In October, scores of musicians performed on the stage of Madison Square Garden as part of a massive charity concert to aid the families of those who perished in the recent terrorist attacks. Former Beatle Paul McCartney was the prime organizer of the quickly thrown-together benefit concert—an interesting parallel, because it was another former Beatle, George Harrison, who organized the grandfather of all rock benefits at the same venue, thirty years earlier. The Concert for Bangladesh, held in August 1971, was also thrown together in a hurry, and many of rock's towering figures came to perform for a charitable cause, at Harrison's request. The result was not only a truly historic concert, but also a damn good show. Thirty years later, the benefit concert is a common occurrence, and it was George Harrison who got the ball rolling. Harrison succumbed to cancer on Novermber 29, and it is only fitting that we take a look back at one of his finest hours. Let us begin with a brief chronicle of the events that led to him to organize the concert.

In October, scores of musicians performed on the stage of Madison Square Garden as part of a massive charity concert to aid the families of those who perished in the recent terrorist attacks. Former Beatle Paul McCartney was the prime organizer of the quickly thrown-together benefit concert—an interesting parallel, because it was another former Beatle, George Harrison, who organized the grandfather of all rock benefits at the same venue, thirty years earlier. The Concert for Bangladesh, held in August 1971, was also thrown together in a hurry, and many of rock's towering figures came to perform for a charitable cause, at Harrison's request. The result was not only a truly historic concert, but also a damn good show. Thirty years later, the benefit concert is a common occurrence, and it was George Harrison who got the ball rolling. Harrison succumbed to cancer on Novermber 29, and it is only fitting that we take a look back at one of his finest hours. Let us begin with a brief chronicle of the events that led to him to organize the concert.

As with the Concert for New York, the backdrop to the Concert for Bangladesh involved massive human suffering and death, and massive amounts of money needed to be raised for relief efforts. Unlike with New York, however, the Bangladesh events did not directly affect most Americans, and part of the concert's purpose was to raise awareness of the problem. A combination of civil war, a reign of terror, intense flooding and poverty, and disease had ravaged the people of East Pakistan, with hundreds of thousands dying, and millions more seeking refuge in neighboring India. Master sitar player Ravi Shankar, who was a native of East India, heard of the reports and wanted to raise money in order to aid his suffering countrymen. Initially, Shankar had asked George Harrison and actor Peter Sellers to MC an Indian music concert, which was expected to raise around $20,000 for the Bangladeshi people. Harrison, coming off a hugely successful release with his album All Things Must Pass (and still looked upon by the world as "Beatle George, Rock Royalty"), and Shankar quickly recognized that far more money could be raised by a rock concert, and Harrison immediately set about organizing in a few weeks what logistically should have taken months.

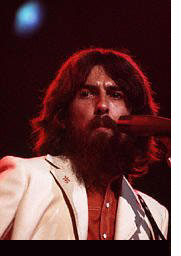

Upon reflection, it is amazing that the line-up came together as it did. Harrison put out calls to marquee-name friends like Eric Clapton, Bob Dylan, Ringo Starr, Leon Russell, Billy Preston—and the bandmates he had acrimoniously split from only a year and a half earlier, John Lennon and Paul McCartney. Starr agreed to perform, while McCartney declined, feeling that appearing in concert with Harrison, Lennon, and Starr would only heighten the public cries for a Beatles reunion. John Lennon initially offered his support, but within days, he pulled out and left the country, upset that Yoko Ono was not invited to participate. Bob Dylan, who had been keeping a low public profile for the previous two years, waffled on his commitment until the very moment he walked out on stage. Eric Clapton was another problem. The famed guitarist, whose last project was the Derek and the Dominoes tour, was at the beginning of a three-year period of inactivity, brought about by depression and heroin addiction. In addition, Harrison himself had never headlined a concert under his own name, and the guitarist had his own jitters to overcome. Despite all these uncertainties, on August 1, 1971, the former Fab walked onto the stage of the Garden, sporting long hair and a long beard, and announced to the cheering crowd, "I'd just like to say, before we start off with the concert, to thank you all for coming here. As you all know, it's a special benefit concert. We've got a good show lined up for you—I hope so, anyway..." The events leading up to the concert having been established, we now shift our emphasis to an analysis of the performance itself. It must be recognized, of course, that aside from being the first all-star rock benefit, the Concert for Bangladesh contains some truly wonderful music. The film and album of the event are a testament to that. The music that was recorded has a sustained undercurrent of passion and professionalism that many subsequent rock benefits have lacked. The line-up for the event included Ringo Starr and session drummer Jim Keltner on the drums, Leon Russell on the piano, and Billy Preston, who played the electric piano solo on "Get Back," on the organ. On guitars were former Taj Mahal band member Jesse Ed Davis, Eric Clapton, and Harrison himself. On bass was Carl Radle, who played with Derek and the Dominoes, and Klaus Voormann, who played bass on the early John Lennon and George Harrison solo records. Rounding out the band was the band Badfinger, the Hollywood Horns, and several backup singers.

