FEBRUARY 3, 1971, 11:07 P.M. It’s all a lie.

The New York City cop leans over the front seat, as the radio-car careens, screaming up Metropolitan Avenue in Brooklyn. He steadies the limp, bleeding body in the back. It’s been 25 minutes. The blood is black, jellied in the center, dried on the edges. It coats his beard, face, Army fatigue jacket. Still, the man in the back knows he must stay awake. He struggles. He clings to consciousness. If I fall asleep, I’ll die, he thinks. He hears the voice again. “It’s a lie. It’s all a lie.” The blood is thick in his nose and throat. He’s suffocating. He’s so tired. Stay awake, he tells himself. Keep your eyes open. Just keep your eyes open. The cop in the front says something, but the man in the back can’t hear over the sirens. He sees shadows in front and behind. The grotesque shapes seem to split and fall across his bloodied face. His eyes are heavy. Stay awake, he tells himself, again and again. Then, as if in one of those vaporous, just-before-waking dreams, the man in the back remembers: “Frank, why don’t you take the money? Just take it, Frank.”

FEBRUARY 3, 1971, 10:42 P.M. 778 Driggs Street, Brooklyn. Apartment 3-G. The emergency dispatcher gets a 1010 call from a civilian: investigate shots fired.

It seemed like a pretty routine heroin bust. Four cops from Brooklyn North get a tip that a drug deal is going down. So three officers—Gary Roteman, Arthur Cesare and Paul Halley—stay in a car out front. The fourth, Frank Serpico, watches from the roof. They’re waiting for the informant’s signal. Frank observes the buy in the hall outside apartment 3-G. When it’s over, he follows them out and motions to his partners. They jump out; one of the kids has two bags of heroin.

“Okay, let’s go in and get this Mambo,” says Gary. “How are we going to work this?” Frank asks. “Well, you make the buy. You get the door open for us. What the hell, you speak Spanish.”

Halley stays in the car with the kid with the heroin. The other three creep up the steps to the third-floor landing. Frank knocks, his other hand inside his jacket, cradling his .38. “Mambo….”

The door opens a few inches, the chain still on. Frank pushes; the chain snaps. It’s enough for him to wedge part of his body in. The guys on the other side are trying to push it closed. Frank needs help. He needs his partners, now! Nothing moves behind him. Instinctively, he turns. “What the fuck are you waiting for?” he hollers. His head and shoulders are in the alcove, inside 3-G. His mind races. Where are they? Nothing. The action takes fractions of a second; it seems like minutes. Frank turns his head back toward the opening into 3-G. Flashes of red, orange. Like searing shards of thin, jagged glass, the bullet penetrates his face. Officer down. But there’s no 1013 call—the highest priority dispatch that signals an officer is in trouble.

Frank hears nothing but the lingering echo of the blast. He’s alone. Blood pools and spurts from his head, staining the already sullied, white octangular tiles crimson. Not yet black and jellied, but flowing crimson. Crimson, the color of passion. Where is everybody, he wonders? Please, somebody? Lying flat, he listens. Nothing. Blood runs into his mouth. He’s numb. Number than silence. Is there anybody out there? Is there anybody out there?

Then the husky whispers of a neighbor, the old Latino man. “Don’t worry. It’s okay, you’re gonna be okay,” he tells Serpico. “I called the ambulance.”

He holds Serpico’s hand.

THE MEETING I met Frank Serpico in September, in the year 2000.

It’s been almost 30 years since his fellow officers set him up on that drug bust. Set him up because he believed in doing the right thing; because he believed in good cops. Set him up because he wouldn’t take a bribe or his share of the weekly take. Frank Serpico refused to look the other way, and he turned the New York City Police Department upside down by exposing rampant graft and corruption. When his superiors would do nothing about his accusations, he went to The New York Times. The front-page story led to the formation of the Knapp Commission, an in-depth investigation of corruption in the police department.

“Through my appearance here today,” he testified before the Knapp Commission, “I hope that police officers in the future will not experience the same frustration and anxiety that I was subjected to for the past five years at the hands of my superiors because of my attempt to report corruption….We create an atmosphere in which the honest officer fears the dishonest officer, and not the other way around.”

