Now that my cable provider has gotten ahold of a batch of old Samuel Goldwyn movies, no doubt at a bargain price, I have had the opportunity in recent weeks to see some real classics, like The Best Years of Our Lives (1946) and The Little Foxes (1941), for example. But classic or not, these films are worth watching as anthropological treasure troves, telling us more about America than a thousand books, for what they reveal are the unspoken assumptions of American life.

However, there is another side to them as well, an ironic side. The characters in these films have no idea what is just around the corner. Their innocence – the innocence of people living in the 1940s about what was coming in the 1950s, the innocence of people living in the 1950s about what was coming in the 1960s – casts America’s social history into very broad relief. One such film is Our Very Own (1950). The story is simple: Gail Macaulay (Ann Blyth) learns just before her eighteenth birthday that she was adopted and sets out to find her biological mother, discovering in the end that what really counts is her adoptive family, which has always been there for her. The genre is neo-sentimental, with a suitable sound track. The dialogue is wooden. It is Dickens transposed to an American milieu, but without the Dickensian humor, or grotesqueness.

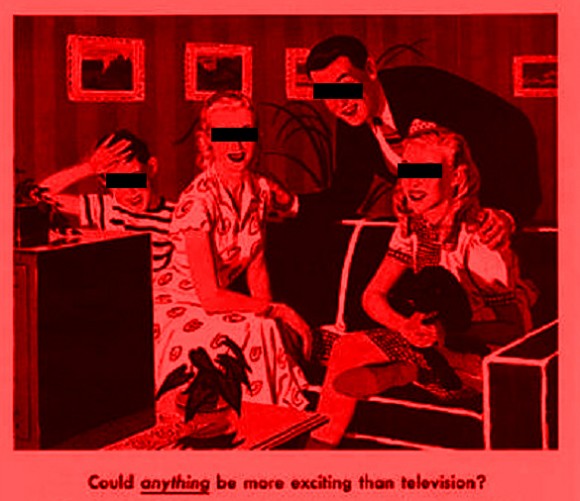

The Macaulays have everything you could want: three daughters, a dog, a cheerful black maid, and a new television set. We are on the threshold of the 1950s. This is a world where children ask to be excused from the dinner table and are sent to their rooms when they misbehave. Momentous things are about to happen: rock ‘n’ roll, fast food, the pill, suburbia, the beatniks, Communism, integration, and most of all – television. In fact, in the opening scene, the new television set is just being installed, and Natalie Wood as the precocious kid sister is pestering the TV men. It matters very little what the film had to say about adoption, which is not very profound. What matters is what it couldn’t say about the shape of things to come.

Television, as we all know, was one of the factors that contributed to the breakdown of family life in America. The Macaulays are not shown actually watching TV but we know that they are going to be watching an awful lot of it in the coming decade, each in his or her private cocoon. Henceforth, too, they will be getting most of their information about the world from their television set. This information will be served up to them by reporters and analysts who lack the talent, knowledge and understanding to be historians, scholars, political scientists or even novelists. Such being the standards of journalism, most will not even speak the languages of the countries they report from and comment on, so you can say that it will be a case of the blind leading the blind. And while news broadcasts will themselves become a form of entertainment, with plenty of red meat for the voyeurs and the bloodthirsty, shamelessly exploiting the grief and misery of real people to get their most “powerful” moments, others will be in charge of entertainment proper at the TV networks, bringing viewers game shows, variety shows, sitcoms, dramas (Bonanza, Gunsmoke, Maverick, I Love Lucy, The Honeymooners, Ozzie and Harriet, Ed Sullivan, Jack Benny, Lassie, Leave It To Beaver, What’s My Line?). Television of course can’t be blamed for everything. Personal computers, cell phones and social networking were quite some distance away, but the idea of wiring consumers into a communications system that made a lot of money for a lot of people was now in place. It should be understood that if there was no money in all of this, none of it would exist. Creating better products for better living is not an end in itself, as Marx pointed out. It is an intermediate stage, “a necessary evil of money making.” If money grew on trees, there would be no industry and certainly no sitcoms.

The genius of modern communications has been to take human needs – the need for information, the need to be entertained, the need to be heard – and to commercialize them around the lowest common denominator. I call this genius because whereas we would think that the natural tendency of an organized society would be to elevate this common denominator, as the educational system indeed attempts to do, however unsuccessfully, the media operate to drag it down even further, habitually playing to our worst impulses and thereby capturing our attention in spite of ourselves.

Does this mean that the Macaulays lived in a better America? Not really. Greed was always part of American life, as were conformity, bigotry and hypocrisy. The Sixties would at least tone down sexual repression and racial discrimination but it would not liberate Americans from the American Dream. This was the dream of the Macaulays in 1949 and this would be the dream of Gail Macaulay’s children in 1969. Television would bring the dream into even sharper focus, assuring them that anyone could be rich and famous. Television would also show old movies of course, making Gail Macaulay’s children wonder, maybe, how they had become what they were.