I recently found myself in one of those arguments that I’m convinced every book-reading or movie-viewing American has at one point been involved in: arguing the merits of Twilight. And it got me thinking about Bella’s bed—in the fifth and final movie her and Edward retreat to their cabin cottage and end up next to a big, designer-chic bed, a bed which explicitly and cringingly is meant for one thing and one thing only—and seeing this piece of furniture got me wondering about love and marriage, but not for the reasons you’re maybe thinking. Let me explain.

The Twilight Argument happened with a group of friends at a bar, discussing literature because sometimes literature is what I have in common with people. The topic of Twilight came up, as it somehow inevitably does. Full disclosure: I’ve read all four books at least twice, and seen the movies countless times. I feel your judgment. Judge. Get it over with. Feel the waves radiate like an army of Slinkys. You are a child of the universe. Now, let’s move on.

I don’t love Twilight, but I also don’t love the typical arguments made against the series. We’re all writers, here. To call the novels low brow or cliché or redundant or sentimental would all be accurate arguments, but it would also be missing a lesson—they are a series of books which have captivated millions of people domestically and abroad. Every writer’s goal should be significant innovation, yet captivation as well. We learn innovation from Wallace, DeLillo, Austen, St. Augustine. We learn mass market appeal from King, Collins, Meyer, Doctor Phil, The Walking Dead, Procter and Gamble.

I see those red flags you’re waving—don’t worry, I’ll qualify. I don’t consider the Twilight series art, and I don’t see it as beneficial literature. It is escapism at best, and I imagine the statistics on how often eye imagery appears in the first book will be a footnote in future encyclopedias under death of literature. But to call the books plain old bad is reductive. My only point is that there is something to be learned from the mass amounts of people they’ve reached. I love to argue this—those books are entertaining to a whole lot of people, including yours truly.

Something has happened to the desire to entertain. The biggest mistake an artist can make—a mistake I’ve made hundreds of times before, likely one I’ll make countless times again—is assuming that their art is inherently interesting. I think I‘ve just accidentally called myself an artist. Once on the train I overheard a man call himself the most humble person in the world.

Say what you will about Meyer, but she never spent a page describing how the wing of an airplane looked in the moonlight—she never possessed the burden of well-crafted language. She’s never presumed her reader hasn’t just put her book down to fix a sandwich. She’s never presumed her work is inherently interesting, because it isn’t. She fights for it. She needs you to turn the page. We live and write in that world now, a world where people make sandwiches, where they don’t need books. Nowadays, a reader is doing a book a favor by reading, rather than the other way around.

The other night, I was waiting in the underground for Chicago’s blue line, and a man was standing near me, yelling his poetry as loud as he could. Never before has poetry only echoed on a literal level.

Art is a forceful medium of expression. It takes up a consumer’s time and headspace. Read this. Listen to this. Look at this. Appreciate it. Love it. Want it, need it. The imperative is doubled if the consumer has spent money, introducing a debt to the exchange of meaning. The impetus more than ever has been on the artist to pack, fill and delight. Writers like myself, those in the lit-mag game and attempting to bust out, should always be asking: will the reader need to turn the page? I can’t help but make overly melodramatic comparisons: sometimes when I think about Stephanie Meyer, I picture her as Russell Crowe, gladiator-clad, yelling at the coliseum: Are you not entertained?!

I was making a point. My only point is that there’s something to be learned, no matter how often you cringe from bar-bantering about Meyer’s writing. Cringe all you want, the words on the page won’t change. They’re kinda cringy books. I’m only saying there’s a lesson to be learned.

I’m only describing an argument I had with my friend.

We traded typical literary language and made our obscure comparisons and used ethos-dropping words like prolepsis. We all drank craft beers and competed to come up with the best one sentence short story. Mine, which was not the best, was: Demand the equestrian police, we’ve burnt the script.

My friend gave the usual stump speech, with which I did not and could not disagree: the themes of Twilight are anti-women. A woman has to control her primitive sexual urges or die. Sex before marriage will kill you. Sex without changing to suit your partner will kill you. A woman has to give up her family to be with the person she loves. Morals from the days of Spanish influenza are more moral than modern morals. It goes on. He argued it more eloquently. My representation is a brutal diegesis; hey, smart words for the sake of smart words. Other writers have argued more and most eloquently. We know the list, we agree with the list.

I couldn’t argue with my friend. He was right, completely and absolutely. Yet the books have been purchased (ugh, capitalism, right?) by millions of people, people thirsty for pathos. Look at the books conceptually, structurally, the plot and narrative satisfactions. I’m on no bandwagon, but just look at it—look.

I’m wary of mass opinion and sudden stigma. Everyone loves Target, but hates Wal-Mart. Everyone loves Lena Dunham, but hates Marie Calloway. Am I missing something here? These generalities aren’t entirely true, probably aren’t even generally true, but we see how the over-publication of every waking thought (I think I want a turkey sandwich for lunch, today. What do you guys think?) in the age of social media can lead to perhaps too-hasty dismissals in the file cabinet under M, for manipulative.

