|

Last I heard about him he was in New York, and Jerry Ragovoy used to produce him. He made all these demos with the guy and I asked Ragovoy, "Where in the world is Howard Tate?" And he wouldn’t tell me. So he’s either in jail or dead or just not working in music which seems unlikely because the guy’s so great. There’s never been any better than Howard Tate. Fantastic!

—Ry Cooder, 1981 (from an interview conducted by the writer)

I can’t exactly remember when I first heard Howard Tate. Somewhere back in a now-hazy teenaged memory I recall riding around North Jersey suburbs listening to the AM soul station out of Newark and hearing "Ain’t Nobody Home" and "Look At Granny Run Run" and knowing they were like nothing else, bluesier, just as funky as what was coming out of Memphis and every bit as soulful. I can’t exactly remember when I first heard Howard Tate. Somewhere back in a now-hazy teenaged memory I recall riding around North Jersey suburbs listening to the AM soul station out of Newark and hearing "Ain’t Nobody Home" and "Look At Granny Run Run" and knowing they were like nothing else, bluesier, just as funky as what was coming out of Memphis and every bit as soulful.

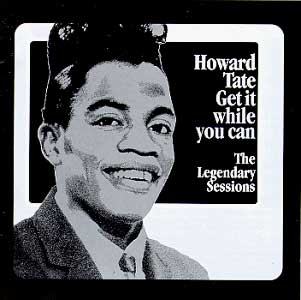

By the end of the ’60s or early ’70, I had Tate’s first album, Get It While You Can, which quickly became one of the most treasured in my collection. The cover was reason enough to own it. Purple and blue with a big black and white photo of Tate, tinted in blue. Skinny, smiling, he had one of the wildest pompadours on any singer before or since.

It was his voice that grabbed you. Straight from the church—B.B. King and Sam Cooke rolled into one but more energized, with perfect phrasing and emotion to spare, capped by an amazing falsetto he called on at just the right moments. And while it was soul music, there was a strong blues current behind it that wrapped it up and took it home, leaving no doubt that this was the real deal. Janis Joplin would later record the title track, one of the great heartbreaking soul ballads of all time on what turned out to be her final album, Pearl, and it would be a huge hit.

The more I listened, the more I became convinced that Tate was one of the greatest soul and blues singers I’d ever heard, right up there with Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, Bobby Bland, Ray Charles and Solomon Burke. The man had presence and power to spare.

Some time later in the ’70s, I found another Tate album, this time on Atlantic, simply titled Howard Tate. The wild pompadour had been replaced by an Afro. Like the first album, it was produced by Jerry Ragovoy, who wrote most of the songs and arrangements. There were three songs I immediately recognized: "Where Did My Baby Go," which I had on a single by the Butterfield Blues Band and, curiously enough, the Band’s "Jemima Surrender" and Dylan’s "Girl From The North Country," arranged as a soul song. On it, Tate let loose, wildly stretching out lines till they were about to break, seeming almost out of control and then snapping back just in time.

This time, the musicians were listed. They turned out to be some of the finest session men in New York—names like Richard Tee, Eric Gale, Bernard "Pretty Purdie," Jerry Jermott, David Spinozza and Rick Marotta, to name a few. The sound in general is a bit cleaner than the Verve album, but Tate’s vocals and Ragovoy’s arrangements had the same intensity. This time, the musicians were listed. They turned out to be some of the finest session men in New York—names like Richard Tee, Eric Gale, Bernard "Pretty Purdie," Jerry Jermott, David Spinozza and Rick Marotta, to name a few. The sound in general is a bit cleaner than the Verve album, but Tate’s vocals and Ragovoy’s arrangements had the same intensity.

Around this time, I began to wonder, who is this guy and where is he? I knew he was from Philly and, when he had his first few hits, he was dubbed "The Soul Mayor of Philadelphia" since the mayor at that time was James H. Tate. Every year I’d look in the Philly phone book, but Howard or even H. Tate was never listed. Some people I knew even went up to North Philly and talked to members of the Dixie Hummingbirds. But no one knew.

Some time later while browsing cut-out bins in a record store, I found a third Tate album (which was actually his second), Howard Tate Reaction, on Lloyd Price Turntable Records, produced by Price and Johnny Nash and, according to the info on the cover, recorded in Jamaica. The arrangements had none of Ragovoy’s precision. In addition to a reggae, "Hold Me Tight," there were a lot of covers of old soul songs, with a slowed-down version of Sam Cooke’s "Chain Gang" being the standout.

