mean, you’re getting off? Don’t be silly. You know you’ll never be heard of again," I tell him. "I understand there are cannibals in this part of Iran. You’ll be sold into white slavery, you’ll never be able to use your left hand again."

"I don’t care. I can’t take this anymore."

"Very well, then," I say with sham equanimity, "I can see you’ve made your mind up. Before you go though, you better give me any film you’ve shot. That way, I may be able to arrange for a little memorial exhibit of your work in one of galleries around Tompkins Square. Who knows, you may even get a little blurb in the Village Voice."

Just outside the village we are waved down by Savak, Iranian secret police. By the time the thuggish-looking gentlemen with the AK-47s get on the bus and have removed several of the passengers for interrogation, Barry had changed his mind. Oh, have I mentioned this all this took place on the eve of the Iranian revolution? Yes, things have hotted up quite a bit in Iran.

Night falls. There’s a crescent moon outside, just like the one that guided Mohammed on his flight to Medina. The stars come out. Distant hills. The night belongs to lovers but the Persian blue-black night with its stage-prop crescent moon belongs to Islam. Under such a moon in 1453 the Turks conquered Constantinople, and by its light Layla and Madjnun kissed for the last time under her father’s window.

How is this night different from all other nights? This, children, is Miraj-Hazreti, when the Archangel Gabriel awoke Mohammed and took him on a mystic night journey on the back of a white, wingéd horse-like creature called El Burak ("Lightning") to Mt. Sinai, then on to Bethlehem and, finally—giddyap Lightning!—to the Dome of the Rock. Here Mohammed met Adam and Abraham and Moses and Jesus (Isa). From there a ladder of golden light materialized, and he made his spiritual ascent through the seven heavens to the holy dimension of astrological space, arsh al-ala, and there communed with Allah.

There’s a folktale element to the tales in Islamic theology, which includes the life of Mohammed: little animated Persian miniatures—night, a crescent moon, the horse El Burak with its fantastic wings and exquisite little face, Mohammed riding serenely to his celestial destiny. The other side of the coin is the Qur’an (literally "the Recitation") with its truly bizarre utterances, curses on the evil-doers, oracular pronouncements, the Bible re-written by Andre Breton. The surrealism of the Qur’an is endemic, it’s catching—the Surahs of the Bee, the Ant, the Folded Up, the Fig, the Clot. It’s as if everything were seen through a convex mirror: the music, the art, the mosques and minarets all slightly out of phase; a hallucinated geometry of Otherness. As if under the hot wind of the enigmatic, the very names of middle-eastern towns are stunted into gnarled, droll Beckett-like phonemes: Swat, Qum, Merv.

Not that there aren’t plenty of strange things in the Bible, too. But there’s a difference. The oracular attack in the Qur’an is baffling. In comparison, the Diamond Sutra of the Buddha seems as clear as day. The Qur’an is a hermetic text, it presents revelation of divine mysteries as only partially available to common sense—as one might expect from a supernatural document. How could we mortals ever completely comprehend the mysterium tremendum? Whose very oddity is its guarantee that it comes from a source utterly alien to us. It obeys the laws not of human but of celestial syntax.

And it’s just this very cryptic compression at the core of Islamic belief, and its offspring, zealous fury, that is so disturbing to a Westerner. A lot has been said recently about the pacific nature of Islam and this is true as far as it goes—prohibitions against murdering civilians, even against the wanton destruction of trees—although there’s still plenty of eye-gauging, "slay the idolaters," and other dire threats against the Unbeliever in the Qur’an. The Prophet himself was given to outbursts of homicidal paranoia worthy of Saddam Hussein. "Thirty impostors shall arise in my Ummah," he predicts, and you know with horrible certainty what’s going to become of those impostors.

His first terrifying act of aggression was the casting out into the desert of two of the Jewish tribes of Medina (the third tribe meeting a worse fate still: the men were beheaded and the women and children sold into slavery). By the time he conquered the Jewish settlement at Khaibar, 150 miles north of Medina, he was in the protection racket, extorting tribute from Jews who refused to convert. By the sixteenth century Islam had conquered half the world in the name of Allah, not exactly in the same spirit of, shall we say, Asoka, the Buddhist reformer who abandoned war (after conquering half of his world) in favor of converting the heathen by spiritual example. The good book may say what it wishes; world-scourging maniacs will do as they please.

A rather graphic reminder of just how brutish and violent the jihads of early middle ages of Islam could be is the twelfth-century sword I bought in Tabriz. It’s a heavy, limb-hacking kind of weapon with a fluted groove down the center for the blood to run off and the words of the prophet incised on the blade—just to remind the enthused butcher in question why exactly he’s slicing up some poor Parthian fellaheen.

