Conversing with Nat Hentoff produces feelings of sincere admiration coupled with deep yet light-hearted envy. Aside from being a prolific writer and journalist whose work has appeared in The Washington Post, The New Yorker, The Village Voice, and numerous others, Hentoff’s self-proclaimed three life passions are jazz, the Constitution, and an atheist approach to anti-abortion. To add to that list, Nat is a nationally renowned civil libertarian and opponent of the death penalty.

Born in Boston on June 10, 1925, Nat Hentoff attended Northeastern University where he received a B.A. with highest honors and would later receive an honorary Doctorate of Law. Thereafter, Hentoff spent much of his career writing for numerous news publications, but he also hosted several jazz radio shows, wrote the album liner notes for artists like Bob Dylan, and authored numerous books on jazz, the Constitution, and the importance of civic education. While many individuals see some of Hentoff’s views as particularly idiosyncratic, perhaps this is understandable given that when asked of his ideological leanings, Hentoff has quipped that he is “a member of the Proud and Ancient Order of Stiff-Necked Jewish Atheists.”

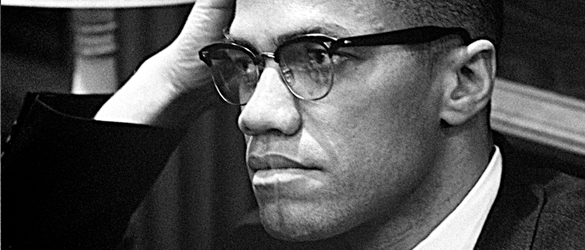

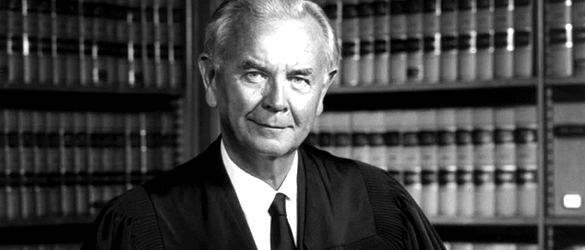

Nat Hentoff had the fortune of knowing many movers and shakers. On the jazz end there is Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, Louis Armstrong, and Dizzy Gillespie, just to name a few. In regards to civil rights and politics, Nat speaks warmly about his relationship with Malcolm X and key Black Panther member Eldridge Cleaver. On the topic of the Constitution and civil education in general, Nat describes his admiration for and relationship with the late Justice William Brennan, who also held the deep conviction that civic education is a necessity for American life.

Nat Hentoff had the fortune of knowing many movers and shakers. On the jazz end there is Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, Louis Armstrong, and Dizzy Gillespie, just to name a few. In regards to civil rights and politics, Nat speaks warmly about his relationship with Malcolm X and key Black Panther member Eldridge Cleaver. On the topic of the Constitution and civil education in general, Nat describes his admiration for and relationship with the late Justice William Brennan, who also held the deep conviction that civic education is a necessity for American life.

Hentoff is an icon and hero in his own right, but hearing him talk about some of his more notable acquaintances is truly a treat. It comes as no surprise that the 86-year-old seems to most admire those individuals who are still working with their passions, most notably Bob Dylan and Woody Allen. While the list of individuals is both exhaustive and impressive, one can tell that Hentoff is most fascinated by the legendary jazzmen he came to know both personally and musically. Nat warmly recollects a run-in with trumpet aficionado Dizzy Gillespie where the musician likened him to an “old broad,” a description that Nat took as a compliment and undoubtedly looks back fondly on. As a Jazz critic, author, and admirer, Hentoff finally got his due when, in 2004, the National Endowment of the Arts Jazz Initiative named Hentoff a Jazz Master. What makes this title all the more special is the fact that Nat is the first non-musician to receive the honor. While Hentoff has received numerous prestigious awards to accompany his Jazz Master title, one can assume that he is particularly tickled to have his name etched beside the masters.

This particular interview elucidates the fact that Mr. Hentoff still has the passion and desire to voice his claims and make a difference. And while the list of individuals that Nat has known throughout his life is impressive to say the least, a personal conversation with the man himself brings forth notions of glamour and wisdom, and the fact that Nat is a true and invaluable national treasure.

JWW: Nat, you’ve worked with and known a lot of notable people. Let’s start with Malcolm X.

NH: At first I had only heard about Malcolm in the black press. I used to read it, among reasons, because I was involved in the civil rights movement. But I also wanted to see if there was anything about jazz in it. Oddly enough there wasn’t. I was then writing for a magazine called The Reporter and when I heard about Malcolm X, I wanted to do a story on him. I found out where the mosque was in Harlem that he was then presiding over. I called the mosque and surprisingly they invited me over. When I arrived, I was the only white guy in the room. They gave me my coffee and I heard on the jukebox a wonderful singer singing about his hatred of white people. I walked over and saw his name was Calypso Joe and I knew who that was. It was Louis Farrakhan. This was my initial introduction to the culture surrounding Malcolm X. I waited but no Malcolm. So I finally headed toward the door and there was somebody sitting at the table near the door and he said, “Who are you looking for?” I said, “Malcolm X,” and he said “Sit down.” It was Malcolm himself and for an hour or so I was lectured to by the man himself. And then somehow we got to be friends but to our mutual surprise. Later we were both on a panel on the radio show and we both broke each other up. A lot of laughter.

