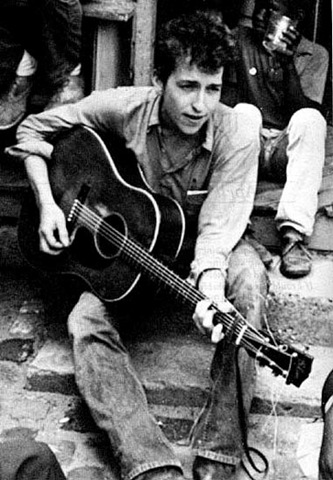

In March 1966, music critic Robert Shelton became privy to one of Bob Dylan’s allegedly best-kept secrets. “I kicked a heroin habit in New York City. I got very, very strung out for a while, I mean really, very strung out. And I kicked the habit. I had about a $25-a-day habit and I kicked it,” he said. Lately, many Americans were stunned to learn that the voice of the 1960s generation was at one point or another jockeyed by the mind-numbing drug, while others laid to rest their long-held presumptions of his heroin use. Still others are critical of the recent flurry over Dylan’s claim to a heroin addiction, for numerous reasons. Some point to the artist’s nearly pathological tendency to lie in past interviews. For instance, according to Rolling Stone Magazine’s Andy Greene, Dylan claimed to have worked as a prostitute during his time in New York in another 1966 interview with Robert Shelton. Other critics raise questions of Shelton’s moral integrity—why did he fail to mention this integral part of Dylan’s life in his biography, No Direction Home? Surprisingly, the question no one seems to be asking is, should this new insight change how Americans today look at Dylan’s life and work, and if so, how?

In March 1966, music critic Robert Shelton became privy to one of Bob Dylan’s allegedly best-kept secrets. “I kicked a heroin habit in New York City. I got very, very strung out for a while, I mean really, very strung out. And I kicked the habit. I had about a $25-a-day habit and I kicked it,” he said. Lately, many Americans were stunned to learn that the voice of the 1960s generation was at one point or another jockeyed by the mind-numbing drug, while others laid to rest their long-held presumptions of his heroin use. Still others are critical of the recent flurry over Dylan’s claim to a heroin addiction, for numerous reasons. Some point to the artist’s nearly pathological tendency to lie in past interviews. For instance, according to Rolling Stone Magazine’s Andy Greene, Dylan claimed to have worked as a prostitute during his time in New York in another 1966 interview with Robert Shelton. Other critics raise questions of Shelton’s moral integrity—why did he fail to mention this integral part of Dylan’s life in his biography, No Direction Home? Surprisingly, the question no one seems to be asking is, should this new insight change how Americans today look at Dylan’s life and work, and if so, how?

One of the most addictive drugs readily available on the street, heroin is more potent than its relatives, opium and morphine, and other than track marks, lacks the telltale signs of abuse that similarly addicting drugs leave in their wake, making it the drug of choice for many people who live their lives in the spotlight, such as Bob Dylan. This is how it works. When used, it shoots straight to the brain, and within forty seconds kills the body’s pain centers and releases a flood of dopamine which soaks the user in a transcendent euphoria that is warm, intense, and complete. It rapidly shuts down the brain’s frontal lobe, which analyzes the potential consequences of actions, as well as the limbic system, which controls emotion, motivation, and drive. The drug forms a habit after just one use, and the brains of repeated users eventually come to believe that the altered sense of reality heroin creates is the normal one.

It is not surprising that Dylan might have used heroin at some point in his career—it would put him in league with countless others in his field, such as Janis Joplin, Sid Vicious, and Miles Davis, to name a few. Unlike his peers, however, Dylan claimed the ability to compartmentalize his lyric-writing and his drug use. When asked in a 1969 interview with Rolling Stone Magazine’s Jann Wenner whether drugs influenced his songs, Dylan said, “No, not the writing of them; it just kept me up there to pump them out.” While this tale makes for a nice story, it is an unlikely one. A $25-a-day habit in the early 1960s averages out to an approximately $186-a-day habit today. If Dylan told the truth, he would be considered a hardcore user, who today spends between $150 and $200 a day just to keep up with their habit. If he really did have and kick a heroin habit this fixed, the ability to pigeonhole his work and his drug habit that he professes is simply ridiculous. A hardcore heroin habit would have indisputably affected his work, and to a careful observer, this shift in Dylan’s career may be readily apparent. So when precisely did he use heroin?

His eponymous March 1962 debut album featured only two original songs, both laced with lament. One of these songs was “Song to Woody,” an elegy which conflates his grief for the loss of his idol, the late Woody Guthrie, to a larger scale by bemoaning a world that “looks like it’s dyin’ and it’s hardly been born.” In just a few lines, Dylan’s lyrics give form and release to his anxiety, though without resolving the problem. Debatably, heroin had not yet usurped music as an outlet for his unease.