South of Maku

|

Fourteen hours of pounding Islamic ordnance on the bus and I’m beginning to understand what losing your mind means. I can feel my brain cells scattering. It’s getting to me, the collective curse of the tribe, the anthill, the swarm, the ummah. The hive of Allah has arisen and is swarming over the desert. It has its own reasons. The voice of We. We are all. The terrible choir. The hum of the ummah that will disturb the world’s sleep. The first inklings and rumblings of the Ayatollah’s revolution. The first sound of creaking tumbrels, the first gushing of the fountain of blood.

Sweat from heat and fear is pouring down my face. The sensation of being brainwashed, of being physically crushed, finding it harder to breathe, of falling endlessly down a mindshaft which has no bottom. The terrible lurch when your equilibrium fails you: "And then a Plank of Reason broke/And I dropped down, and down—"

Momentarily I resist the onslaught of the satanic voices. I am the schoolteacher Gordon Zellaby (played by George Sanders in the movie) thinking of a brick wall in order to block the lethal mind-rays of the eerie blonde telepathic identical children in Village of the Damned.

I look over at Barry and see he’s beginning to close down, he’s breaking up from the sense of valuelessness brought on by this unrelenting rejection cantata.

"Get a grip," I tell him, speaking as much to myself as to Barry.

"My bones are shrinking," he says with a sepulchral sigh. He did seem to be getting smaller actually but best not to encourage him in this line of thought.

"It’s probably just the dilaudid coming on," I reassure him.

"We’re doomed."

"Look," I say, "this sinking into morbidity business is going to get us nowhere. Try and think of something cheerful, like, er, the San Gennaro festival on a hot summer night, Central Park on the first warm day in spring with the crocuses blooming and—"

"Don’t be stupid. You sound like Dr. Joyce Brothers. The trouble with you is that just because you can manage a bit of Farsi and have figured out how to loot Iranian drugstores you think you’re in control of things, whereas you are actually totally deluded—to the point where you don’t know the difference between what’s real and what’s in your head."

He has a point but I prefer not to dwell on it. Perhaps reading to Barry from the guide book will calm him down: "Did you know that Meshed is the birthplace—more or less—of Omar Kayyam?" Ah, an opportunity to quote from the Edward Fitzgerald translation of the Rubaiyat I was forced to learn by heart as a child:

One Moment in Annihilation’s Waste,

One Moment of the Well of Life to taste—

The Stars are setting and the Caravan

Starts out for the Dawn of Nothing—Oh, make haste!

In order to cheer the supercilious bugger up a bit I show him a photograph of a truly hideous example of kitschy modern Iranian architecture: a sort of twisted lattice-pie-crust thing in cement and brass celebrating some atrocity by the house of Pahlavi, the dynasty of the current Shah. Barry is suitably appalled. He shakes his head in disgust. Good, I’ve managed to distract him. I press on. "Look," I say showing him an ancient, bunting-festooned sarcophagus. "It’s in Meshed, the tomb of the ninth-century Islamic martyr Imam Reza, a site of devout pilgrimage for Shiites, making it one of the holiest places in all of Islam." Little did we know what this meant—on a night like this.

We arrive in Meshed. A mildly festive air. Children with tasseled toy horses, like the El Barak. But these festivities are not for us. If anything, the Meshedin are even more into the Prophet’s Ascent than the zealots we’d encountered on the bus. In Meshed we aren’t even allowed to enter a restaurant, much less eat there. At the door of one restaurant I cry, "Ab, insha’ Allah!" in a piteous voice. For the love of Allah, at least let us have a glass of water! The wretch who runs the place points to a spigot outside near the pavement and we like dogs get down on our knees and drink from it. The jeering patrons inside the restaurant laugh. We are truly infidel dogs, something less than human.

This is too much for Barry. He returns to the bus station and lies down on the ground with his arms crossed over his chest as if ready for mummification.

"I’m not moving," he announces with finality.

"Oh, c’mon, Barry, buck up. Whatever we do, we’ve gotta get of here, man, before they kill us and eat us."

"You go on. Leave me here, you’ll have a better chance without me."

I tell him this won’t do, just bad B-movie dialog. Departing, I quote some timely Omar Kayyam: "the Bird of Time has but a little way/To fly—and Lo! the Bird is on the wing." I leave him there to meet his Maker, and go out into the night.