JWW: What did he lecture you on?

NH: All about Elijah Muhammad and why he was known for black pride, black action and so forth. So anyway, we got to be friends. This was even while he was still with the Nation of Islam. He would call me at home sometimes. My wife, who answered the phone, was a very bold, courageous person. She would come to me and say, “Mr. X is on the phone.” And as we got to know each other and when he finally left the Nation of Islam, I saw what was happening. He had started another organization and in the last year of his life he was still in the Civil Rights Movement and fighting for equality. However, he was willing to work with whites with whom he agreed. The last time I saw Malcolm was at a radio station. He had just been interviewed and he said to me, “You know, my house was fire bombed.” With a surprised expression on my face, I said, “Yeah!” Malcolm said, “Well, I tried to go into a hotel yesterday because I was writing something and the phone rang and they said, ‘We know where you are Malcolm.'” Next thing I knew he was assassinated.

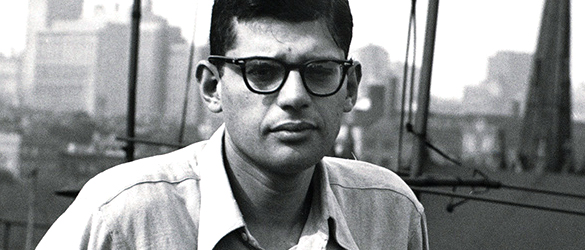

JWW: Did you work with any of the Beats? Did you know, for example, Jack Kerouac or Allen Ginsberg?

NH: I knew Kerouac because when I read On The Road I was much taken by it. However, there wasn’t much substance to the Beat movement. It was largely rhetoric. Kerouac once was at the jazz club here in New York City working with jazz musicians. So I got to know him then. I remember talking with one of his cohorts who was arguing that ROTC should be banned from the colleges. And I said, “Look, do you believe in the First Amendment?” – He said, “Yeah. Sure.” I replied, “Well, don’t you realize there are some of those students who want to hear what they have to say? Isn’t that violating the First Amendment?” He got very angry at me.

JWW: Did you know Allen Ginsberg?

NH: I got to know Allen fairly well. I must say Allen was such a strong free speech guy. And, of course, his famous poem “Howl” did a lot to alert people to what was going on in this country. He was a remarkable guy. He was himself. He was an original.

JWW: What about Lenny Bruce?

NH: I guess I probably knew him better than anybody. I so admired what he was doing and why he was doing it. For example, he often played in a club called The Village Vanguard. It was near where I lived. The Vanguard was one of the first clubs that had a naturally integrated audience. It was a jazz club. I heard him a lot. One of his routines shocked the audience. In fact, one night Lenny said, “Hey, are there any niggers here tonight? Any spics?” Everybody was about ready to stone him. And he said, “Why do you react so much to a word? Why don’t you think about where that word comes from?” Lenny was such a First Amendment advocate. Indeed, a First Amendment nut. I say that lovingly. And during the course of his trial, I went to his hotel room and all across the room, including the kitchen, there were books on the First Amendment. His trial of his for obscenity took place in New York City which was supposed to be the hippest city around. Lenny was convinced that if he lost in New York it was going to be the end of his career. But he expected he would win in the U.S. Supreme Court. At the trial I was a defense witness and I was examined on the stand by a lawyer named Richard Kuh who was soon to become the next District Attorney of New York City. The incumbent who brought the case against Lenny was about to retire. When I got on the witness stand Kuh asked, “Is it not true that you once supported a man who went into a military establishment in Nevada and tried to convince them not to commit war on Viet Nam?” I said, “Yes.” That was A. J. Muste, a very important man. Muste was one of the leading critics of the Viet Nam War. Kuh tried again and again to break me down. He didn’t. My testimony didn’t help the trial because the verdict was already preset. Lenny was found guilty. The last time I saw Lenny he was in San Francisco. He was at the club working. I could tell he was pretty bogged down. When he died, to everybody’s surprise the then Governor of New York Pataki decided to give Lenny a posthumous pardon under the name of free speech. It was sad that Lenny wasn’t around to see that.

JWW: You knew the jazz greats.

NH: I have I guess 3 passions. One is the Constitution. The other is jazz and the other is being an atheist prolifer which, of course, gets me in a lot of trouble — all of which combines into free expression. I knew Louis Armstrong somewhat but the person I knew the best was Duke Ellington. He was my mentor. I was so fortunate when I first started writing on jazz. I was on the radio. I met Duke and we talked and he gave me a lifelong lesson. He said he had just heard a disc jockey who talked about old time jazz, Dixieland and cutting edge jazz. Duke said, “Look. Do not categorize about music. You take each musician at the time and open yourself to that musician.” I have tried to do that with everything else that I do. And since you mentioned Duke, one of his important sidemen gave me a very important lesson for life. I learned so much from these guys but not only about their music. A guy named Ben Webster was a tenor saxophonist. He left Duke and was traveling around the country with his own combo. Most of the club owners wouldn’t pay for any extra money so Webster had to do what he could do with the local musicians to get them into the groove. One night in Boston he wasn’t making it. The band wasn’t making it. He was trying. We were sitting at the bar and he suddenly looked at me and he said “Kid, kid, when the rhythm section ain’t making it, go for yourself.” That taught me a lot of things about dealing with editors and I must say with former wives.

JWW: What about Dizzy Gillespie?

