“We’re not computers, Sebastian. We’re physical.”—Roy Batty

Thirty years ago right around this time, Ridley Scott was wrapping up production on his film Blade Runner. By the summer of 1982, it had opened in over 1,200 theaters across the country. Routinely panned and even attacked by test audiences, the film fared little better in theaters. In fact, it was a certified box office flop. Virtually no one, it seems, liked Blade Runner. Fortunately, in the three decades since it first debuted on the big screen, viewers discovering the film on cable TV and DVD have come to appreciate it as not only a cult film par excellence but an emotionally challenging, thematically complex work whose ideas and subtexts are just as startling as its now famous production designs.

Set in Los Angeles in the year 2019, Blade Runner depicts a world where the sun no longer shines. Instead, a constant rainy drizzle adds to the dark character of this futuristic landscape. Although the opening shot’s aerial perspective suggests a modern Los Angeles, the audience soon discovers a very different city in which the endless archipelago of suburbs have been replaced by a dark and ominous landscape lit only by occasional flare-ups of burning gas at oil refineries. An energy shortage has crippled life in the future. The earth is decayed, and millions of people have been forced to colonize other planets. Those who remain behind live in huge cities consisting of a conglomeration of new buildings four hundred stories high and the dilapidated remains of earlier times.

The streets teem with Asians, Hare Krishnas and men in fezzes, all lit by a lurid blaze of flashing neon. The crunch and crush of modern population seems overwhelming and totally dehumanizing. Genetic engineering has become one of the earth’s major industries, with humans now assuming the role of “maker” and “creator.” Since most of the world’s animals have become extinct, genetic engineers now produce artificial animals. And artificial humans called “replicants” have been created to do the difficult, hazardous and often tedious work necessary in the colonies on other planets.

If Michelangelo were alive in Ridley Scott’s future world, rather than portraying God on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, he would likely paint the human creators of the Tyrell Corporation, the world’s leading manufacturer of replicants which has just introduced the “Nexus-6,” a replicant with far greater strength and intelligence than human beings. These latest-model replicants represent an obvious potential danger to human society, and their introduction on Earth—an offense calling for the death penalty—has been strictly outlawed. When the replicants somehow make their way back to Earth, they are systematically “retired” (but not “killed” since they are inhuman) by special detectives or “Blade Runners” trained to track down and liquidate the infiltrators.

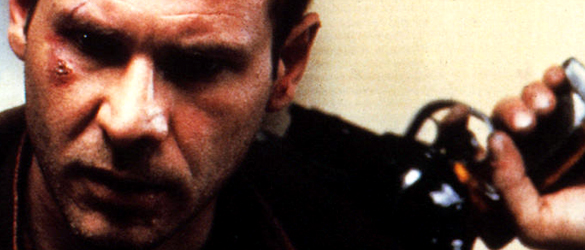

Police receive an emergency report that four “combat model” Nexus-6 replicants—two male and two female—have killed the crew of a space shuttle and returned to Earth. The Blade Runner assigned to track them down and “terminate” them is Deckard (Harrison Ford, in his best performance).

The film shifts dramatically when the replicants, who are on a mission to extend their short life span, display a stronger sense of community than the human beings on Earth. With his three partners now destroyed by explosive bullets, the silver-blonde replicant Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer) succeeds in finding his way to Tyrell himself, the master of the Tyrell Corporation and the genetic engineering genius who actually designed him. Batty wants to have his genetic code altered to extend his assigned four-year life span. He simply wants to live. But when he discovers he cannot, Batty kills Tyrell in a despairing rage, calling him (as Zeus to Cronos) “Father.” At one point, Batty remarks: “It’s a hard thing to meet your maker.”

Blade Runner cannot be understood without comprehending the deeply felt moral, philosophical, ecological and sociological concerns that are interwoven throughout the story. Three key, yet profound, questions contribute to the core of Blade Runner: Who am I? Why am I here? What does it mean to be human? Thus, the eternal problems in the film are essentially moral ones—that is, should replicants kill to gain more life? Should Deckard kill replicants simply because they want to exist?