Ravi Shankar opens the film and record with a twenty minute Indian music set, playing with several Indian musicians. After the Indian music section, Harrison and friends kick off the rock music section with a high-energy version of "Wah-Wah," a song off of All Things Must Pass that Harrison wrote about Paul McCartney during the tension-filled Let It Be sessions with the Beatles. "Wah Wah/You've given me a wah wah/ And I'm thinking 'bout you/All the things that we used to do" sings Harrison, as Starr and Keltner hammer out a steady beat, and the horns blare in the background. The melodic rocker, one of Harrison's best, chugs along, with the large ensemble sounding as if they'd been playing together for months, not days. As the song ends, Harrison, dressed in a white suit with an orange shirt, turns in his electric guitar for an acoustic, and leads the band through his monster-sized hit, "My Sweet Lord." The song, which features exquisite slide guitar work by Clapton, and lyrics that read "I really want to see you/I really want to be with you/I really want to see you Lord, but it takes so long, my Lord," was all over the airwaves in the summer of 1971, and there is none of the controversy which would eventually surround it (Harrison was tangled up in a lawsuit throughout the mid-1970s over plagiarizing the Chiffons' "He's So Fine.") Yet another song from All Things Must Pass, which provided the bulk of Harrison's material for the event, is next, the funky-yet-spiritual "Awaiting On You All." The song is the only one in Harrison's entire catalogue that has an almost Motown sound to it, and after finishing the number, Harrison announces, "I'd like to continue with a song from a member of the band, old friend of mine, Billy Preston."

Preston injects a good deal of spirit into the precedings, playing his minor hit "That's the Way God Planned It" (in perfect keeping with the spiritual tone of the previous song), and getting up and dancing at the front of the stage like a wildman during the fast-paced instrumental-boogie ending. From Preston, the spotlight moves over to Starr, who sings his recent hit, "It Don't Come Easy." The original studio recording, featuring Clapton, Harrison, Starr, and Stephen Stills, was stiff and lifeless, but in concert, it is a fast-paced rocker that easily outdistances anything Ringo had sung in a Beatles show. There is a marvelous moment on the film showing Ringo flubbing his last line ("Nah-naaaaaah-na na, and it's growing all the time, and you know it don't come easy"), flashing a grin to Keltner, and receiving a warm round of applause. Harrison steps back to the microphone for "Beware of Darkness," a slow, haunting song that he duets with Leon Russell on. At the song's conclusion, Harrison extends his thanks to the musicians for their services, and calls out the names of each band member. After receiving the biggest round of applause during the band introductions, it is Eric Clapton's chance to shine. Although he does not sing a note during the concert, the next song is "While My guitar Gently Weeps," off of the White Album. Clapton played the guitar solo on the studio version, and now in concert, he and Harrison trade licks back and forth in an extended version. For many in attendance that night, just seeing George Harrison and Eric Clapton playing together at the height of their powers was thrilling enough, and now, thirty years later, the sight of the two musicians playing off each other takes on added poignancy.

The most dynamic section of the concert comes with Leon Russell's medley of the Rolling Stones' "Jumpin’ Jack Flash" and the Coasters' "Youngblood." Rearranged slightly for the piano and guitar set-up, the song features a high energy Russell whooping and hollering "Well it's aaaawwwwlll riiiiiight, now/ In fact it's a gas," giving screams of encouragement and joy to the other players, and pounding the hell out of his piano. Just as the song seems to be reaching a fever pitch, Russell slows things down and goes into a Peter Wolf-like boogie-rap, leading into a beautiful version of "Youngblood," and then taking the band back into the exciting closing of "Jack Flash." After an ecstatic reception from the audience, the energy level is taken down a notch as Harrison steps out to play an all acoustic version of "Here Comes the Sun," the first time he has played a Beatles song on a proper stage since 1966. As big a deal as that may have seemed to the crowd, when Harrison steps to the mic to say "I'd like to introduce a friend of us all—Mr. Bob Dylan," the speakers of the stereo nearly blow out due to the thunderous applause. Dylan's name was never circulated as one of the

musicians on the bill, and his appearance on stage that night came as a

surprise to most people (and, indeed, possibly to some of the musicians).