NH: Dizzy had the most generous spirit. I mean, he was so caring with everybody. The guys in his band loved him because he would take the time to educate them. He would sit them down at the piano and say, “Now, you got to know this stuff because that is where it all comes from.” Dizzy once gave me the biggest award I had ever had. It was unlike any other. I had not seen him for a few months and a band was rehearsing that he had picked for an all star concert. I think it was at the UN. So I got there and the musicians were there, but he wasn’t there. Dizzy comes down the hallway with a friend of his. He sees me and runs over and gives me a big hug and he says to the guy with him, “It’s like seeing an old broad of yours.” Now, nobody ever gave me that kind of compliment.

JWW: And you knew Billie Holiday.

NH: I once said that just meeting her on the street and hearing her say hello was a special kind of music in and of itself. She was somebody who went through a lot of bad times and always came out Billie Holiday. She was part of something I am exceptionally proud to be part of. There was a CBS Sunday afternoon television program called “The Sound of Jazz.” That was in the late 50s and the guy who did it was the most brilliant imaginative producer in all of television — a guy named Robert Herridge. He said to me and Whitney Balliett who was bringing in the musicians, “I want this to be pure, I don’t care if people know them or not.” Well, the musicians there were Count Basie, Thelonious Monk, Lester Young and Billie. You couldn’t get them together again. And when we had a lighting session Billie came in and I said, “I just bought a $500 gown for you Billie.” That really shocked her. That was a lot of money then. This is going to be a live show. I said, “Billie, look around you. This is the set.” The guys were wearing their hats as they usually do at a rehearsal and all that and the show was so moving. It has been played again all over the world and the most moving part of it was toward the end when Billie was surrounded by a small combo including Lester Young who had been a great influence on her. Lester called her “Lady Day” and she called him “Prez” after the president of the tenor saxophone. Once the set began they were talking to each other about music. It was so moving that in the control room I had tears in my eyes, and so did the producer and the engineer. It was just extraordinary. Anyway, when the show was over I came down in the studio and Billie, who had been so mad at me about the $500 gown, came over and kissed me. She was so pleased with the show. Now that was an award I will never forget.

JWW: Yeah, that must have been a great kiss to receive. You said you knew Louis Armstrong.

NH: The one time I really had a chance to talk to Louis at length was at a concert in Boston. As usual he knocks himself out. So he was pretty tired but nonetheless he let me talk to him for over an hour backstage. He went into quite a story about Jim Crow. Not only in New Orleans and the South, but he told me he was playing Connecticut in those years and they rode on a band bus. They come to a gas station. Louis wanted to go to the men’s room and one of the guys who owned the station saw them coming and rushed in and locked all the doors. Anyway Louis, when Governor Faubus of Arkansas refused to listen to the Supreme Court when they ordered the integration of the schools in Little Rock, in an interview attacked Faubus and attacked then President Eisenhower for not doing anything about racial discrimination soon enough. Joe Glaser who managed Louis was shocked. He sent a man down there to tell Louis to shut up and never do that again. But, of course, Louis did it again and again.

JWW: And then there was Bob Dylan.

NH: I first heard Dylan when he came to New York. He was playing at a club called Gerdes Folk City near where my wife and I lived. I had seen him a couple of times. I was not impressed with his guitar playing or for that matter with his voice. But I was very impressed with what he did with the lyrics. And then Robert Shelton of the New York Times wrote an article on Dylan, which made him a national figure. Soon after that I wrote a long piece on him for The New Yorker. I would meet him on the street in the village and he would say, “When is it going to run, when is it going to run?” Later I got to know him better. I was also responsible in part for a notorious interview with him. It has been anthologized. I did a Playboy interview with him. I had done other Playboy interviews with Joan Baez and the anti-war people. I did a normal interview with Dylan at Columbia Studios. Playboy had a proviso that I should never have agreed to. When they were ready to run an interview it had to be shown to the subject in case that person had something to object to. So one Saturday morning I was sitting ready to type and the phone rings. It’s Bob Dylan. He is furious. “They changed some of my stuff, I won’t allow that.” I said, “You know the deal with that. You just tell them not to run it.” Dylan said, “No. We are going to do another interview right now.” Fortunately I had a tape recorder on the desk. When we started the interview, I realized I was going to be the straight guy. Dylan was improvising surrealistically and very funny. I don’t know if you have ever seen the interview.

JWW: I have read it.

NH: So you can see. I never knew what the next question was going to be. I just had to improvise depending on what he was doing. I never knew where it was going to lead but I knew that was something that had never happened before. I have a lot of respect for Dylan. People should read his book Chronicles.

JWW: What did you think when he decided not to do protest songs anymore?

NH: Well, that was interesting. Dylan gave a speech before a very strong liberal organization. That is where he said he had had it with being a voice of protest. That shocked a lot of people. I think what happened to him was he also wanted to be himself — period. He didn’t expect at that time that what he said would be publicized and later widely known. Dylan was uncomfortable being known as just a protest singer. He wanted to go back into himself and do what he wanted to do when he wanted to do it.

JWW: You also knew Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver.

