“I am not a meek conformist but a tired nonconformist.”—Rod Serling

On Friday, October 2, 1959, The Twilight Zone premiered on national television. Even though it was never a top 25 show, The Twilight Zone was an oasis in television wasteland that captured a generation. However, it almost didn’t happen. Its subject matter troubled television executives, and the fact that the episodes often left viewers hanging went against formula.

I was barely 13 when I saw the pilot episode, “Where Is Everybody?” It left me speechless and compelled me to watch the following 156 episodes (which aired from 1959 to 1964).

The fact that children were fascinated by the show caught television executives off-guard. As Zone producer Buck Houghton recalls, “The appeal to children was a complete surprise to us. We never thought of that. I don’t think CBS did, either; it was on at ten o’clock. We got a lot of nasty notes from parents saying, ‘You’re keeping the kids up!’”

Children quickly picked up on the most basic plot elements—Martians, space or time travel, talking dummies or dolls, grotesque creatures and the like. Although young people initially enjoyed the stories on a superficial level, they are in many ways more intelligent than adults, more honest and eager to learn. “Maybe that’s because kids are hungry for the full play of their imagination,” Zone writer Charles Beaumont commented, “while the elders are inclined to fear it.”

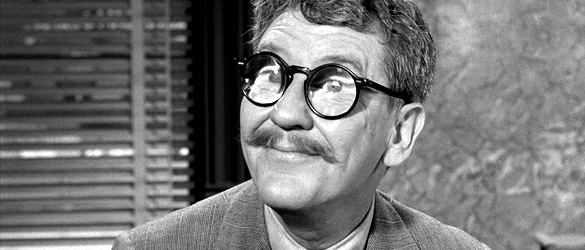

Most Zone episodes dealt with vulnerability and the conflict of emotions that make up the human condition. Besides great storytelling, Rod Serling, the show’s creator, was a genius who had something to say. His onscreen narration tied the show together, but it also gave Serling the chance to moralize. He often emphasized the moral of the story, just in case we had missed the point. And unlike most television shows people watch today, Serling challenged his viewers while entertaining them with substance and intelligent subject matter. He was a teacher. In fact, Rod Serling can be seen as a “video Aesop, using the show … to comment metaphorically on the aspects of human behavior and the human condition.”

But what makes The Twilight Zone—a show that many critics view as the best television series of all time—endure as a classic? Why does the series still influence both film and art? And why does it still speak to us today?

At its most basic aesthetic level, as Dan Presnell and Marty McGee note in their insightful book on the Zone, the series “can best be described as the ultimate Rorschach: No matter how many people have seen the series, they all see something different.” As Stephen King sums it up in Danse Macabre:

Of all the dramatic programs which have ever run on American TV, [The Twilight Zone] is the one which comes close to defying my overall analysis. It was not a western or a cop show (although some of the stories had western formats or featured cops ‘n’ robbers); it was not really a science fiction show… not a sitcom (although some of the episodes were funny); not really occult (although it did occult stories frequently—in its own peculiar fashion), not really supernatural. It was its own thing.

The Twilight Zone was a paradox. Although the series is often seen as science fiction, ultimately it was not science fiction. Whatever weird or far out setting may have been involved in a particular episode, the focus was always on the angst, pain and suffering we face in the so-called “real” world. As author Marc Scott Zicree writes:

The Twilight Zone was the first, and possibly only, TV series to deal on a regular basis with the theme of alienation—particularly urban alienation…. Repeatedly, it states a simple message: The only escape from alienation lies in reaching out to others, trusting in their common humanity. Give in to the fear and you are lost.

Serling dealt with a human nature that was stressed to the max by a modern society dominated by emerging technology as commandeered by an authoritarian state. In fact, a question raised in many Zone episodes was whether or not we can maintain our basic humanness in a world dominated by machines.

Finally, Serling took pride in the writing—penning 92 of the 156 episodes. Besides himself, however, some of the best writers of the 20th century wrote Zone episodes: Ray Bradbury, Richard Matheson, Charles Beaumont, Earl Hamner, to mention a few. As such, the Twilight Zone became the embodiment of great story-telling.

Although there are so many to choose from, the following are 12 of my favorite episodes:

Time Enough at Last: Mild-mannered Henry Bemis (Burgess Meredith), hen-pecked by his wife and brow-beaten by his boss, sneaks into a bank vault on his lunch hour to read. He is knocked unconscious by a shockwave that turns out to be a nuclear war. When Bemis regains consciousness, he realizes that he is the last person on earth.

I Shot an Arrow into the Air: Three astronauts survive a crash after their craft disappears from the radar screen. They find themselves on what they believe to be a dry, lifeless asteroid. Only five gallons of water separate them from dehydration and death. And temperamental crew member Corey (Dewey Martin) goes to great lengths to ensure his survival.

