Drove from Paris to the Amsterdam Hilton,

Talking in our beds for a week.

The newspaper said, “Say what you doing in bed?”

I said, “We’re only trying to get us some peace.”

—John Lennon, “The Ballad of John and Yoko” (1969)

It was 1969, and the Vietnam War was raging. Protests, riots and societal turmoil were ripping at the seams of the western world. Into this political furnace stepped the unlikely characters of John Lennon and Yoko Ono.

John and Yoko married in March, checked into the Amsterdam Hilton in Holland for their honeymoon and, to the surprise of many, immediately announced that a “happening” was about to take place in their bed. Holland was permissive, but even the chief of Amsterdam’s vice squad issued a warning to anyone planning to attend. Despite this, 50 news people crowded outside John and Yoko’s hotel room, Suite 902. “These guys were sweating to fight to get in first because they thought we were going to make love in bed. That’s where their minds were at,” Lennon later recalled.

This week marks the 42nd anniversary of John and Yoko’s first infamous bed-in for peace in Amsterdam. Immortalized in the Beatles’ song “The Ballad of John and Yoko,” the bed-ins were much more than sensational media events staged by celebrities for whom the “cause” is politically expedient and risk-free, which we see so much of today. Rather, the bed-ins for peace (and against war) were John and Yoko’s way of taking a moral stand on what they considered to be theissue of their day, and they paid the price for it.

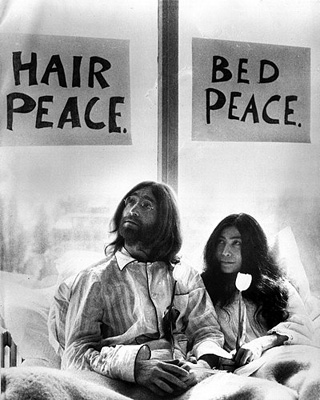

The concept of the bed-ins and their “origins lie in Yoko’s days as a performance artist, and the notion that spectacular public action can be an art form in itself,” writes Paul DuNoyer in We All Shine On(1997). “John, too, was shrewdly aware of how the ‘bed-in’ concept might titillate the press and TV crews with its implicit (though ultimately unfulfilled) promise of sexual exhibitionism.” However, when newsmen entered the room, John and Yoko were sitting in bed, wearing pajamas. And they announced that they would stay in bed for a week as “our protest against all the suffering and violence in the world.” The idea was to use the amazing image that Lennon the Beatle possessed in order to promote peace.

For seven days, starting on March 26, John and Yoko conducted interviews ten hours a day, starting at ten in the morning. In response to their efforts, a media frenzy ensued. “We did the bed-in in Amsterdam just to give people the idea that there are many ways of protest,” Lennon said. “Protest by peace in any way, but peacefully. We think peace is only got by peaceful methods. To fight the establishment with their own weapons is no good because they always win, and they’ve been winning for thousands of years. They know how to play the game of violence.”

One interviewer, however, noted that some were not taking John and Yoko and the bed-ins seriously, saying they were humorous. Lennon replied, “We stand a better chance under that guise, because all the serious people like Martin Luther King and Kennedy and Gandhi got shot.”

Strangely enough, Lennon’s antics raised the ire of both the Left and the Right. Indeed, Lennon’s pacifism seemed misplaced to the Left. As one columnist for the Village Voice wrote, “Lennon would never have achieved enlightenment if thousands of his forbears hadn’t suffered drudgery far worse than protest marches and cared enough about certain ideals—and realities—to risk death for them.”

If the Left was hostile, the establishment press was outraged by the bed-ins. “This must rank as the most self-indulgent demonstration of all time,” one columnist wrote. To John and Yoko, for whom the bed-ins were deeply personal, the stark criticism cut deeply. As Lennon later lamented in “The Ballad of John and Yoko”:

Christ you know it ain’t easy,

You know how hard it can be.

The way things are going

They’re gonna crucify me.

Despite the criticism levied against the bed-ins, they represented an astute exercise in media politics. “John and Yoko rejected the view held by many in the antiwar movement,” writes professor Jan Wiener in Come Together: John Lennon in His Time (1991), “that the newspapers and TV were necessarily and exclusively the instruments of corporate domination of popular consciousness. The two of them sought to work within the mass media, to undermine their basis, to use them, briefly and sporadically, against the system in which they functioned.”