NH: Yes. I knew Eldridge very well. I had written a book for young readers called Journey into Jazz. It was about a white kid who was being taught by some black musicians on how to get in to the world of jazz. I got a phone call. I later learned that it was Cleaver. He wanted to know, “Is this book for adults too?” I said, “Sure. Anybody.” I later got to know more about Cleaver. He became, of course, very, very controversial and I got an interview with him for Playboy. So I arrived at Eldridge’s place, and the guys with guns escorted me into Eldridge. It was a very strong and interesting interview. And then we talked often after that. He was not, however, as thoughtful and as penetrating as Malcolm X was.

JWW: What about the Black Panthers? How did you feel about the Black Panther Party?

NH: Well, I am against anybody who uses violence to make their points and they did that. I got to talk to one of the guys who was on trial for murder. Malcolm, for example, made it very clear that if somebody goes after you– whether it’s cops or not– you have to defend yourself. But he was not an advocate for violence the way the Black Panthers were.

JWW: Malcolm X criticized Martin Luther King. Did you ever have any contact with Martin Luther King?

NH: Oh yes, once. I knew Bayard Rustin who was the guy who worked with King. Bayard organized the march on Washington at which Martin King made his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. He advised Martin on nonviolent resistance. I was doing a biography of A. J. Muste who was one of the leading strategists of nonviolent direct action against the Viet Nam War. In a phone interview with King, I said “Did you ever know A. J.?” And Martin Luther King said, “When I was in divinity school, this old man came in — A. J. always looked like an old man — and he started telling us about Gandhi and nonviolent resistance and it hit me and it stayed with me.” I thought that was very interesting.

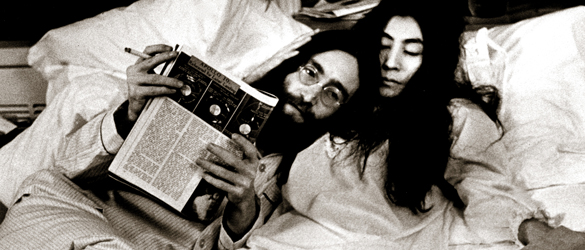

JWW: What about the Beatles?

NH: I did not know them directly. I loved a lot of what they did. There was some popular music I liked at the time although my main interest was in jazz, but the Beatles were fresh. They had fun with their music and that was a big help. They really had fun. They were not making it up. When John Lennon and Yoko had a bed-in for peace in their hotel room in Toronto, I was invited. So I went. My wife and I and spent a very amiable hour or so talking to both of them. There’s a photo of it. Some people are stunned that I was actually in his presence.

JWW: Yes, Lennon is treated like a god now.

NH: I was struck that he had a very lively subtle sense of humor.

JWW: And you worked with Woody Allen.

NH: I like Woody Allen an awful lot. I first knew of him as a standup comic. But he was a lot like Bill Cosby in that he did not say what you would expect somebody to say, and then when he did he went on and said other things you didn’t expect him to say. But he made me, for 33 seconds, a movie star in his film Sweet and Lowdown. It’s a movie on jazz and about the problems of the jazz guitarist. So he asked me to be myself in the movie and talk about this guitarist he was doing the movie on. Well, I get to the set. As we are warming up — you know he played clarinet in a Dixieland band — and we talked about what reeds he used. Then we started the filming. Before that he said, “All you have to do is look at me and talk to me.” I thought that was pretty good directing. So I was on for a brief period. That meant I had to join the Screen Actors Guild and all that. I recently got a performance check for 89¢. But it was a real kick to be in a Woody Allen movie. Woody is still producing good work. The people I admire are those who keep on producing and working and going on.

JWW: You knew Justice William Brennan.

NH: I knew Brennan very well. He had done so much to bring the Court back to the Constitution — such as the First and the Fourth Amendments. So I decided what have I got to lose. I called his chambers and asked if I could see Justice Brennan and interview him. It was Justice Brennan who answered the phone. He said, “Sure. Come on up.” So during one of the times I was in his chambers, we were talking and then he got very somber and said, “What are we going to do, what are we going to do with these kids in school, so that they can make the Bill of Rights part of their lives?” That is the question I keep writing about because we haven’t done it. Even civics classes have almost disappeared from the schools. So things have not gotten any better. With Bush, Cheney and Obama, we are seeing the same attacks on the Constitution. One of my biggest fears is as this goes on, and it can go on, kids will not make the Constitution part of their lives. They won’t know much at all about the Bill of Rights — the centerpiece of our democracy. We are going to have a long period where people are accustomed or conditioned to what’s going on now with the raping of the Fourth Amendment, for example.

JWW: Of all the people you have ever had contact with, who would be the person you would say you were most honored to be around?

JWW: Of all the people you have ever had contact with, who would be the person you would say you were most honored to be around?