A year and two months later, he had undergone changes, but not so many so as to raise questions. He had legally changed his name to Bob Dylan, walked out of the Ed Sullivan Show, and released his sophomore album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. All originals, its thirteen tracks retained his previous album’s hillbilly twang and folksy charm, but beefed up his handwringing over personal and social problems. He was jaded, and far from numb. “You see, in time, with those old singers, music was a tool—a way to live more, a way to make themselves feel better at certain points. As for me, I can make myself feel better some times, but at other times, it’s still hard to go to sleep at night,” Dylan said of one song on the album. Perhaps it is this need to feel better that led him to experiment with heroin in the first place. Maybe music was not the escape from himself and others that he craved, agitating his disquiet rather than pacifying it. His third album, The Times They Are A-Changin’, further magnified his mushrooming concern with social issues such as racism, poverty, and the peace movement.

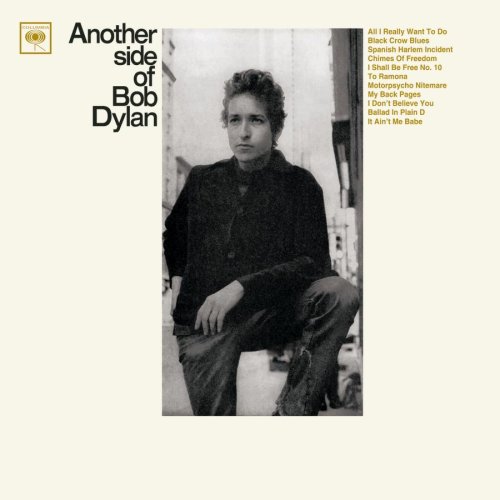

But it seems the times really changed in 1964 with the release of his fourth album, Another Side of Bob Dylan, whose strangely innocuous motif sticks out like a sore thumb among his earlier New York albums. Unlike his previous three albums, this album featured no accusatory songs—an unusual break in a trend of kvetching he had spent three years establishing. It displays a distinct lyrical dullness to issues at large in society at the time which coincides with original poetry by Dylan on the back of the album that is dimly aware of drug use in society, and possibly by Dylan himself. The back-cover poetry, besides featuring little drug-riddled phrases here and there, such as “junkie nurse,” “countless common housewives strung out on drugstore dope,” and “stoned galore,” makes metaphorical reference to a kind of drug that glazes over angst—arguably heroin. In one section, Dylan aligns himself with a “mob” which is hardly a mob at all, and which instead behaves like a group of foggy-headed, torpid heroin users.

But it seems the times really changed in 1964 with the release of his fourth album, Another Side of Bob Dylan, whose strangely innocuous motif sticks out like a sore thumb among his earlier New York albums. Unlike his previous three albums, this album featured no accusatory songs—an unusual break in a trend of kvetching he had spent three years establishing. It displays a distinct lyrical dullness to issues at large in society at the time which coincides with original poetry by Dylan on the back of the album that is dimly aware of drug use in society, and possibly by Dylan himself. The back-cover poetry, besides featuring little drug-riddled phrases here and there, such as “junkie nurse,” “countless common housewives strung out on drugstore dope,” and “stoned galore,” makes metaphorical reference to a kind of drug that glazes over angst—arguably heroin. In one section, Dylan aligns himself with a “mob” which is hardly a mob at all, and which instead behaves like a group of foggy-headed, torpid heroin users.

(a mob. each member knowin’

that they all know an’ see the same thing

they have the same thing in common.

can stare at each other in total blankness

they do not have t’ speak an’ not feel guilty

about havin’ nothing t’ say. everyday boredom

soaked by the temporary happiness

of that their search is finally over

for findin’ a way t’ communicate a leech cookout

giant cop out. all mobs i would think.

an’ i was in it an’ caught by the excitement of it),

he writes. Read conscientiously, “total blankness,” “temporary happiness,” and “leech cookout” instantly bring to mind images of a drug-induced daze, getting a fix, and pierced skin, all of the markers of heroin abuse. Like any user, Dylan was “caught by the excitement of it,” and found himself fully wrapped up in this passionless throng.

So is this the album that Dylan wrote while using heroin? If he did in fact abuse heroin for a spell in New York, Another Side of Bob Dylan may very well pinpoint when. At the least, the album hits the checkpoints. It was written during his New York years. Its lyrics are woozily anodyne, and its back-cover poetry is rife with drug imagery. And for argument’s sake, Another Side of Bob Dylan was the last album before Dylan’s electric period, the kind of style change that might accompany a lifestyle change, such as kicking a serious drug habit. However, just because Americans are reevaluating Dylan’s life does not mean they should or can do the same to his musical legacy. After all, it is still the same Bob Dylan. For many Bobheads, the discovery of a past heroin addiction will not disqualify him as “The Voice of the 1960s,” a title he assumed without contest years ago. As he said himself in 1963, “All I’m doing is saying what’s on my mind the best way I know how. And whatever else you say about me, everything I do and sing and write comes out of me.”