Because of his courage, a lot of cops went down during the years Frank Serpico was on the force. To good cops, he is a hero. To dirty cops, he is a rat. In the months following the shooting, the rumor was that the Mafia had a contract on his head. Some still want him dead.

During the months leading up to our meeting, I asked all kinds of people—my hairdresser, students, friends, my dad, strangers, Goth kids on the Mall, a few homeless guys (they all remembered and admired him), a waitress, a bus driver, the librarian, a couple of academics, some cops (they all remember him, too), a couple of musicians, a cab driver, my kids, “Do you remember Frank Serpico?” Some gave me this vacant stare, so I added, “Remember the movie, Serpico, with Al Pacino?”

“Is he still alive?” “Is he a real guy?” “Yeah, I really respect him, the way he stood up for what he believed in.” “Ummm…no, I don’t think so.” “He’s my hero, he’s why I became a cop.” “Is he in that band…you know the one, oh man, I can’t think of it. Do you know?” “Wasn’t he Al Pacino in that movie?” “MMMM, I think so. What was it he did again?”

So here’s this man who risked his life for what he believes in. A man who stood alone against corruption. I wonder what makes him tick. What is it that makes integrity more important than life itself? I want to know this, because there is so little to look to these days. So few heroes to emulate. We’re living in a time when world leaders are publicly accused of lying. A time when we hunger for gossip and the media obliges our cravings with daily doses of tabloid journalism. A time when few can hold onto hero-ship because we pick at the edges of the human scab until we make it bleed. And then when its raw underbelly is exposed, we shake our heads yes. We knew it. He was no good. I wonder what the cost of courage is. What price has Frank Serpico paid? How did this betrayal—being left in a pool of his own blood to die—change him? Who is he, really?

Now, as I sit in this little restaurant, somewhat of a cross between a hip trendy café and a New York diner, I wonder what to expect. We marked our calendars. Perhaps this, September 25, 1 p.m., will be our first and only meeting.

I’m five minutes early. It smells of good coffee, organic vegetables and cilantro. When I first walk in, two men at the counter stop eating, their forks halfway between plate and mouth. One’s wearing a black vintage shop jacket and 1950s hat, the other a white T-shirt and khakis. I’m thinking a town that still has nickel parking meters is small enough to know a stranger. A red-haired waitress comes up to me, her eyes questioning.

“Do you know Frank Serpico?” I ask, half-thinking he doesn’t live anywhere near here. So when she gives me her expressionless “yeah,” I am relieved.

“I’m meeting him, and we don’t know each other,” I explain. “Would you mind letting me know when he arrives?”

“You’ll know,” she says.

“I’ll know?”

“Yeah, you’ll know.”

It’s taken months to set this meeting up. The checking on me, my resume, my clips. It’s been a series of mediated conversations between Frank, his lawyer-nephew Vincent and me. And I still don’t know Frank’s phone number or exactly what town he lives in. It’s five after one, and here I sit—more than 500 miles from home, not even sure he’ll show.

ROOTS Frank Serpico is 64. An Aries. Each day, he checks what the stars have in store. Astrological stars, that is. He has little time for Hollywood or labels or anything that smacks of conformism. He speaks five languages, dances the tango and plays the harmonica and African drums. And he’s rarely without a woman. His friends are really acquaintances, and he’s not afraid to cry. When asked if he’s a vegetarian or an artist, he responds with another question, something he does a lot. “I don’t know, am I?” And then with eloquent poetic precision, he uses another’s words to describe how he feels:

Without consideration, without pity, without shame

They have built great and high walls around me.

And now I sit here and despair.

I think of nothing else; this fate gnaws at my mind

For I had many things to do outside.

Ah why did I not pay attention when they were building the walls.

But I never heard any noise or sound of builders.

Imperceptibly they shut me from the outside world.

(Constantine Cavafy, 1896)

The bullet left fragments in his skull, and his hearing is impaired. Still, he’s got much more compassion for the guy who shot him than for the ones who left him for dead. Frank says, “No doubt my life changed after February 3.”