NH: None of the ones I am talking about, although obviously I was much shaped and impressed by them. When I was a kid in Boston, it was one of the most anti-Semitic cities in the country. If you were living in the ghetto as I was, the Jewish ghetto part of Roxbury, and you went out alone at night, you might be subject to having people attacking you for being a Christ killer. The most popular radio show then across the country was Father Charles Coughlin who spoke out of the Church of the Little Flower in Royal Oak, Michigan. He was the most effective of all the anti-Semites. A friend of mine in Latin school introduced a woman to me named Frances Sweeney. She is the one who has most influenced my life. She was a devout Catholic. She was also furious at the anti-Semitism in Boston, spoke against it, wrote against it and was very angry that the Catholic press never said anything about it. So she went to see then Cardinal O’Connell, not O’Connor — I knew O’Connor later. O’Connell paid no attention to it. He almost threatened her with excommunication if she didn’t stop. Of course, she wouldn’t. Frances got some of us to attend various meetings including meetings of anti-Semitic groups. And that is when I learned not to take notes when people are watching you. But anyway, I so respected her and what she did for us. Then one day, she had us take a test as to what our prejudices were. The next meeting she threw the papers on the desk and said, “You are all a bunch of bigots.” Our own prejudices came out. That impressed me. But I supposed what most impressed me was she never stopped doing what she wanted to do. Her doctors told her to soften up her schedule. She had a heart condition. She had a heart attack on one of the main streets in Boston. She fell into the gutter and could not speak. But she did remember afterwards when she could speak that people would come by — I guess she looked very Irish to them — they didn’t do anything to help her. Some people would say, “See? Another Irish drunk.” She recovered from that for a short time. This encapsulates the kind of life I most admire.

—-

Malcolm X (Malcolm Little): Born May 19, 1925 in Omaha, Nebraska to a Baptist minister with strong sympathies toward the Black Nationalist movement, Malcolm grew up around the concept of Civil Rights. After living a troubled youth, Malcolm became a devoted Muslim and dropped his familial last name (Little) and instead used “X” to signify his lost tribal name. Malcolm became a national spokesman for the Nation of Islam (NOI) but would later found his own religious organization after becoming disenchanted with the NOI. After forming his own organization, Malcolm became more open to the idea of preaching to more than just African Americans. It was at this same time that Malcolm was the recipient of frequent death threats. Sadly, and before Malcolm could truly preach his new dream of integration and equality, those threats became a reality when, on February 21, 1965, Malcolm X was shot down by three gunmen (all members of the NOI) while giving a speech at a Manhattan ballroom. CLICK HERE to learn more.

Malcolm X (Malcolm Little): Born May 19, 1925 in Omaha, Nebraska to a Baptist minister with strong sympathies toward the Black Nationalist movement, Malcolm grew up around the concept of Civil Rights. After living a troubled youth, Malcolm became a devoted Muslim and dropped his familial last name (Little) and instead used “X” to signify his lost tribal name. Malcolm became a national spokesman for the Nation of Islam (NOI) but would later found his own religious organization after becoming disenchanted with the NOI. After forming his own organization, Malcolm became more open to the idea of preaching to more than just African Americans. It was at this same time that Malcolm was the recipient of frequent death threats. Sadly, and before Malcolm could truly preach his new dream of integration and equality, those threats became a reality when, on February 21, 1965, Malcolm X was shot down by three gunmen (all members of the NOI) while giving a speech at a Manhattan ballroom. CLICK HERE to learn more.

Jack Kerouac (Jean-Louis Kerouac): Born March 12, 1922 in Lowell, Massachusetts and learning English after he knew a French dialect called joual, Jack became impassioned with storytelling at a young age. Jack attended Columbia University in New York, but would soon drop out mainly due to complications with his football coach. Jack later joined the Merchant Marines and spent the majority of his free time with others involved in the Beat Generation such as Allen Ginsburg, William S. Burroughs, and Neal Cassady. His second and best-known work, On the Road, was completed in 1951, but it took quite a while before it was published. The eventual success and celebrity that On the Road brought Kerouac would prove daunting, leading the author to participate in perpetual alcohol binges and bouts of depression. Kerouac kept writing and publishing throughout his life, but unfortunately he died an early death in 1969, most likely due to complications stemming from his alcoholism. While Jack’s life was a mixture of grief and enlightenment, his writing has proved timeless and his role as a key figure in the Beat Generation remains unquestioned. CLICK HERE to learn more.

Jack Kerouac (Jean-Louis Kerouac): Born March 12, 1922 in Lowell, Massachusetts and learning English after he knew a French dialect called joual, Jack became impassioned with storytelling at a young age. Jack attended Columbia University in New York, but would soon drop out mainly due to complications with his football coach. Jack later joined the Merchant Marines and spent the majority of his free time with others involved in the Beat Generation such as Allen Ginsburg, William S. Burroughs, and Neal Cassady. His second and best-known work, On the Road, was completed in 1951, but it took quite a while before it was published. The eventual success and celebrity that On the Road brought Kerouac would prove daunting, leading the author to participate in perpetual alcohol binges and bouts of depression. Kerouac kept writing and publishing throughout his life, but unfortunately he died an early death in 1969, most likely due to complications stemming from his alcoholism. While Jack’s life was a mixture of grief and enlightenment, his writing has proved timeless and his role as a key figure in the Beat Generation remains unquestioned. CLICK HERE to learn more.

Lenny Bruce (Leonard Alfred Schneider): Born October 13, 1925 in Mineola, New York, Lenny became a famous comedian, satirist, and social critic. After serving in and seeing active duty in the Navy from 1942 to 1945, Lenny was discharged (first dishonorably but later reversed) for claiming to have homosexual urges. Bruce would later write screenplays, produce albums of original comedic material, and perform stand-up. Moving from New York to California with his wife, Lenny performed at strip clubs and found various other ways (some illegal) to secure a steady income. Lenny was first arrested for obscenity in 1961, and while he would be acquitted of that particular charge, Lenny would continue to be arrested for obscenity and was eventually convicted in 1964 despite strong support from individuals such as Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsburg. While out on bail during the appeals process in 1966, Lenny died of a narcotics overdose at his Hollywood Hills home. A biographical film based on Bruce’s life starring Dustin Hoffman was soon produced in 1974 and entitled Lenny. Furthermore, on December 23, 2003, New York Governor Pataki granted Bruce a posthumous pardon for his obscenity conviction. CLICK HERE to learn more.