I’m not saying I’m not part of the problem. Who am I to be writing about Twilight? Exactly! Who am I to be writing about writing, as if I’ve eaten the whole wheel of cheese? Ask that question after every sentence. Disagree with me—I’ll say, “well, I’ve certainly been wrong before,” because that’s what I say when faced with my own polar wrongness, never actually admitting it.

In terms of plot, Twilight isn’t White Noise. In terms of satisfactions, it isn’t Junot Diaz or George Saunders. We can namedrop all day. Yet, still. I like to think that I’ve learned something from the Twilight books—something about craft, about reader wants and expectations, about narrative simplicity, about words and how they can be packaged. There is something to be learned about literature even from books that maybe don’t deserve that capital-L-title—perhaps how to understand mass-perceived depth to achieve empirical depth.

I don’t think I’m convincing anyone. That’s cool. That’s not the point of all this. The point is there’s a new problem with Twilight (gasp!)—one that everybody who’s ever been in a relationship has completely saw coming. Let’s talk about the movies now, specifically, the fifth and final of the series.

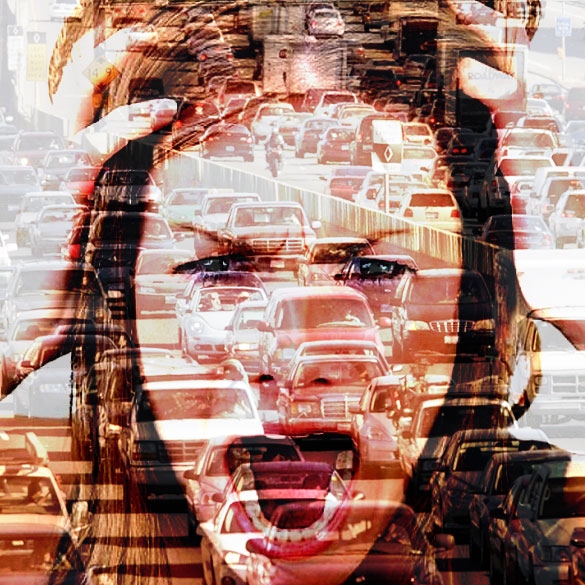

The problem I have with Breaking Dawn-Part 2 is that Edward and Bella’s love is a total not-credible fiction, and is showing the next generation of humans an inaccurate representation of love and how it really looks to be committed, lifelong, to another person. Sure, I’m twenty four. What do I know about lifelong commitments? But I know what they’re not. I’m not saying every movie needs to be brutal realism like Blue Valentine. But can’t we enjoy our popcorn and Twizzlers (a delicious combination, if you’ve never tried them together) in some type of happy medium?I buy into the fablistic and fairy tale elements of the vampire story, and I buy into the fact that Edward and Bella really do, truly and somewhat inexplicably, love one another forever—but actual ‘love,’ whatever that word means, isn’t just handholding and how-cute smiles and terribly uncomfortable sex scenes.

Hasn’t love as a concept been assaulted enough? Do we allow filmmakers to continually rely on the automatic pathos of ‘love’ without qualification? The word is meant to have gravity. That sentence is the most important in this whole essay, so I’m going to repeat it. The word is meant to have gravity.

Edward and Bella never fight. They never argue. They never disagree. They never have anything but gold fawning love eyes for their perfect other, for, ev, er. They never look at one another. I think the only thing they have in common is the fact that they love each other, and now vampirism. Their relationship is that of a ten year old circling yes on the note she received from the my-mom-says-I’m-handsomest boy in class.

The movie is a continuation of the Disney model which taught my generation and those previous that you’ll never be happy alone, that loving relationships never end, that that mysterious girl with the dark hair who smells so damn delicious after walking past a table fan will be the last person you ever want for the rest of existence.

More, it teaches America’s youth not just bent ideologies about marriage and sex and womanhood, but that when you find that person you want to spend the rest of your life with, everything will be blissful and perfect and you’ll go live in a perfectly decorated cabin in the woods and have an incredibly cute child who cries so rarely and only for well-timed cinematic effect.

Does Bella ever get tired of buying new beds? This is my example. One thing all five movies have made perfectly clear is the fact that vampiric sex is messy. Things get broken. E and B’s ambitious plan is to spend the rest of eternity having bed-breaking love with one another—we never sleep, we never get tired, we never run out of breathe. We can do this forever. Sure, they never sleep, and sure, money is no object for the Cullens, but still—furniture is the worst. I don’t think I’ve ever lifted something over ten pounds in my entire life without getting at least a little bit mad. Wouldn’t she get tired of having to buy new beds? Or if Edward bought the beds, would she get frustrated by his masculine tastes? Or by his feminine tastes? After a month, a year, one hundred years of breaking beds with their marital bliss? I see so many permutations for arguments revolving around this one pivot point. In the world of Twilight, I don’t see them arguing about beds. It would be too real, too human.

—

Jake Wrenn is a writer in Chicago.