He retired from the New York City Police Department after 11 years—a disability retirement a year after the shooting. The only thing Frank had wanted was to earn his gold shield (detective badge); the department finally gave it to him, promoting him after the shooting. They gave him the Medal of Honor, too. But what makes Frank mad is that the commendation is not for standing up to corruption, but for getting shot.

Where did this passion come from? Frank points to Vincenzo and Maria Giovanna Serpico, his parents. And even though Frank has traveled to many parts of the world, he’s still a Brooklyn kid. Sometimes in his innocence, he can momentarily look like the kid who shined shoes at the subway stops or stole away to catch glimpses of the huge goldfish at the Brooklyn Botanical Gardens.

When Frank talks about his childhood, he’s a different person. He’s calm, centered and laughs a lot. He tells how his father taught him to use a shoe hand polishing cloth. How he and his friends would get pictures of Jane Russell, the sex symbol of his time, erase her dress and fill in the missing pieces. He tells about going to the Brooklyn Museum to look at the jeweled Arabian daggers. “It was a magic carpet ride for me.”

In the mornings, Vincenzo woke Frank with a big cappuccino. “He’d boil milk and the left-over espresso from Sunday on Monday morning,” Frank says. “He would always have a glass of fresh-squeezed orange juice for me. And he’d make me a big sandwich for school. A round loaf, I can still see the cracked grain, and cut a hole in it and stuff it with meat balls.”

Frank says the kids would make fun of him, but Maria Giovanna said they were just jealous. He calls her a true macrobiotic and respects the way she would conserve energy, lighting candles at night. “The seeds are there, it’s so important the framework you build your life on,” he says.

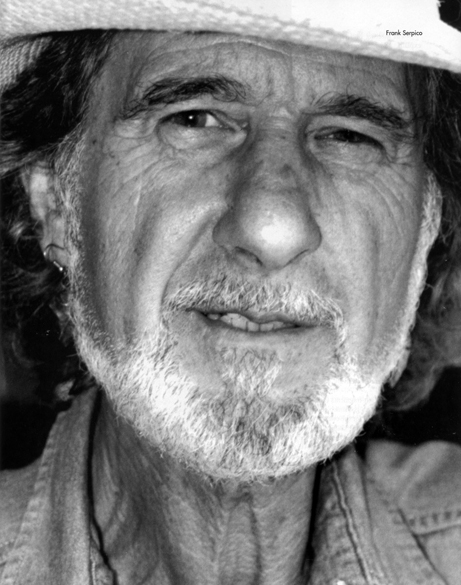

THE ENTRANCE He shows, about six minutes late. The waitress was right. I know. Frank’s movements are sweeping, theatrical. I feel his energy. He’s wearing sunglasses, two silver hoop earrings, a black shirt, black pants and a gray jacket. He’s got a Sean Connery-like white beard, and I notice he’s cut his shoulder-length hair. It’s in longer layers. I put my hand out; he kisses my cheek. I’m not sure why, but I expected he would be taller.

Barely in his seat, he pops back up. He removes his driving gloves, finger by finger. Then his jacket. Then the rounds: the chef, the two guys at the counter. He orders carrot and celery juice and a soy cappuccino, from two different waitresses. We talk about last night’s sky, the stars and his car date with his tango teacher. It’s a new car, a convertible white Toyota Spyder. They’re hard to find, he tells me. About five sentences later, he’s back up. “How’s your bladder?” he asks, before walking away. This time I watch him. His movements are just as I had expected. Just like Al Pacino portrayed him in the film.

“Yeah,” he says when I mention it. “People who know me say, ‘Al Pacino acts more like Frank Serpico than Frank Serpico.'” But I hear the tension. He doesn’t like the movie talk. Still, he shares that he met with Robert Redford in Greenwich Village before they cast the part. Redford was considering the role, Frank tells me.

He orders a salad, dressing on the side. I offer him my bread. He peppers a small ramekin of olive oil and dips the crusted end in, takes one bite and pops up, still chewing. “Gotta plug the meter,” he says, laughing. I can’t figure out what’s funny, so I ask when he returns. “That’s a line from the film.”