Lenny Bruce (Leonard Alfred Schneider): Born October 13, 1925 in Mineola, New York, Lenny became a famous comedian, satirist, and social critic. After serving in and seeing active duty in the Navy from 1942 to 1945, Lenny was discharged (first dishonorably but later reversed) for claiming to have homosexual urges. Bruce would later write screenplays, produce albums of original comedic material, and perform stand-up. Moving from New York to California with his wife, Lenny performed at strip clubs and found various other ways (some illegal) to secure a steady income. Lenny was first arrested for obscenity in 1961, and while he would be acquitted of that particular charge, Lenny would continue to be arrested for obscenity and was eventually convicted in 1964 despite strong support from individuals such as Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsburg. While out on bail during the appeals process in 1966, Lenny died of a narcotics overdose at his Hollywood Hills home. A biographical film based on Bruce’s life starring Dustin Hoffman was soon produced in 1974 and entitled Lenny. Furthermore, on December 23, 2003, New York Governor Pataki granted Bruce a posthumous pardon for his obscenity conviction. CLICK HERE to learn more.

Duke Ellington (Edward Kennedy Ellington): Born April 29, 1899 in Washington D.C., Ellington was himself the son to two professional pianists. Duke began playing professional piano himself in the D.C. area in 1917. Ellington found initial success as a pianist/bandleader/composer in New York in the early 1920’s and would find mainstream success as early as 1926. Ellington toured the United States and Europe and successfully altered his style to the “swing” form of jazz that became widely popular in the 1930’s. Duke became an icon and legend of jazz, collaborating with some of the biggest names in the industry and receiving numerous awards. Ellington eventually died of cancer in 1974 and was succeeded as a bandleader by his son, Mercer. CLICK HERE to learn more.

Duke Ellington (Edward Kennedy Ellington): Born April 29, 1899 in Washington D.C., Ellington was himself the son to two professional pianists. Duke began playing professional piano himself in the D.C. area in 1917. Ellington found initial success as a pianist/bandleader/composer in New York in the early 1920’s and would find mainstream success as early as 1926. Ellington toured the United States and Europe and successfully altered his style to the “swing” form of jazz that became widely popular in the 1930’s. Duke became an icon and legend of jazz, collaborating with some of the biggest names in the industry and receiving numerous awards. Ellington eventually died of cancer in 1974 and was succeeded as a bandleader by his son, Mercer. CLICK HERE to learn more.

Dizzy Gillespie (John Birks Gillespie): Born October 21, 1917 in Cheraw, South Carolina, the legendary trumpeter began playing the piano at age four. Dizzy studied music in North Carolina and eventually made a profession out of touring and recording jazz. Gillespie is best known for helping usher in the be-bop era of jazz, largely due to his love for Afro-Cuban music and his Afro-American heritage in general. Sharing the stage with other legendary musicians and composers, Gillespie was respected by both listeners and other professionals. Dizzy would eventually tour the world over and die after a long and successful life in 1993 in New Jersey. CLICK HERE to learn more.

Dizzy Gillespie (John Birks Gillespie): Born October 21, 1917 in Cheraw, South Carolina, the legendary trumpeter began playing the piano at age four. Dizzy studied music in North Carolina and eventually made a profession out of touring and recording jazz. Gillespie is best known for helping usher in the be-bop era of jazz, largely due to his love for Afro-Cuban music and his Afro-American heritage in general. Sharing the stage with other legendary musicians and composers, Gillespie was respected by both listeners and other professionals. Dizzy would eventually tour the world over and die after a long and successful life in 1993 in New Jersey. CLICK HERE to learn more.

Billie Holiday (Eleanora Fagan): Born April 7, 1915 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Billie Holiday is considered one of the greatest jazz vocalists of all time. Holiday spent her young life in Baltimore but due to extreme poverty, was forced to drop out of school while in the fifth grade and procure a job running errands in a brothel. After moving to Harlem with her mother at the age of twelve, Holiday was eventually arrested for prostitution. Still poor and desperate for money, Holiday auditioned for a job as a singer at a local speak-easy and, by 1933, had her first big breakthrough. Throughout the 1930’s Holiday performed with other famous jazz musicians and eventually paired up with Lester Young to record some of the most notable jazz songs of all time. Holiday performed throughout the 1940’s and well into the 1950’s but her addiction to alcohol and narcotics eventually caught up to her and her voice. Holiday would die in a New York hospital in 1959 due to complications from liver and heart disease. CLICK HERE to learn more.

Billie Holiday (Eleanora Fagan): Born April 7, 1915 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Billie Holiday is considered one of the greatest jazz vocalists of all time. Holiday spent her young life in Baltimore but due to extreme poverty, was forced to drop out of school while in the fifth grade and procure a job running errands in a brothel. After moving to Harlem with her mother at the age of twelve, Holiday was eventually arrested for prostitution. Still poor and desperate for money, Holiday auditioned for a job as a singer at a local speak-easy and, by 1933, had her first big breakthrough. Throughout the 1930’s Holiday performed with other famous jazz musicians and eventually paired up with Lester Young to record some of the most notable jazz songs of all time. Holiday performed throughout the 1940’s and well into the 1950’s but her addiction to alcohol and narcotics eventually caught up to her and her voice. Holiday would die in a New York hospital in 1959 due to complications from liver and heart disease. CLICK HERE to learn more.