Decades passed, and every once in a while I’d have fun playing Tate for friends who didn’t know about him. In 1993, Rhino wisely put "Girl From The North Country" on a compilation called Black On White (subtitled "Great R&B Covers of Rock Classics"). And in 1995 Mercury reissued the original Verve album on CD, with an additional seven bonus tracks. But it seemed like that was the legacy of Howard Tate. What happened to someone who was easily one of the greatest soul singers of all time remained a mystery.

But last Easter Sunday, while I was eating breakfast and reading the Sunday Philadelphia Inquirer, I turned to the second section and was stunned to see an article on Howard Tate. He was alive and a minister in South Jersey.

Phil Casden, a disc jockey who had a weekly show on WNJC in Washington, NJ, would regularly ask listeners for information on Howard Tate. On New Year’s Day, Ron Kennedy, a former singer in Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes, spotted Tate in a supermarket and told him to call Casden. Tate was soon reunited with producer Jerry Ragovoy and appeared in New Orleans during the Jazz & Heritage Festival.

On July 21st, Tate played his first New York date in three decades at the Village Underground. And I made sure I was there. I’d spent the past month trying to convince people to go see this singer they’d never heard of, and I wondered myself if he could still do it. When Tate walked on stage and the Uptown Horns blasted into "Stop" (a song later covered by Al Kooper and Mike Bloomfield), there was no doubt. It was as if he had recorded the song the day before, instead of in 1967. The pleading intensity in his voice and the falsetto were intact, and the arrangement seemed exactly the same. And there was nothing in the show to suggest an oldies show—some old singer revisiting his past. It was a real R&B show, the way they used to be. It was as if somehow, except for looking older, he had been suspended in time and then he appeared to deliver the goods. Jerry Ragovoy was in the audience, and Tate was more than happy to acknowledge him. On July 21st, Tate played his first New York date in three decades at the Village Underground. And I made sure I was there. I’d spent the past month trying to convince people to go see this singer they’d never heard of, and I wondered myself if he could still do it. When Tate walked on stage and the Uptown Horns blasted into "Stop" (a song later covered by Al Kooper and Mike Bloomfield), there was no doubt. It was as if he had recorded the song the day before, instead of in 1967. The pleading intensity in his voice and the falsetto were intact, and the arrangement seemed exactly the same. And there was nothing in the show to suggest an oldies show—some old singer revisiting his past. It was a real R&B show, the way they used to be. It was as if somehow, except for looking older, he had been suspended in time and then he appeared to deliver the goods. Jerry Ragovoy was in the audience, and Tate was more than happy to acknowledge him.

Tate played what seemed like the entire Get It While You Can album, a couple of songs from the Atlantic album and, as if to prove he was here to stay, two new songs. One, "Sorry, Wrong Number" had classic written all over it.

A few weeks after the show, I found myself sitting in Howard Tate’s living room in a New Jersey suburb northeast of downtown Philly. The furnishings were sparse. A guitar case was on the floor, and there were piles of CDs on the coffee table, on the floor, on another table. A computer was in one corner with a scrolling "Jesus Saves" screensaver. His cat played near us on the floor.

Tate was friendly, relaxed and eager to talk about anything except the years he was out of sight. His recall seemed excellent, and he seemed aware of what was going on in music during his lost years. At one point I mentioned Ry Cooder, and he responded immediately with, "He did ‘Look At Granny Run.’" Tate was friendly, relaxed and eager to talk about anything except the years he was out of sight. His recall seemed excellent, and he seemed aware of what was going on in music during his lost years. At one point I mentioned Ry Cooder, and he responded immediately with, "He did ‘Look At Granny Run.’"

I’d like to start at the beginning. You were born in Macon—when was that?

1939. August the 14th, 1939. I started singing around the age of, I guess, six or seven in my father’s church. He was a minister, and I used to sing around the house, and he’d hear me trying to sing. I loved the gospel groups of that day, the Nightingales, the Dixie Hummingbirds, Sam Cooke and the Soul Stirrers. So he said to me one day, "Why don’t you learn a song and sing before I bring the sermon? Why don’t you sing a song? So I started learning the gospels, and I started singing before he would bring the sermons, and that’s how it all started. The Sensational Nightingales were one of my favorite groups… this is what really had the most impact on me starting out singing, and they had a lot of influence on my deciding to start singing and created a great interest because I loved to hear them sing.

How did you end up in Philly?

Well, we migrated from the South when I was just about 4 years old; my parents migrated here because of trying to do better economically ’cause farming was a way of life in the Deep South in those days and the opportunity for employment and economic growth was greater in the North. And that’s how we migrated to Philadelphia.

You sang with the Gainors and Garnett Mimms?

