A fantasy football decision, a choice made to appease the clamoring league of diehards that wanted a public execution – and wanted it now – was threatening to destroy the presidential campaign of Lawrence Fish.

Fish had headed that fantasy league, and as commissioner, he had given into popular demand. He had built the stake and burned the guilty party. The diehards had cheered with gusto, and Fish slept well.

That was twenty-five years ago. Fish, since then, hadn’t paid five minutes of thought to the league of friends, family, and random fantasy assassins who swept in and snagged a league title every few years.

That was back when people had Internet access. They still do, of course; just not many who can pay a dollar per click.

Lawrence Fish, after four years in Maryland’s House of Delegates, entered the 2036 Democratic primary as a nobody, an also-ran, as talking heads described the spindly six-foot-five white guy with a flop of hastily combed brown hair and a suit three sizes too big.

The three Democratic frontrunners had been selected and vetted by the Republican National Committee for Jesus and Prosperity.

The contest was still dubbed the Democratic primary for tradition’s sake. There was no real Democratic Party anymore, not since the government had shut down the Democratic National Committee for un-American behavior, the country’s few thousand remaining union members were given a three-square-mile reservation on the North Dakota-Canada border, and eighteen states in the South and Midwest had passed laws forbidding candidates to run as Democrats.

You ran as a Republican in those states, or on the side of the ballot labeled Terrorist.

For a decade, it had been illegal to even capitalize democrat or democratic.

So no one paid much attention to Lawrence Fish as he won the hearts and minds of the couple hundred people who would wear disguises and show up at local high school gymnasiums to listen to candidates who couldn’t possibly garner more than a tenth of the national vote in the following year’s general election.

Even if Fish or some other non-Republican stumbled into the White House, they’d be stymied at every turn: The House had a grand total of seventeen non-Republicans, and the Senate had had a ninety-ten Republican advantage since Obama – whose name was a federal crime – lost in 2012.

But Fish kept showing up at cold gyms and neighborhood playgrounds, where candidates would debate taxes and war and immigration in windstorms, hard rains, and boiling heat. It was the same argument as it had been for half a century: Are there any new ways to cut taxes and defend the homeland? The one-percent tax rate on top earners wasn’t low enough, the non-Republicans quibbled – there needed to be some relief, some way to unburden the job creators and lower the unemployment rate under thirty percent for the first time in two decades.

A plan that would have the unemployed working on the estates of millionaires in exchange for room and board was gaining traction.

That’s when – with a hundred people huddled in a backyard near Baltimore – Lawrence Fish interrupted a candidate who argued that public school teachers should work for free if they really loved their jobs. Fish stood up and blurted, “Jesus hates rich people.”

A hush swept over the huddled crowd. Lawrence Fish felt lightheaded, and he knew, in that instant, that he had spoken a great truth.

He had never had the thought before, never discussed it with the intern he lugged around to debates, never tested it with working-class people who scurried to campaign stops donning dark glasses and fake mustaches, hoping to remain unnoticed if not informed.

But Jesus, over the past few decades, had become America’s mascot. He was on the presidential seal now – a harshly angular jaw traced with a light beard, wavy sandy blond hair falling down onto two muscular shoulders, neck muscles bulging. Jesus’ sculpted arms, in the middle of the presidential seal, were crossed, and he looked at Americans with a stern face.

“In God we trust” had been replaced by, “The first will be first.”

The White House had built an office for Jesus Christ. No one was allowed in the office, and a White House guard was placed at the door twenty-four hours a day in case a policy paper or legislative proposal penned by J.C. himself was slipped under the door.

A fifty-foot Jesus statue had been erected in the middle of the New York Stock Exchange. The Son of Man wore a finely tailored power suit and clutched wads of cash in both hands. He had a bulge in his trousers and a cigar the size of an economy car in his mouth. Every once in a while, after a big day when stocks catapulted beyond previous all-time highs, Wall Street magnates would light the cigar and watch Jesus puff away.

Jesus had more political power than anyone, so tying him to a slogan made sense. A moment after Lawrence Fish said it – “Jesus hates rich people” – the crowd gasped, and three candidates fell to their knees and begged God to strike down Fish where he stood.

Fish held his breath. When death did not rain down from on high, he repeated the phrase. People muttered to one another, so he said it again, raising his voice for the first time in his adult life. A few onlookers clapped. Fish was surprised by their energy – many likely hadn’t eaten more than a meal a day for most of their lives, and their faces were hollow and worn, being among the seven in ten Americans living in poverty.

Someone yelled Fish’s slogan, and he yelled back. Soon they were chanting, and the crop of candidates was last seen running as one horrified unit back to their limousines. Lawrence Fish stood alone among the people, the voters, and they scream-chanted in unison, “Jesus hates rich people!” They hoisted Fish onto their weak, malnourished shoulders and carried him around the run-down playground.

Someone – a Republican plant, Fish later learned – had filmed the whole impromptu rally on her phone, and American Supremacy Network, the only television news outlet permitted by the Constitution, broadcast lanky Lawrence Fish raising his fists and hollering, “Jesus hates rich people!”