Louis Armstrong: Born August 4, 1901 in New Orleans, Louisiana, Armstrong is one of the most beloved jazz musicians of all time. Louis learned to play trumpet and cornet while at a juvenile delinquent home during his late childhood. Armstrong quickly became proficient on his instrument, playing in numerous bands and eventually securing a job as a member in a riverboat dance band. Eventually Armstrong’s idol King Oliver would ask Louis to come to Chicago to be a member of his band and play second cornet. It was through this gig that Louis gained his fame and showed the world just how talented he was. Armstrong was the first great jazz soloist and eventually showed his talent as a singer as well. Popular as a musician, comedian, and all around character his whole life, Armstrong would die at the age of 69 in 1971 in New York. CLICK HERE to learn more.

Louis Armstrong: Born August 4, 1901 in New Orleans, Louisiana, Armstrong is one of the most beloved jazz musicians of all time. Louis learned to play trumpet and cornet while at a juvenile delinquent home during his late childhood. Armstrong quickly became proficient on his instrument, playing in numerous bands and eventually securing a job as a member in a riverboat dance band. Eventually Armstrong’s idol King Oliver would ask Louis to come to Chicago to be a member of his band and play second cornet. It was through this gig that Louis gained his fame and showed the world just how talented he was. Armstrong was the first great jazz soloist and eventually showed his talent as a singer as well. Popular as a musician, comedian, and all around character his whole life, Armstrong would die at the age of 69 in 1971 in New York. CLICK HERE to learn more.

Bob Dylan (Robert Allen Zimmerman): Born in 1941 in Duluth, Minnesota, Dylan attended the University of Minneapolis where he became interested in folk music and started using the alias Bob Dylan. Dylan dropped out of college after one year but stuck around the city of Minneapolis to pursue a career as a folk musician. After going on tour and spending some time in New York, Dylan was signed to Columbia Records in the early 1960’s. Dylan gained initial fame by performing protest songs, usually just him and an acoustic guitar. Eventually Dylan grew tired of being pigeonholed as a folk protest singer and switched his sound up, a change that stirred public criticism and protests of its own. Despite listeners’ reluctance to accept anything other than the acoustic guitar wielding, protest song singing Dylan, he has been widely adored throughout his career. Dylan has traveled the world over and to this day still performs and writes music. Dylan is a true American legend who has inspired almost every singer-songwriter in some way. CLICK HERE to learn more.

Bob Dylan (Robert Allen Zimmerman): Born in 1941 in Duluth, Minnesota, Dylan attended the University of Minneapolis where he became interested in folk music and started using the alias Bob Dylan. Dylan dropped out of college after one year but stuck around the city of Minneapolis to pursue a career as a folk musician. After going on tour and spending some time in New York, Dylan was signed to Columbia Records in the early 1960’s. Dylan gained initial fame by performing protest songs, usually just him and an acoustic guitar. Eventually Dylan grew tired of being pigeonholed as a folk protest singer and switched his sound up, a change that stirred public criticism and protests of its own. Despite listeners’ reluctance to accept anything other than the acoustic guitar wielding, protest song singing Dylan, he has been widely adored throughout his career. Dylan has traveled the world over and to this day still performs and writes music. Dylan is a true American legend who has inspired almost every singer-songwriter in some way. CLICK HERE to learn more.

Eldridge Cleaver: Born in 1935 in Wabbaseka, Arkansas, Cleaver became interested in politics while in prison for a marijuana possession charge. After reading Thomas Paine, Marx, and Lenin, Cleaver joined the Black Panther Party (BPP) when he got out of prison. Eldridge obtained the position of Minister of Information and called for armed insurrection and a black socialist government. When the FBI became concerned with the work of the BPP, it was not long before Cleaver found himself a wanted man. During a police ambush on Cleaver and other members of the BPP, Cleaver fled but was eventually caught and charged with numerous crimes. Cleaver fled the country and stayed in exile for many years. Once he returned to America as a born-again Christian, Cleaver was put on trial but only received five years probation. Cleaver performed numerous good faith operations for the remainder of his life but struggled with drugs constantly. Eldridge died in 1998, cause unknown per his family’s request. CLICK HERE to learn more.

Eldridge Cleaver: Born in 1935 in Wabbaseka, Arkansas, Cleaver became interested in politics while in prison for a marijuana possession charge. After reading Thomas Paine, Marx, and Lenin, Cleaver joined the Black Panther Party (BPP) when he got out of prison. Eldridge obtained the position of Minister of Information and called for armed insurrection and a black socialist government. When the FBI became concerned with the work of the BPP, it was not long before Cleaver found himself a wanted man. During a police ambush on Cleaver and other members of the BPP, Cleaver fled but was eventually caught and charged with numerous crimes. Cleaver fled the country and stayed in exile for many years. Once he returned to America as a born-again Christian, Cleaver was put on trial but only received five years probation. Cleaver performed numerous good faith operations for the remainder of his life but struggled with drugs constantly. Eldridge died in 1998, cause unknown per his family’s request. CLICK HERE to learn more.