That Dylan pulled through for Harrison, after being almost completely absent

from the concert circuit for five years, makes this event truly memorable.

Keeping in tune with the social-awareness of the evening, Dylan opens with

"A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall," and goes on to play such treasures as "It Takes

a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry," "Blowin' in the Wind," "Mr.

Tambourine Man," and a stunning version of "Just Like a Woman" which

features Russell and Harrison on backing vocals. These were the days when

Dylan was still seen by many of his generation as an almost prophetic

figure, his singing voice was still strong and coherent (although one must

stop short of ever calling his singing voice "good"), and his mere presence

adds a weight and a cultural importance to an already momentous concert.

Dylan leaves the stage at the conclusion of "Just Like a Woman," and

Harrison then leads the group through a version of "Something," the first

time he ever performed the two-year-old classic live. The final song of the

evening was penned specifically for the event. "Bangla Desh," a lightweight

tune, nevertheless puts forth the message of the importance of the event

and of helping those suffering people who are so far away. As the number

heads towards a close, Harrison takes off his guitar, waves to the crowd,

and leaves the stage to thunderous applause while his bandmates continue to

pump away. The film and the record of the event end with a sound which the

people on that stage were all too accustomed to hearing—a thrilled

audience.

The most dynamic section of the concert comes with Leon Russell's medley of the Rolling Stones' "Jumpin’ Jack Flash" and the Coasters' "Youngblood." Rearranged slightly for the piano and guitar set-up, the song features a high energy Russell whooping and hollering "Well it's aaaawwwwlll riiiiiight, now/ In fact it's a gas," giving screams of encouragement and joy to the other players, and pounding the hell out of his piano. Just as the song seems to be reaching a fever pitch, Russell slows things down and goes into a Peter Wolf-like boogie-rap, leading into a beautiful version of "Youngblood," and then taking the band back into the exciting closing of "Jack Flash." After an ecstatic reception from the audience, the energy level is taken down a notch as Harrison steps out to play an all acoustic version of "Here Comes the Sun," the first time he has played a Beatles song on a proper stage since 1966. As big a deal as that may have seemed to the crowd, when Harrison steps to the mic to say "I'd like to introduce a friend of us all—Mr. Bob Dylan," the speakers of the stereo nearly blow out due to the thunderous applause. Dylan's name was never circulated as one of the

musicians on the bill, and his appearance on stage that night came as a

surprise to most people (and, indeed, possibly to some of the musicians).

That Dylan pulled through for Harrison, after being almost completely absent

from the concert circuit for five years, makes this event truly memorable.

Keeping in tune with the social-awareness of the evening, Dylan opens with

"A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall," and goes on to play such treasures as "It Takes

a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry," "Blowin' in the Wind," "Mr.

Tambourine Man," and a stunning version of "Just Like a Woman" which

features Russell and Harrison on backing vocals. These were the days when

Dylan was still seen by many of his generation as an almost prophetic

figure, his singing voice was still strong and coherent (although one must

stop short of ever calling his singing voice "good"), and his mere presence

adds a weight and a cultural importance to an already momentous concert.

Dylan leaves the stage at the conclusion of "Just Like a Woman," and

Harrison then leads the group through a version of "Something," the first

time he ever performed the two-year-old classic live. The final song of the

evening was penned specifically for the event. "Bangla Desh," a lightweight

tune, nevertheless puts forth the message of the importance of the event

and of helping those suffering people who are so far away. As the number

heads towards a close, Harrison takes off his guitar, waves to the crowd,

and leaves the stage to thunderous applause while his bandmates continue to

pump away. The film and the record of the event end with a sound which the

people on that stage were all too accustomed to hearing—a thrilled

audience.

In the past 30 years, massive rock charity concerts have become common. Live Aid, Farm Aid, the Concert for Kampuchea, Neil Young's charity shows, and the recent Concert for New York have all been used to great effect in raising money and awareness for various worthy causes. It was George Harrison, however, who gave them all the blueprint for how it should be done, and the music documented at the Concert for Bangladesh still stands as one of the finest performances of its time. Unlike the more recent charity events, this concert took place at a time when the musicians were all still young and at the top of their game, when idealism had not yet been tempered with cynicism, and when it still seemed possible for the power of good music to make magic happen. The Concert for Bangladesh is currently being remastered and ready for reissue in January, and while the great organizer of the event, George Harrison, is sadly no longer with us, his social consciousness and his timeless music endure.