There are parts of the film that make him cringe, especially when Al Pacino is going across the bridge singing. “People say I have a great voice,” he tells me, now leaning into the table. “I love opera, I love to sing opera.” But if you ask him about Pacino, he reveals little. “Al Pacino is an actor,” he says. “I’m the real thing.”

“Hollywood is no different than the police force, with its corruption and racial profiling. Take my movie,” Serpico says, fingering the silver and glass object around his neck. “They make the bad guy black. I tell Sidney Lumet he wasn’t black, and he says to me, ‘Pussycat, I’m trying to make a movie.'” The way Frank tells it, after he was on the set for a while, there was a parting of the ways. They even took his rental car away.

Seems Frank got more than he bargained for in Hollywood, though. A woman he dated there got pregnant, and he was slapped with a paternity suit. But Frank did the right thing—he pays her half his monthly pension. And he sees his son, who is now 20, about four times a year.

Our conversation is about as disjointed as his eating. A bite here, a swallow there. But eventually he comes back to the topic. I ask about the glass object he continues to cradle. “It’s a talisman,” he says. I discover later that it’s his looking glass so he can read the fine print on food labeling.

“You wanna see something?” he asks, and pulls his wallet out. In the first plastic cover is his police I.D. badge from the 1970s. “See my eyes?” I look, but I don’t see. “See, across here.” He rubs his forefinger across the photo. “The Japanese call it sampuco, life out of balance.”

After about four hours, we go for a ride in the Spyder. Kids are yelling as we drive by. “Hey, Paco.” “Paco.” That’s what everyone calls him. But then he remembers he has a tango lesson in 30 minutes and drops me at the side of the road. “Tomorrow?” he asks. “Tomorrow.”

EUROPE Frank lived in Europe for more than a decade, with most of his time spent on a farm in Holland. These were some of the best, and the hardest, years. Suffering from post-traumatic stress, he studied the Bible, trying to solve it like a case, questioning everything. And now he’s working on what he calls the case against Moses.

In his search for answers, Frank found a spiritual group in England, The Order of the Star, and together they established a mind, body and spirit school (ORISA). “It was a wonderful concept, we allowed people to use their own innate creativity,” he says. “We would guide and support, rather than inhibit, children.” But eventually this endeavor fell short of Frank’s expectations. “Too culty,” he says, and he backed out. But working with kids stuck. He’s a natural. Today Frank teaches kids about nature and issues of integrity.

Some have called Frank Serpico a womanizer. So I ask him if he even likes women. At first, he seems insulted. Days later he tells me, “You’re right, I don’t like women. I like food. I love women, they are the yin of my yang.”

There have been many. But perhaps really only one. Marianne. A Dutch woman. The woman who lived with him in Holland. The woman he married in a spiritual wedding. The woman who died of cancer. The woman he says is his true soul mate.

Seems like some might have given up, after all that Frank endured. Some may have backed off, gotten selfish, not worried about the world anymore. Not Frank. His passion for doing the right thing only intensified. “Suffering is part of learning,” he says. He lets no one slide. “I know I’m a pain in the ass,” he says. “I’ve got to say what I feel.”

His hero? The controversial Thomas Paine. Interestingly, Paine was often ostracized by those who feared his free and sometimes radical opinions. And like Paine, Frank sees himself as a citizen of the universe. He gets fired up when he talks about his frustrations with the American system, Mario Cuomo, the police department and prisons. “Look at the corruption in Hollywood, the corruption in society,” he says. “What’s the answer? It starts with each person. It’s time to take responsibility.”

IN THE GARDEN, WET WITH RAIN Tonight he’s made a salad with nasturtiums from his garden. Bright orange and yellow. Maintaining that little bridge to the earth is important to him, he says. So now he tells me he wants to run in the dark. I suggest getting some kind of light. He cuts me off: that would defeat the purpose. We can do these things, he says. Like being able to see a spider’s gossamer strand in the woods.