The Howling Man: During a walking tour of Europe after World War I, David loses his way and comes to a remote monastery. He is turned away but passes out, and the monks take him in. David regains consciousness and hears a bizarre howling. He eventually finds a man in a jail cell who the monks say is the Devil himself, kept in his prison by the “staff of truth.”

Eye of the Beholder: Janet lies in a hospital bed, her face wrapped in bandages, hiding the hideous face that has made her an outcast all her life. This is her eleventh hospital visit and the last allowed by the government. The faces of the doctors and nurses are also hidden by shadows and camera angles. Janet’s bandages are finally removed, and the medical staff retreat in disgust.

The Invaders: A haggard woman (Agnes Morehead) hears a strange sound on the roof. She climbs up to see a miniature flying saucer and tiny spacemen who invade her home. Their small ray guns sting, but she fights back.

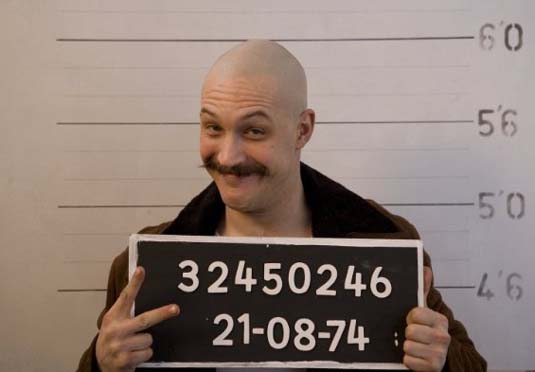

Shadow Play: Adam (Dennis Weaver) is on trial, and the judge gives him the electric chair. Adam chortles that it’s all a joke, a recurring nightmare in which all the participants are bit players in a scripted play. But will anyone listen?

The Obsolete Man: Romney (Burgess Meredith) is a God-fearing librarian in a totalitarian state in which books and religion have been banned. Romney is judged obsolete by the government chancellor but is granted several requests before he dies. He chooses to have a television audience watch his execution. Forty-five minutes before he is to die, he invites the chancellor to his room and locks them both inside.

Nightmare at 20,000 Feet: Robert (William Shatner) boards an airplane after having been discharged from a mental hospital for a nervous breakdown. He looks out his window during the flight and sees a weird creature on the wing. Alarmed, he alerts others. However, when they look out, the creature disappears. Robert eventually realizes that what he sees is a demon trying to dismantle the plane so it will crash. Robert decides to act.

Living Doll: Erich (Telly Savalas) is angry at his wife for buying his stepdaughter an expensive doll. Erich has a nasty disposition and soon discovers that the doll has a life of its own and it dislikes him. In fact, the doll tells him so. Talky Tina says emphatically “I hate you” and “I’m going to kill you.”

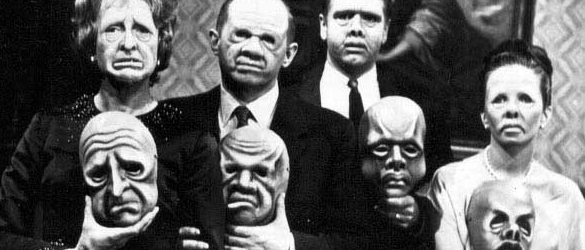

The Masks: On his deathbed, Jason Foster calls his four heirs to his side on a Mardi Gras evening. Each heir has a character flaw—self-pity, avarice, vanity or cruelty. Foster demands that each wear a mask he has fashioned for them. If they refuse to keep the masks on until midnight, they will be disinherited. The masks are hideous, and the heirs do not want to don them. But out of greed, they slide them onto their faces.

It’s a Good Life: Peaksville, Ohio, a small community, has been “taken away” from the so-called normal world—ravaged by 6-year-old “monster” Anthony (Billy Mumy). By mere thought and/or wishes, Anthony can make things and people disappear or turn into hideous creatures. All of the adults kowtow to his every desire.

To Serve Man: The Kanamits—nine-foot-tall, large-headed creatures—come to Earth from outer space, bringing gifts, spouting peace and promising to end famine. After some initial resistance by earthlings, the world relents and humans become entranced by the visitors. However, government agent Mike (Lloyd Chambers) soon discovers a sinister and shocking plot being hatched by the Kanamits.

“Everything leads us to believe that there exists a spot in the mind from which life and death, the real and imaginary,” writes surrealist Andre Breton, “the past and the future, the high and the low, the communicable and the incommunicable will cease to appear contradictory.”

To paraphrase Rod Serling, no tickets are needed to enter The Twilight Zone. All one needs is imagination.