After wandering aimlessly about for a while I come across a nest of gorgeously decorated Afghan trucks. Cosmic clowns of the old silk road! Ceremonial and giddy at the same time, very jolly lorries in a Hindu festival. You’ve seen them, these fantastically decorated little temples on wheels, yes? Decorated with bells, tassels, rosettes, suns and moons, eyes, trains, planes, cobras, gondolas, lions, fish, telephones, Qur’ans, oases, tiger scribes, Taj Mahals, exotic birds, dancing girls, prancing palm trees. Cheerful, extravagant, friendly, they seem to say, "Very joyful to be of service, Babu!" The Afghani is quite a horse of another color from the grim, puritanical Iranian, although his heart, too, leaps at the sight of brightly-painted gewgaws.

My spirits raised by my encounter with these fantastic creations I am walking back to the bus station to tell Barry about them when a skinny kid in a green sharkskin suit crosses in front of me and with a great theatrical flourish. "Sa’lam," he says, "Welcome to Meshed!"

Just what we need, an Iranian hustler. Harun, our savior. I take my new friend back to meet Barry. "What does the little scam artist want?" Barry asks. He wouldn’t take any money. But he likes my camera and my watch, neither of which are exactly functioning, but I tell him he’s welcome to them. Harun finds us a place to stay, gets us some food, which we eat in a park, and quotes some Omar Kayyam in Farsi; an enterprising and poetic fellow.

Next morning Harun hooks us up with a truck driver who is going to Herat. Soon, we’re on our way to Afghanistan in one of those trucks. Loud music on a cassette player whose batteries are winding down. Whatever the song had started out as, it now sounds like an Alan Hovaness whale concerto.

Finally we reach the border. First comes the grisly Iranian customs’ Hall of Horrors. Little dioramas of smugglers who’ve been caught in the act. Giant-blown up photos of hippies in flowered shirts, sheepish businessmen in shabby three-piece suits, Afghanis in turbans, college kids in polo shirts, sad-faced girls in Marimekko saris, all ruthlessly exposed in a flash-bulb terror instant. In front of the blow-ups are the objects in which the smugglers have ingeniously concealed their contraband: heels of shoes, tubes of toothpaste, hollowed-out tennis racket handles, gas tanks.

But why exactly would anyone have to smuggle this stuff into Iran, itself a major producer of opium, hashish, etc. It isn’t explained. Afghani customs officers are, by contrast, a cheerful lot. "Anything to declare? Guitar? Girlfriend? Ba’sal’a’ma’ti! Good luck to you sir!" As you exit a sign announces: "no alcohol allowed. except in the case of embassies where it is necessary."

Once in Afghanistan, our driver makes a few stops on the way. Why the hurry? This very good chai house. We have good luck here. Men sit gossiping at low tables, laughing and talking in turbans and traditional garb, pantaloons and shirts with long tails, back and front. Part of the get-up designed for Islamic males to give birth to the next Messiah. And they make fun of the Virgin birth! Also on menu: as well as delicious chai, here we are serving at your pleasure best quality Herat province hashish, opiated or plain, according to your liking. Everything very jolly good.

Finally we approach the fabled city of Herat. I’d brought some windowpane acid along with the intention of taking some when I arrived there. I take out a piece of the yellow stamp-like acid printed with a Tibetan thunderbolt design. Barry is horrified.

"You took this stuff through Iranian customs? Twice?"

"I forgot I had it, to tell you the truth."

"Well you’re not taking it here. You’re not going to leave me stranded in this God-forsaken place while you wander off talking to snakes and trees."

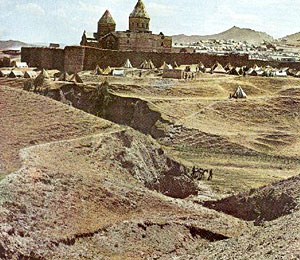

He needn’t have worried. I was already in ecstasy. Before me stood the gates of a walled city, but not in the sense of "remains of the old city wall can be seen.…" This was a complete medieval city surrounded by sixty-foot walls, set on massive prehistoric earthworks with six huge crenellated towers that were straight out of King Arthur. In the center of the city the houses were of mud brick, with soft earth colors: ochre, burnt umber, raw sienna. Powdery browns and yellows, just as Edward Lear’s cook had described Petra as made of spices: walls of saffron, cinnamon, ginger, and curry.

A woman is carrying water from the well in a brass pot (there are no water mains in Herat), a turbaned Tajik tribesman on horseback with bow and arrow is sitting high in the saddle with the grace and elegance you see in Edward Curtis’s photos of Native Americans of the Great Plains. It’s as if time had stopped. Nothing has changed here in 1,000, 2,000, 4,000 years. Tripping is clearly superfluous under these circumstances. This is a trip. We are in a city straight out of The Thousand and One Nights. The djinn and caliph-haunted East I’d dreamt about since I was a child, come fantastically to life.

Check back in two weeks for Part II of "An Infidel in Afghanistan."

|