As we talk this night, with me now back in Virginia, I consider how my thoughts have changed. Oh, yeah, I still think he’s a little crazy. He can still be exceedingly irritating. Perhaps a mirror of what we don’t want to see. Understanding Frank Serpico is more complicated than black and white. Even more complicated than gray. He’s got all these layers, and you have to peel them one by one, like an onion. Each thin sheath revealing just a little more insight. What strikes me most, though, is that I think sometimes he’s lonely and longs for what he can never have again. But then I think of his cabin tucked into the overflowing herbs and flowers that seem to shield him somehow.

I go to his cabin the day before leaving. I bring my dogs. We meet in a little village not far from his 50-acre plot. Parked across from the bagel shop, I see him in my rearview mirror. Looks like he’s got something on his mind, so I pretend not to notice him walking up behind me. “Hey lady, you want to get arrested for parking in the hot sun with these dogs in the car?” I guess we’re playing cop. And momentarily I’m annoyed.

He decides he wants a sandwich before he goes home and starts talking about some shop across the street. Mid-sentence, he stops. He sees some guy he knows driving by in a van and he’s off, running down the road after him. Once in the sandwich shop, the waitresses are not amused with his questions, his antics. But this time, it seems easier. At least they don’t pretend.

He gets a tuna salad on bagel and eats it in my car while I drive. Fall is already showing a light warning of winter’s death. We drive past the apple orchard and wind around several bends. His drive is hidden.

We go through his box of pictures. Frank as a kid. A soldier in Korea. Vincenzo. Pasquale, his brother. Frank in bikini underwear. Alfie, his dog. Other women. Lots of other women. His farm in Holland. The cops in the different precincts. Marianne. She’s so beautiful, he tells me. But he doesn’t have to say it; I can see her long reddish-blonde hair. Her youth. Her nose that seems to turn upwards, just a little. Yes, she is beautiful in that natural classic way. He shows me each image in the box. Slowly, gently, like they might break. Like he’s clutching each fragment of memory, the puzzle pieces that define his journey. “Careful, don’t touch them,” he says.

There’s white sage burning, and he’s drinking a glass of white organic wine. Josh, his extra-toed cat with paws that look more like a bear, smells my ankles and looks at Frank. Just as fast as it began, picture time is through. Frank calls the car dealer about a cassette tape the mechanics seem to have broken. So I look around. It’s the kind of place you feel at home in right away. It’s full, with African masks and goat-skinned drums. His sculptures. The ones he’s made. A giant fig tree nearly overtakes the wooden kitchen table.

The cabin is one large room, with alcoves, furniture and screens defining the bedroom, office, living room. He heats with wood. His life, here at the cabin, is simple, rich, sensual.

I have my answer. This is Frank Serpico: no mask, no pretending, no posturing. Here, in this place, I like him. He’s got his own goldfish pond and running trails he’s cleared with a machete. He’s got rabbits, chickens and five cats. He did have a goose till it flew away the other day. He’s got more herbs and edible plants than most greenhouses. And he respects the man who came to clean his septic tank more than he respects the President. “He was honest and forthright,” Frank tells me. “He had integrity.”

Before I leave, I ask Frank once more, “How do you want people to see you?” “Like

Oscar Wilde’s tailor, measuring me anew each time he sees me.”

We get in my car for the ride back to the village. He plays with the dogs, teasing them in a gentle sort of way. Of course, we have to make one more stop at the apple orchard for a few apples and some red and green peppers. I smile when I notice he’s wearing the leather bracelet he’s had made. The one with his gold detective’s badge in the middle.

I pull up behind his car. With his hand on the doorknob, he turns back to me. Just one more poem, he says, smiling that deep-down smile. “Disguised since childhood, haphazardly assembled from voices and fears and little pleasures, we come of age as masks. Our true face never speaks. Somewhere there must be a storehouse where all these lives are laid away like suits of armor or old carriages or clothes hanging limply on the walls. Maybe all the paths lead there, to the repository of unlived things.” (Rainer Maria Rilke)

He kisses both my cheeks, European style.

This article was originally published in the January/February issue of 2001.