Defining what it means to be human, however, provides most of Blade Runner’s philosophical focus. This is increasingly the dilemma faced by contemporary society—that is, the most vital question confronting us is how to maintain our humanity in the face of overwhelming technologies that tend to dehumanize us.

Philip K. Dick promulgated a “sheep” metaphor in his novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968), upon which the film is based. “Sheep stemmed from my basic interest in the problem of differentiating the authentic human being from the reflexive machine, which I call an android. In my mind android is a metaphor for people who are psychologically human but behaving in a nonhuman way.” During research for an earlier work, Dick had discovered diaries by Nazi SS men stationed in Poland. One sentence in particular had a profound effect on him. That sentence read, “We are kept awake at night by the cries of starving children.” As Dick explained, “There is obviously something wrong with the man who wrote that. I later realized that, with the Nazis, what we were essentially dealing with was a defective group mind, a mind so emotionally defective that the word ‘human’ could not be applied to them.” More importantly for us, Dick observed, “I felt that this was not necessarily a sole German trait. This deficiency had been exported into the world after World War II and could be picked up by people anywhere, at any time.”

The dilemma is even more acute than when Dick was penning Sheep, for we have moved deeper into the methodological terrain of a new world—one more than ever dominated by what we believe to be the machine. As a consequence, we have reconstructed the self in the face of the dissolution of the ontological structures that have heretofore provided a validation of being. In the wake of this dissolution, as Scott Bukatman writes in Terminal Identity, we “humans” have arrived at “a new subjectivity constructed at the computer station or television screen.”

In the case of the replicants in Blade Runner, the so-called fusion of machine preciseness is meshed with the matrix of human flesh—but supposedly without the human characteristics of emotions, empathy and so forth. Deckard, who had been indoctrinated into believing that replicants were mere machines, was facing an emotional dilemma because of a stirring of regret (or empathy) when “retiring” the replicant/machines. As we find out in the later 1992 director’s cut of Blade Runner, this could be that Deckard, possibly a replicant himself, intuitively identified with them. Or was it simply his humanity emerging from the closet of decayed urbanity that engulfed him?

The central problems in Blade Runner are essentially moral ones. As producer Michael Deeley points out, “Should the replicants kill to gain moral life? Should Harrison Ford be killing them simply because they want to exist? These questions begin to tangle up Deckard’s thinking…especially when he becomes involved with a female replicant himself.”

Blade Runner postulates the theorem that what has feelings is human. Thus, Blade Runner is as much about Deckard’s recovery of empathetic response as it is about the replicants’ development of such a response. The irritated Nazis kept awake by the children’s cries with their inability to empathize were less than human. “What raises the android Roy Batty to human status in Blade Runner,” writes Norman Spinard in Science Fiction in the Real World, “is that, on the brink of his own death, he is able to empathize with Deckard. What makes true beings is that ultimately, on one level or another, whatever reality mazes they may be caught in, they realize that the true base reality is not absolute or perceptual, but moral and empathetic.”

The ultimate relevance of Blade Runner lies in its challenge of what it must mean to be human. It raises the eternal gnawing doubt as to our own humanity or lack of it. These are the same issues raised by the great religions and philosophies of the past. And it speaks to how we respond to the pain of those around us. Do we reach for the one downed by the crushing perplexity of modernity or do we merely pass by, forgetting about that grizzled human lying on the sidewalk who is drowning in the gutter created by the disintegrating and dehumanizing post-modern existence?

—-

Please visit https://www.rutherford.org/multimedia/on_target/ to view Whitehead’s weekly video commentaries.

About John W. Whitehead: Constitutional attorney and author John W. Whitehead is founder and president of The Rutherford Institute and editor of GadflyOnline.com. His new book The Freedom Wars (TRI Press) is available online at www.amazon.com. Whitehead can be contacted at johnw@rutherford.org. Information about The Rutherford Institute is available at www.rutherford.org.

The one line that has always stuck with me after reading the book is that when we are long gone, all that would remain is garbage, but the pieces to me left behind speak of identity. And that is what Blade Runner is, the hunt to discover oneself, a brilliant masterpiece that fits perfectly with Sci-Fi movies such as The Thirteenth Floor, Imposter and Final Cut.