The news anchor, choking back tears, said, “This is the kind of tragedy that makes you wonder how our country has survived and thrived through all these wonderful years.” She wiped a tear from her high cheekbone. “May Jesus rip this man’s fucking head clear off.”

ASN military analysts discussed ways to carpet bomb Maryland, to kill Fish’s poison before it spread. Political experts told the ASN audience that the last anti-Jesus president had been a Muslim communist, forgoing utterance of his name for fear of four to six years in a federal penitentiary.

ASN ran with the “Jesus hates rich people” footage for almost three days on a continuous loop.

And as Lawrence Fish suspected, it worked. High school gyms were half full, then filled to capacity, and within two weeks of his playground declaration, Fish spoke to people in cavernous shuttered warehouses. Thousands showed up. Fish was hoarse from screaming his message to the hungry people in the very back.

“Jesus hates rich people!”

The warehouse crowd cobbled together a few thousand dollars from neighbors, and Fish’s intern made two thousand “Jesus hates rich people” T-shirts. People made their own after a while, and after Fish declared himself the winner of the Democratic primary, “JHRP” T-shirts could be seen at any diner, on any street corner or gas station anywhere Fish campaigned.

Then, one balmy October morning three weeks before the presidential election, ASN interrupted every show on television with what the anchor called “a national security alert.”

The words, “National Security Alert,” dripped blood in the corner of the screen.

“We’re getting word that an attack may be launched against the president on Election Day, when millions of Americans are projected to cast their votes against him,” the anchor said breathlessly. “A new poll shows the Jesus hating candidate, Lawrence Fish, leads by two percent.”

Fish told his intern to expect the worst. He meant assassination, of course, and in hindsight, he hoped for it. What the Republican National Committee for Jesus and Prosperity did next, Fish could never have prepared for.

“He kicked me out and said he wanted an all-white league,” the elderly black woman said from the podium on the White House steps. Lawrence Fish squinted at the television and knew exactly who it was. He massaged his temple and wished to be black bagged.

The hunched-over black woman sobbed and pointed at the cameras. “If you’re out there, Lawrence Fish, I hope you didn’t think you could run from your bigotry.”

The fantasy football league: A collection of twelve people who were not sustained by food and water, but by statistics. Fish had been commissioner for five years, and had strove to keep some semblance of gender parity. He made sure, at the start of every year, that at least two women were among the twelve fantasy footballers. More than anything, Fish wanted a woman to stream roll the league, take the title, and change the pig-headed minds of male league members who said fantasy football acumen came complimentary with their genitals.

It was the day before the 2011 fantasy draft when Marlene Robison asked to play. Fish awarded her the league’s only open spot. Marlene didn’t show up on draft day. Then she didn’t set her lineup for the first week of the season. Her roster had remained unchanged into mid-season, and at the behest of email rants from league members who said Fish should’ve never had women in the league in the first place, Fish replaced Marlene Robison with a friend of a friend – a guy.

Marlene, it turns out, had left a trail of Facebook rants on Fish’s wall, and after ASN anchors explained to the audience that Facebook was a popular site on the Internet – which was now accessible to only a sliver of the U.S. population – the network printed the digital trail for all to see.

Marlene had said Fish couldn’t handle a “strong black woman” in his fantasy league, and that he wanted a league “of white people, by white people, for white people.”

The president rubbed Marlene’s back as she bawled into the microphone, “I was the victim of racism, and the perpetrator was Lawrence Fish.” She hugged the president and turned back to the cameras. “Jesus doesn’t hate rich people, Mr. Fish. He hates you because you hate black people!”

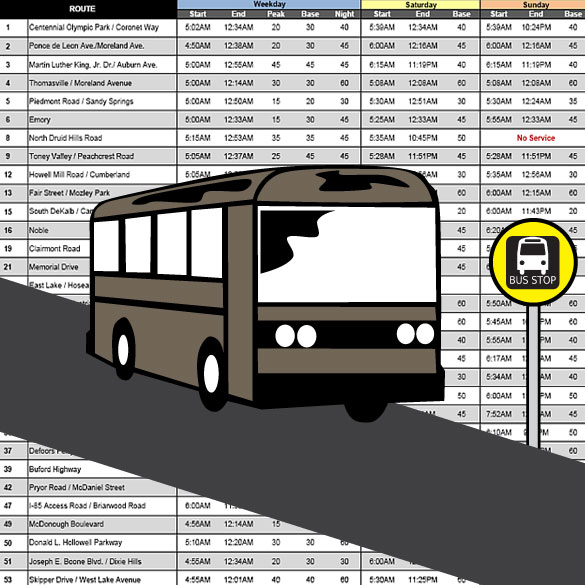

A day later, “Jesus doesn’t hate rich people. He hates Lawrence Fish because he hates black people” T-shirts were seen everywhere, dispatched from military planes flying over cities and suburbs across the country. Half of the Republican National Committee for Jesus and Prosperity’s ten million employees distributed “Jesus doesn’t hate rich people. He hates Lawrence Fish because he hates black people” shirts, hats, bumper stickers, and car flags at intersections, bus stops, office parks, golf courses, churches, grocery stores, and fast food restaurants from coast to coast.