Martin Luther King Jr.: Born January 15, 1929 in Atlanta, Georgia, King entered into a family of pastors at the nearby Ebenezer Baptist Church. King attended Morehouse College for his B.A., Crozer Theological Seminary for his B.D., and Boston University for his Ph.D. In 1954, Dr. King became pastor of a Baptist church in Montgomery, Alabama. By this time King was also a member of the executive committee for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In 1955, King organized the legendary Montgomery Bus Boycotts that lasted for over a year and led to the U.S. Supreme Court ruling stating that segregated transportation was unconstitutional. King fought tirelessly for African Americans’ civil rights, penning the “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” manifesto and giving his “I Have a Dream” speech in front of 250,000 people. At 35, King was the youngest person to ever receive a Nobel Peace Prize. On April 4, 1968, King was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. CLICK HERE to learn more.

Martin Luther King Jr.: Born January 15, 1929 in Atlanta, Georgia, King entered into a family of pastors at the nearby Ebenezer Baptist Church. King attended Morehouse College for his B.A., Crozer Theological Seminary for his B.D., and Boston University for his Ph.D. In 1954, Dr. King became pastor of a Baptist church in Montgomery, Alabama. By this time King was also a member of the executive committee for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In 1955, King organized the legendary Montgomery Bus Boycotts that lasted for over a year and led to the U.S. Supreme Court ruling stating that segregated transportation was unconstitutional. King fought tirelessly for African Americans’ civil rights, penning the “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” manifesto and giving his “I Have a Dream” speech in front of 250,000 people. At 35, King was the youngest person to ever receive a Nobel Peace Prize. On April 4, 1968, King was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. CLICK HERE to learn more.

John Lennon and Yoko Ono: When the famous couple decided to marry, they turned the event into an opportunity to promote world peace. They were married in 1969 during the height of the Vietnam War and wanted to turn the publicity of the occasion into a medium to promote their anti-war beliefs. During two separate weeks—one in Amsterdam and one in Montreal—John and Yoko held “bed-ins” to nonviolently promote peace. The idea for a “bed-in” came from the “sit-ins” of the American Civil Rights movement. The bed-ins were successful, drawing much attention from fans and the media. CLICK HERE to learn more.

John Lennon and Yoko Ono: When the famous couple decided to marry, they turned the event into an opportunity to promote world peace. They were married in 1969 during the height of the Vietnam War and wanted to turn the publicity of the occasion into a medium to promote their anti-war beliefs. During two separate weeks—one in Amsterdam and one in Montreal—John and Yoko held “bed-ins” to nonviolently promote peace. The idea for a “bed-in” came from the “sit-ins” of the American Civil Rights movement. The bed-ins were successful, drawing much attention from fans and the media. CLICK HERE to learn more.

Woody Allen (Allen Konigsberg): Born December 1, 1935 in Brooklyn, New York, Woody is a comedian, actor, director, musician, and all-around artist. Starting his career at age 15 selling one-liners to a local newspaper, Woody’s climb to fame was a quick one. Woody moved on to stand-up comedy and later became an actor and screenwriter. Allen has won 3 Academy Awards and has been nominated a total of 23 times. Woody is also a jazz clarinetist and performs regularly in small Manhattan clubs. Regarded as one of the best filmmakers of our time, Woody is a living legend. CLICK HERE to learn more.

Woody Allen (Allen Konigsberg): Born December 1, 1935 in Brooklyn, New York, Woody is a comedian, actor, director, musician, and all-around artist. Starting his career at age 15 selling one-liners to a local newspaper, Woody’s climb to fame was a quick one. Woody moved on to stand-up comedy and later became an actor and screenwriter. Allen has won 3 Academy Awards and has been nominated a total of 23 times. Woody is also a jazz clarinetist and performs regularly in small Manhattan clubs. Regarded as one of the best filmmakers of our time, Woody is a living legend. CLICK HERE to learn more.

William J. Brennan: Born April 25, 1906 in Newark, New Jersey to Irish immigrants, Brennan graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1928 and Harvard Law in 1931. Early in his career, Brennan worked as a labor law attorney and a JAG during World War II. In 1949, Brennan was appointed to the New Jersey Superior Court and then, in 1952, to the New Jersey Supreme Court. President Dwight D. Eisenhower nominated Brennan to the United States Supreme Court in 1956, a decision the President later regretted due to Brennan’s decidedly liberal approach to the law. Believing in a living Constitution, Brennan tirelessly fought for what he saw as best for the country. Brennan was on the Court for 34 years and authored over 1,300 opinions. He died after a long and prosperous life in 1997. CLICK HERE to learn more.

William J. Brennan: Born April 25, 1906 in Newark, New Jersey to Irish immigrants, Brennan graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1928 and Harvard Law in 1931. Early in his career, Brennan worked as a labor law attorney and a JAG during World War II. In 1949, Brennan was appointed to the New Jersey Superior Court and then, in 1952, to the New Jersey Supreme Court. President Dwight D. Eisenhower nominated Brennan to the United States Supreme Court in 1956, a decision the President later regretted due to Brennan’s decidedly liberal approach to the law. Believing in a living Constitution, Brennan tirelessly fought for what he saw as best for the country. Brennan was on the Court for 34 years and authored over 1,300 opinions. He died after a long and prosperous life in 1997. CLICK HERE to learn more.