Yes. The Nightingales’ bass singer sang with the Gainors also. And Garnett Mimms, who went on to record a big multi-million seller, "Cry Baby," Sam Bell, a guy named Willie Combo and I, we made up the Gainors. And as I said, one of my big heroes who was the bass singer with the Sensational Nightingales, he came off the road from traveling with the Sensational Nightingales, and he wanted to sing spirituals around Philadelphia and he joined our group, who later became the Gainors. We were in a group called the Bel Aires, and Mercury sent a talent scout down to Philadelphia one night to sit in the back of the church. And that’s where they came, the big record companies, to recruit talent, and they felt the best talent came out of the church. And they heard us singing and they wanted to record us, and they changed our name from the Bel Aires to the Gainors.

You were also with Bill Doggett?

I was with Bill Doggett after singing with the Gainors and recording several records on the Mercury label. We were produced by Clyde Otis, who at that time was producing Brook Benton, also. We weren’t very successful with Mercury, and I decided to leave the group and go on the road with Bill Doggett. He heard me singing one night in a club, VPA in Philadelphia, which happened to be right next door to the Uptown Theater where Georgie Woods [a famous Philly disc jockey and show promoter] brought all the big shows in. I was next door singing in the VPA one night, and Bill Doggett came through town. Not knowingly, he was looking for a blues singer to travel with his band. I had no knowledge of that at the time. But I happened to be singing a blues that night, one of B.B. King’s songs, a song called "Sweet 16." Bill heard me singing it and it went over rather well, and he sent for me and said he was interested in me coming to New York to talk to him about joinin’ his band. So we set up the appointment. I went into New York the next week and he wanted me to join the band, meet the band in Savannah, Georgia the following week. And I agreed to that. We agreed on money and a weekly salary and that type of thing. And I joined the Bill Doggett Band at that point and met them in Savannah, Georgia the very next week. And I was with Bill Doggett, I guess, two years. Traveled all over the country.

Okay, that leads into my next question. Particularly on the Verve album, there’s a very strong blues influence, more so than, say, a lot of the other soul singers at the time. Who did you listen to in blues?

Well, I listened to B.B. King, who was my favorite. I loved all the blues artists, and I listened to Johnny Taylor, "Part Time Love," I believe he made that first and they was two of my favorite blues artists. And when we decided to do the Verve album, I talked to Ragovoy about that. I says, "Hey Jerry, why don’t we give a listen to these two blues," and he liked them. He says, "Let’s do ’em. You know, you sound great on ’em." And I love the arrangements he put on those because even though we did those blues, he put somethin’ on them, he brought somethin’ to the table with those two songs that was between gospel, jazz and blues was in the middle and made it a little different. Because he would put those extensions on them, and they just blew your mind. And, in fact, it blows all the musicians’ minds all over the world, those extensions that Ragovoy writes when he writes those arrangements.

How did you hook up with Jerry Ragovoy?

After I come off the road with Bill Doggett, the reason I left Bill Doggett, Atlantic Records had been trying to sign me to record with Bill Doggett, and Bill wouldn’t agree for me to go with Atlantic. So I got fed up with it. I said, "Well, I’m leavin’ the band." I went back home. And when I got home, the second day home, Sam Bell came by the house. He had a record in his hand from United Artists, and he says, "We just made this record." It was called "Cry Baby." And a guy named Jerry Ragovoy produced it. Well, in about a week, that record was hittin’ everywhere all over the world. That was one of the biggest records ever, went to number two in the Billboard Hot Hundred. And Ragovoy was lookin’ for talent, and Garnett Mimms and Sam Bell said, "This guy Howard has a great voice." They let him hear some of my tapes, and he fell in love with the voice. So they contacted Georgie Woods, who was a disc jockey in Philadelphia at that time, and said, "See if you can locate Howard for us." So Georgie Woods went on the radio and he was announcin’ somethin’ like hour on the hour, "If Howard Tate’s out there or anyone knows where Howard Tate is, have him call Georgie Woods." Well, somebody got in touch with me, told me he was lookin’ for me. I called him up, he says, "Get in touch with Bill Fox," who was Jerry’s partner, and I got in touch with Bill Fox, and he says, "Call Jerry Ragovoy, he’s interested in recordin’ you." When I called Jerry, he said, "Can you come into New York?" I went in to New York, I signed with them and that’s how we met and that’s how it started.