As a media event, the Amsterdam bed-in and subsequent ones held by John and Yoko certainly made headlines, but were they effective in helping the anti-war movement? It was a question that frustrated Lennon to no end. For example, when asked about the success of the bed-ins, an irritated Lennon responded, “Some guy wrote, ‘Now, because of your event in Amsterdam, I’m not joining the RAF, I’m growing my hair.’” And when a skeptical reporter asked whether staying in bed meant anything, Lennon replied, “Imagine if the American army stayed in bed for a week.”

While the first bed-in in Amsterdam was historically significant , the second one in Montreal was musically significant, resulting in one of the great peace anthems of the 20th century when Lennon composed and recorded “Give Peace a Chance” in his hotel room. As DuNoyer writes:

By 1 June John felt he had a powerful peace anthem on his hands, and ordered up a tape machine. Still in bed with Yoko, with a placard behind them proclaiming “Hair Peace”, he invited all his varied guests (including the LSD guru Timothy Leary, comedian Tommy Smothers on guitar, singer Petula Clark, a local rabbi and several members of the Montreal Radha Krishna Temple) to sing along to his new composition. “Give Peace a Chance” was a chugging, repetitive mantra, interspersed with John’s impromptu rapping, a babbled litany of random name-checks (ranging from the novelist Norman Mailer to the English comedian Tommy Cooper) and impatient dismissals of “this-ism, that-ism”. The rapping was a decade ahead of its time. But it was not of primary importance, for this was another of John’s “headline” songs (in the tradition of “All You Need Is Love” and “Power to the People”) whose deliberately simplistic chorus mattered far more.

Years later, Lennon said, “In my heart, I wanted to write something that would take over ‘We Shall Overcome.’” With “Give Peace a Chance,” he succeeded. In fact, within several months of recording the song it was being played on radio stations around the world.

By October of 1969, “Give Peace a Chance” was a universal chant at anti-Vietnam War demonstrations. On November 15, during a peace rally in Washington, DC, the legendary folk singer Pete Seeger led nearly half a million demonstrators in singing “Give Peace a Chance” at the Washington Monument. “The people started swaying their bodies and banners and flags in time,” Seeger later recalled, “several hundred thousand people, parents with their small children on their shoulders. It was a tremendously moving thing.”

Later, Lennon was asked what he thought about that day. “I saw pictures of that Washington demonstration on British TV, with all those people singing it, forever and not stopping,” he said. “It was one of the biggest moments of my life.”

At year’s end, Lennon told interviewer Barry Miles: “There’s a mass of propaganda gone out from those two bed-ins… Every garden party this summer in Britain, every small village everywhere, the winning couple was the kids doing John and Yoko in bed with the posters around… Instead of everybody singing ‘Yeah Yeah Yeah’ they’re just singing ‘Peace’ instead. And I believe in the power of the mantra.”

Just before leaving Great Britain in 1971 to live in America, Lennon told biographer Ray Coleman, “I’d like everyone to remember us with a smile. But, if possible, just as John and Yoko who created world peace forever. The whole of life is a preparation for death. I’m not worried about dying. When we go, we’d like to leave behind a better place.”

“Give Peace a Chance,” the one lasting remnant of the bed-ins, was to enter the world’s consciousness more completely than any other song Lennon wrote. Eleven years after the infamous bed-ins, as tearful mourners gathered outside the Dakota Building on the night of Lennon’s murder, this was the song that they instinctively chose to express their grief and commemorate his life.

When the management at the Amsterdam Hilton Hotel heard the news of John Lennon’s death, they turned out all the lights in the building as a mark of respect—that is, with the exception of Suite 902, which shone like a beacon over the city. That room is now a museum of sorts with a collection of books, videos and paraphernalia on both Lennon and the Beatles. And fittingly, on the ceiling are the opening words to “All You Need Is Love”:

There’s nothing you can do that can’t be done.

Nothing you can sing that can’t be sung.

Nothing you can say but you can learn how to play the game

It’s easy.

This is a good article. Factual as to the best of my knowledge. on a side note: It sort of amazing me that John could have had any chick on the planet and Ono was the one. Wow, I am yet to find a sexy picture of that girl. Correct me if I am wrong, are there any?. But I guess that isn’t the point and when I listen to songs like “watching the wheels go round” I can better understand what John might have been about – that it must have been something deeper than that.