“Little Mister Prose Poet,” as Russell Edson calls himself, is a writer with a unique and surreal vision for his art. His work blurs the lines of prose, poetry, reality, and dreams. Edson remains a fairly obscure literary figure, but the tides of the twenty-first century might carry this old recluse to some strange shore of recognition.

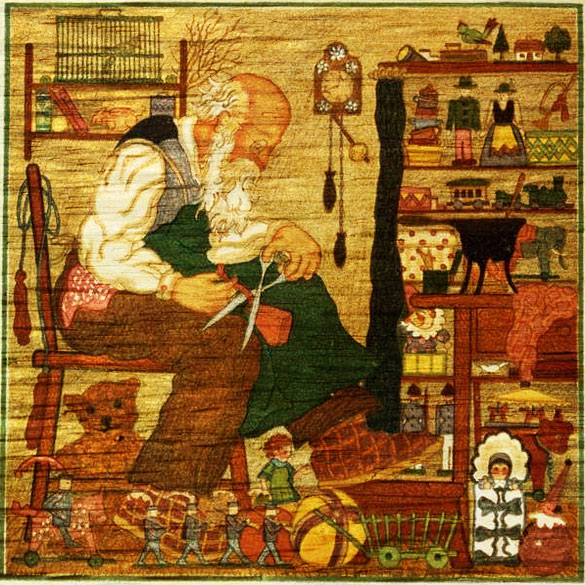

If any writer wanted to express bemusement, contempt, hopelessness, or happiness in the most creative way possible, Russell Edson could outwit them with ease. His pieces are quaint and amusing on the surface, but those facades are channels through which his emotional and philosophical currents flow. His piece “The Toy Maker” is poignant, off-putting, and funny all at once. The last line, “But best of all, he liked making toy shit,” is good for a chuckle, but might distract the reader from other images in the poem. “Toy god,” “toy heaven,” and “dying toy,” are some of the more haunting parts of the piece. A twentieth century reader looking at this piece might shrug and laugh, but readers in the twenty-first century want concise, entertaining, and sometimes insightful material. “The Toy Maker” is the paragon of what a twenty-first century piece of literature should be. It combines the Calvino-esque qualities of quickness and exactitude by firing off bursts of wit in medium-length lines and moving through the narrative with an eerie fluidity.

Like the character of the toy maker, Edson constructs his own worlds with parts of thoughts and feelings. His worlds are like funhouse mirror images of the everyday world. He creates realms where literally anything can happen. I might even be mistaken to call the toy maker a character, as that would imply a strict sense of narrative. His works are not narrative poems, because they seemingly tell stories of nothing in a very clever way. “Oh My God, I’ll Never Get Home” is a perfect example. In this poem, a man falls apart while walking home. Instead of fleshing out a character that metaphorically falls apart because of his woes, a man who the reader knows nothing about crumbles physically piece by piece. His preoccupation with getting home can be seen as both amusing and disturbing. If one were to look at this character’s home as a geographical place, it’s funny to think about him wanting to go somewhere while physically discombobulated. On the other hand, if his home were more of a concept and a feeling, the poem would take on a more haunting meaning. The man could be falling apart because of a deep existential loneliness, perhaps one that Edson himself felt when he wrote the poem. This combination of a cartoonish surface and a melancholy undercurrent could be a big part of the new literary era.

Reading Edson’s work was like simultaneously getting the feelings I got from Shel Silverstein’s work when I read it at ages six and sixteen. I was amazed at how simply and amusingly both writers had worded such complex emotions. The illustrations that accompanied Silverstein’s stories and poems did add that more innocent dimension to them, so maybe illustrations would add something to Edson’s work. Although, the only people I could even remotely suggest as Edson’s illustrators would be Salvador Dali and the person who did the illustrations for those Ginsberg poems. Edson has an extremely visual style, but they’re visual in the same sense that dreams are visual. You might see people turning into wooden objects or elephants with spider legs, but Edson is probably the only person who can accurately verbalize those things just as Dali is probably the only person who can accurately paint them.

Bob Dylan also comes to mind as a contemporary of Edson’s from outside of the literary field. Dylan’s albums from the mid-1960s express that same dreamlike silliness with a darker undercurrent. Songs like “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream,” “Motopsycho Nitemare,” and “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again,” all seem to come out of an amphetamine and acid induced lyrical carnival. While this may be true, both he and Edson voice their opinions on personal and societal problems without having to tackle them directly. Their personal lives also seem to draw parallels as both of them were hermits for a time. This anti-social behavior could have been a result of their frustration over people misunderstanding their creative impulses. People as creative as those two sometimes fear the world as much as the world fears them. That sense of fear is not the perception of a threat as much as the way people fear the sun. They respect, love, and cherish it, but heat and the poisons of UV rays can be deadly. Art and beauty can be as destructive as they can be creative. Dylan and Edson are in a way, victims of their own talent, ideas must be burning inside of them like a cancer, so they have to spend half of their waking lives in creative solitude. When these two die, they’ll be free of that yearning, but they’ll also take away major sources of ingenuity from the world.

—

Tyler Kutner is a graduate of Carver Center for Arts and Technology’s Literary Arts program, a two time Scholastic Regional Gold Key winner for poetry, and a second year student in University of Maryland’s Jimenez-Porter Writers’ House. Born with Cerebral Palsy, Tyler is a disability advocate and hopes he might eek out a living between freelance writing and public speaking.