Jerry Ragavoy and Howard Tate in the studio.

|

When they released "Ain’t Nobody Home," that record was out and I was doin’ construction work and I was mixin’ mortar for 15 bricklayers and they were about to kill me because tryin’ to supply 15 bricklayers with mortar and bricks will work you till your tongue hang out. So I come home from work and mortar all over my face and mortar all over my boots from mixing that mortar all day, and I was dog tired. And I saw this Cadillac sittin’ in front of the door. It was Bill Fox. And he blew the horn as I was goin’ up the steps, and I went over and said, "Hi Bill, what’s up?" And he says, "You gotta go to Detroit. Right away! The record just went to number one in several of the key markets, and Detroit is one." I said, "Well, all right. Can I shower first?" He says, "You don’t have time for that. You gotta catch the plane, and the flight’s gonna be leavin’, and we just got enough time to get you to the airport." My wife, she was on the porch with the baby in her arms and everything. I said, "I don’t have time to even shower." He said, "You got to do all that there." So he ran his hand in his pocket and gave me ten $100 bills, a thousand dollars. He says, "Buy somethin’ to wear out there. Your record’s number one, you’re playin’ the Twenty Grand with Marvin Gaye." So they whizzed me to the airport, I got on the plane, dirty as a pig, they must’ve thought I was nuts or somethin’, but that’s just how quick it happened. And I went out there and MGM, that’s the parent company to Verve, they had some national promotion there with the Limousine, right at the airport, and as soon as I got in the Limousine, the disc jockey, whoever was on, I can’t recall the name now, says, "And now the number one record in Detroit." And here it comes [sings the intro], "Ain’t Nobody Home." Well, that was the greatest feeling that an artist can ever have! It was just unbelievable. But this the only business you can be poor as a Georgia turkey today and make a record, go to sleep and wake up a multi-millionaire. That’s how quick it can happen.

Well, I guess now you know the session musicians on that album are pretty much legends.

Yes they are. We had great musicians. Paul [Griffin] on the piano and Eric Gale on the guitar, they’re legendary, I’ll tell ya, and I attribute that to Jerry’s great ability to handpick musicians and, by the way, we recorded live. When we recorded all those songs, we were always right there, we didn’t punch anything in. I was singin’, they were playin’ and that’s how we recorded. And that’s how we got those great feels on those songs because it was as though we were doin’ a live show. Some producers, they’ll punch the vocal in later, they’ll do the horns later. We never did it that way. We did it all right there, and that’s how we got that great feel. Those musicians, they were the greatest.

Where did "Get It While You Can" get to? Did that do well?

Yes, very well. And, of course, when Janis Joplin did it, it just put icin’ on the cake! A major superstar like that to do my record, my music. I was so honored to have her do it. When we made that record in the studio, we knew that song was… we was makin’ a serious statement with that song because it showed the versatility of Howard Tate. A lot of artists, they can sing one style, but I’m blessed with a gift, I can sing any style. I can sing the blues, I can come back and sing a "Get It While You Can," I can come back and sing a funk song in the order of Wilson Pickett or James Brown, I can do it all.

Now, was the next album the one you did for Turntable Records and you did that in Jamaica?

Yes. They recorded the tracks in Jamaica. Really, that album was done by the Coasters, but they wasn’t satisfied with the rendition the Coasters did on the songs. So they asked me would I try to do "These Are the Things That Make Me Know You’re Gone" and "That’s What Happens When You Leave Me Baby." They wanted to hear how I sounded on it. Well, they were so impressed they said, "You gotta do the whole album." So I did that whole album, but originally those songs were written for the Coasters.

So they just sent you the tracks and you recorded it here?

They had the tracks, they brought ’em over from Jamaica and I recorded ’em in New York.

Then you went back with Ragovoy and went to Atlantic.

I felt as though Jerry, one thing he could do and that is write for Howard Tate. He felt Howard Tate. He dreamed, he slept, he ate Howard Tate. There’s something about my style and his ability to produce and arrange that went hand in glove. In fact, we’re doin’ an album now that’s gonna completely rock the music world when it’s released. It is so sensational that I can’t find words to depict to you how sensational it is. We’ve been doin’ a couple of the songs on the shows we’re doin’. One is called "Sorry, Wrong Number," and the other one’s "Mama Was Right."

One song on the Atlantic album that I was tempted to shout out for at the show was "Girl From the North Country."

"Girl From the North Country." Great song. I enjoyed doing that song so much and I kind of wanted to do that song in New York, but I knew Atlantic was gettin’ ready to release this CD again. It’s comin’ out, you know, next week. And I’m gonna be doin’ it on the new show when I go around on the new tour. "Girl of the North Country Fair," and also the Band’s "Jemima Surrender." We’re gonna be doin’ all of those. Great song by Bob Dylan, "Girl of the North Country Fair."

So then what happened?