Lawrence Fish needed a defense, and even if ASN was constitutionally bound not to broadcast anyone who didn’t carry a Republican National Committee for Jesus and Prosperity ID card, at least he could bring a friend from the old fantasy league to his campaign stops, which now drew tens of thousands.

Fish called his friend of forty years, Arne Tyler.

“They gave everyone ten mil a piece to shut up and go away,” he told Fish. “Me, Jason, Bryan, Victor, Patrick, Andy – even Billy. Set us up for life.” Two league regulars had died, so that left one fantasy owner Arne hadn’t named.

“What about Evan?” Fish asked.

“Said no to the cash, actually, so they shipped him off to the war in Toronto,” Arne said. Toronto had been under siege for going on a decade. It was the last place on the planet that offered universal health care, so America had launched its War for Patients’ Rights. “Poor geezer probably doesn’t even know where he is.”

Arne invited Fish to come live with him in Florida, which had fifty square miles of dry land left.

“That’s okay, Arne,” Fish said. “I have to run for president now.”

The grind continued, from one campaign stop to the next. It was after Fantasyfootballgate that the throngs took on a distinctly whiter, fatter tone. Lawrence Fish’s campaign crowds had been mostly brown and frail – at some stops, he was the only white guy.

Now, since Marlene Robison’s tearful diatribe, the crowds had a lighter hew.

They came to the campaign stops and stump speeches not dressed in the Republicans’ “Jesus doesn’t hate rich people. He hates Lawrence Fish because he hates black people” shirts, but in shirts, sweatshirts, and jackets that read, “Lawrence Fish: Of white people, by white people, for white people.”

They stood silent while Fish shouted his populist message: Raise the top tax rate to ninety percent. Free health care for every non-millionaire. Free Internet for everyone. Pulling troops out of all nineteen wars America waged across the globe. The death penalty for industrial polluters. Renaming the American Supremacy Network, and calling it News Station. People whooped and hollered, like they had for a year.

Fish finished, the crowd in a frenzy, with his signature line: “Jesus hates rich people!”

Fish’s new white, well fed supporters looked bored, like they were waiting for the band to play its radio hit because that was the only song they knew.

Fish scanned the throng and knew this was his chance to undo what Marlene Robison — that neglectful fantasy football owner — had done.

“And to my new supporters out there,” Fish bellowed, “Marlene Robison was right!”

Purposefully vague, Fish hoped not to alienate his base while roping in the “of white people, by white people, for white people” crowd. The lighter-skinned, plumper, richer parts of the crowd broke into hysterics.

“He’s the real deal!” Fish heard a white lady scream, and drop to her knees. Tears gushed down her face. “He’s our guy!”

Four days later, on a ninety-degree November Tuesday in Baltimore, Lawrence Fish watched lines of voters wrap around precincts. ASN reported that voter turnout in 2032 had been just over twenty percent. The 2036 election was expected to draw eighty percent of American voters.

“An electoral firewall in defense of the president and his closest adviser, Jesus,” the ASN anchor described the scene.

Fish watched, first on television, then discreetly from a distance as voters bombarded an elementary school, and saw a stream of alternating T-shirts. Sandwiched between the voters sporting their “Jesus hates rich people” shirts were smiling groups of white people, their chests emblazoned with the phrase Marlene Robison had coined: “Lawrence Fish: Of white people, by white people, for white people.”

The two sects of Fish supporters mingled in line. Fish smiled when a voter who despised millionaires held the door for three voters who loathed minorities.

Fish stood there, leaning his frail frame against a tree at the edge of the school parking lot, and smiled. He thought of the old fantasy league. He had tried to run it with with respect for everyone, and a preference for fantasy’s underrepresented groups, like Marlene Robison. But he had known — even in his mid-twenties, with no leadership experience past sixth-grade class president — that the league’s monsters must be appeased, because without the monsters, there was no league. If they had reason to demand the death penalty for an unworthy, undedicated fantasy owner, Fish had known he must dole it out.

Fish understood that if he was ever going to inspire changed hearts and minds, he had to be commissioner. And if that meant the occasional partnership with the monsters and diehards, so be it.

The fantasy football league had dissolved with eleven mostly angry white men. Lawrence Fish had failed his social experiment.

He hoped this would be different — being president, striking a balance, appeasing the monsters — and as he thought of these things and leaned against a tree with his arms folded across his bird-bone chest, he felt cold metal press gently against the nape of his neck.

—-

Between his full-time job as an education reporter in Washington, D.C., and his freelance gigs for local magazines, C.D. Carter has written tales of the macabre for a host of publications, including Dark Moon Digest, Flashes in the Dark, SNM Horror, Static Movement, Lost Souls Magazine, and Death Head Grin. Much of Carter’s short-story horror is based on the life of a journalist in the city. Carter credits his wife, Melissa, for green-lighting his best ideas, and telling him which stories should be buried and left for dead.