Well, the only problem I had with Atlantic and with Verve back then was getting’ paid. We did fine with everything, but then when it came time to get paid, you could never get paid. So that was the problem I had. And that disgusted me at the time and, of course, I left Ragovoy, I left Atlantic and I just said, the heck with it. You know, if they’re not gonna pay me, then I just won’t record. And I imagine a lot of artists do that. It wasn’t just me. Most artists. When you look at Motown, the only artists got paid there was Smokey Robinson, and I do believe that’s because he was married to Berry’s sister. And Diana Ross, and I believe that’s because she had his child. But the others didn’t get paid. It was a thing of that day. Of course, today’s a different day, and that’s why I decided to come back and do another CD and do some more albums to sort of leave a legacy here that will be remembered till the end of time.

During the last 30 years or so, did you have any idea that there were people interested at all in your music?

No, I didn’t. I knew there was underground interest in me years ago. I knew that. But they kept me booked on the chitlin’ circuit, and I’ll say it that way because that’s what it really is, that’s what they call it. I was on all the one-nighters down through Mississippi, Tennessee, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Oklahoma, Texas. I worked 360 days a year for 20 years! And they kept me on those. And the underground, they always tried to book me, especially overseas. But the agency I was with, Universal, they kept me on those tours, all the time. It comes from not having good management. I should never have been on those tours. I should’ve been playing the underground circuit where most of my fans are today, all over the world, and that’s where my music is really appreciated and loved. I knew there was interest. They tried to book me in England so many times. And I’d never go because I got comfortable doin’ the Southern tours, and that’s where it was at. And what do the booking agencies care?

I remember hearin’ your record and playing it for friends, and I knew you were from Philly. And I would try and look you up in the Philly phone book, and I had other friends who talked to the Dixie Hummingbirds, and nobody knew.

Ira Tucker wanted me to do some of his songs, "Love Me Like A Rock." You remember that? They made that. Well, he gave me that song to do. And I didn’t do the song. I got so disgusted with the music business until I just sort of dropped out and nobody knew really where to find me because I got heavily involved with the church. And they wasn’t lookin’ in the right places or they could’ve found me very easily.

When did you get involved with the church?

I really got involved with the church heavy in 1994. That’s when I really, really got involved with the church. But the church has always been a part of my life. My roots come from the church.

Would you at some point like to do a gospel record?

Yes, we plan to do one. I was talking with Jerry about doing a couple of gospel songs or one gospel song on this CD. I’m writin’ and I got a couple of ideas. They’re not finalized yet, but definitely so. Because God is first in my life, and that’s the thing that even singin’ secular music, you know, I hope to draw people to Christ by the life that I live. The way I carry myself, the way I walk, the way I talk, the way I act and, you know, show a lot of love. That’s why I have no problem singin’ love songs because God is love.

Are you using the Uptown Horns everywhere?

We’re looking into them being my band. We are negotiating that at this very moment. Jerry is very involved in negotiating that because we want to take them overseas with us. We want that Howard Tate sound. The public deserves it, and we don’t wanna go into towns with one band here and one band there. We want to have that sound to really please the people. They’re such a great audience, and they deserve the best. And we wanna give it to them. And we feel the Uptown Horns is a great band. They’ve been my fans, and they know my music. They’ve played it. And we feel that me and the Uptown Horns, they fit, like hand and glove.

The thing I liked about the show was you didn’t really try to change anything; you left the songs the way they were when you cut them.

Well, that’s what I tried to do because the fans, they know the songs, they know every word. They’ve lived those songs and that music all these years, and I felt as though it was deserving to keep ’em just like they were. So when they look back and remember they saw Howard Tate, they’ll say, "It was just like the record."

In recording the new album, are you trying for the live sound or are you doing the modern thing, recording tracks?

No, no, we’re going for the live sound. That was one thing Jerry said, "No way. We’re doing the live thing with the live musicians. We want our public to get the best they deserve. We don’t want horns from a synthesizer and all that. We want the live horns.

Is this an exciting time for you now?

Very much so. I love it. I’m really pumped up and excited. I’m ready to go, you know. I find that I’m almost like a fighter who’s training for a fight to reach his peak, and I find I’m beginnin’ to get up that way. I realize my fans, how great they are, they bought my music all these years. And they appreciate it so much. And the least I can do is give ’em a dynamite show and record some more great music for ’em. And I’m so blessed to have Jerry with me. We’re together again and you know, of course, he’s the greatest producer and writer in the world today (laughs). I know Quincy Jones is good, but I’ll take Jerry Ragovoy.

One of the sweetest voices in soul music, combined with one of the most savvy soul producers—Howard Tate & Jerry Ragavoy—and God has seen fit to reincarnate them! Is this a beautiful country or what?

—Al Kooper

|