How long does an art experience or observation last? One painting, maybe can last a few minutes as you stand in its grace with contemplation before moving on to the next piece. A sculpture may last slightly more, as you circle for perspective to unlock its meaning and find interpretation. Modern art, depending on its form, can be an immersive encounter that moves through various mediums, yet its engagement still only lasts a short while. The observation of art is a fleeting experience, for connoisseurs and academics the impact can be longer, but for the average art lover and gallery goer, art can be a fading encounter. Film on the other hand, taken as an art form, can last from eighty minutes and beyond, as the film’s contents and narrative sink in, its impact after viewing can be immeasurable. Its form and perception is in constant motion, scenes within are placed under

constant scrutiny, its interpretation is always changing. Yet because film also falls in the category of entertainment it is rarely seen in the same artistic light as a painting or a sculpture, except if it is categorized as an art film. This, I believe, is an incorrect assumption. Film has an opportunity to reach a much broader and wider audience then traditional art forms, and its collaborative form means that many artistic individuals contribute to the final piece. Throughout film’s short history it has attracted artists of more traditional forms, who have used the medium to explore their vision to greater affect. From Salvador Dali to Andy Warhol, and in more recent years modern artists like Steve McQueen (Hunger, Shame, 12 Years a Slave), Miranda July (Me and You and Everyone We Know, The Future) and Sam Taylor-Johnson (Nowhere Boy and the forthcoming adaptation of Fifty Shades of Grey) have produced compelling films that blur the line between art and entertainment. If we accept that these films are part of an artist’s body of work then, unlike the majority of the other artistic mediums they have produced in, we can take ownership of their film work in a more accessible way.

When an art collector buys a painting or inclusion in their personal collection, it belongs to them for a period of time, they become the custodian of the piece, taking care of it until it eventually outlives them and moves on to another owner or becomes acquired by a galley for public display. Whilst in that collector’s possession, the piece looses the diverse interpretation that is recognized via public spectatorship, and is now only defined by one individual. Of course there is always prints and even expert forgeries that allow for an audience to still observe and experience the piece in some way, but the original is, for the time being at least, absent from the public sphere. Because film has no physicality as such, its ownership by an audience is allowed through the sale or rental of DVD copies, cinema and television screenings, and now digital downloads and online streaming, that permit the film to be shared with a potential audience of millions. We can own a copy of the film in these formats, but the original reels, or digital files, are left to disintegrate and decompile. Even ownership of these ancient reels never allow true ownership, because copies are already available throughout the world. Furthermore, the rise of digitally made films has meant that ownership by the director or production team is now completely invalid as digital files are shared online and jump from one hard drive to the next in a constant exchange of data.

In artistic timelines, film is still in its infancy, yet we have almost plundered its current resources. We have moved into the digital realm with such haste and need to produce spectacle, that the original, artistic endeavour has been lost to us. Nevertheless, as we approach this pinnacle, a new possibility awaits us. The use of interactive digital technology that allows users to guide and influence a timeline, producing many different possibilities and outcomes is also in its infancy. So far this has been explored in basic form in music videos (often a breeding ground for new and innovative technologies that have been applied to filmmaking), such as promotional videos for the Canadian rock band Arcade Fire’s singles “Neon Bible” and “We Used to Wait”, both using interactive technology to produce a unique experience. One day there could be a possibility that this will be applied to a mainstream film, allowing audiences to engage and produce a narrative timeline that is different and distinctive to an individual. If and when this happens, will we have finally achieved our full individual ownership of film? The elements that need putting together for a individual experience have still been created by a filmmaker, complete ownership is still out of our reach.

However, film audiences are now wanting to become even more involved and participate in the initial production of a film, in order to claim ownership. Two films recently, which, as of writing, have only just started full production, were the subject of much internet criticism, due to casting decisions made by the film’s producers. The forthcoming Batman vs Superman (scheduled for a 2015 release) became a hot topic when it was announced that actor and director Ben Affleck would be taking over the role of Batman from Christian Bale. The criticisms that were aimed at Affleck were harsh to say the least, and as he had yet to even don the Batman outfit or read one line of dialogue, duly unfair considering his experience as an actor and also acclaimed director of Gone Baby Gone, The Town and recently Argo, an Academy Award winning film. The forthcoming adaptation of E.L James’s

immensely popular S&M themed books Fifty Shades of Grey Trilogy was the subject of an internet campaign by fans insisting on their preferred actors to take the lead roles of the innocent Anastasia Steele and the wealthy domineering Christian Grey. Fans of the trilogy petitioned for Gilmore Girls actress Alexis Bledel to take the role of Anastasia, whilst the favourite for male lead seemed to fall on Ryan Gosling. Despite neither of them being approached to play the roles, the fans insistences seemed more like demands. When the lead actors were announced (Dakota Johnson and Jamie Dornan), the collective disappointment seemed to overwhelm the future success of the film.

This rudimentary audience participation in a film production could be seen as a step towards a call for a democratic inclusion in the future of film. For almost a century, film studios, producers, and film directors have bestowed their vision upon us. Never has an audience actively participated in the process of casting decisions, which film stock to use, which director and production team best suits the material, which cinemas the finished film should play in. Even the film, which is considered the best of the year, or has the best technical qualities, is judged by film academy insiders who proclaim their evaluation sound and in no way incorrect, yet often the decision is up for debate from film critics and audiences who get no say. As the world calls for more freedom, democracy and social justice, and an end to bureaucracy and inequality, we should look to film as an apparatus for change and reflection of our society. Perhaps the best way to claim ownership over film is to demand films that offer insight and intelligence, and abandon the spectacle and propaganda of mainstream

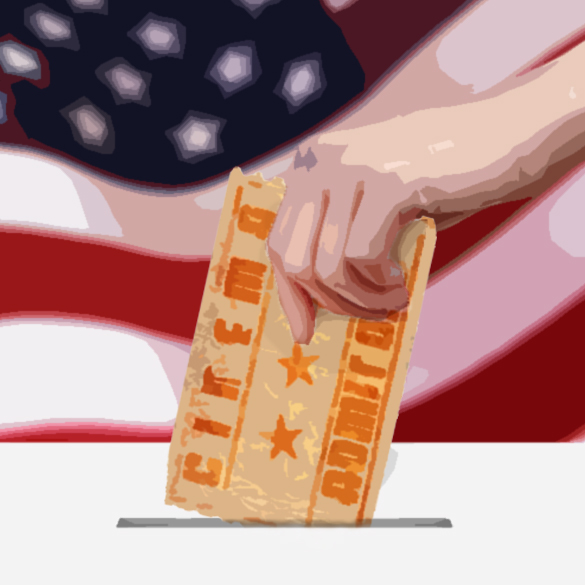

Hollywood productions. We should insist on better access to the type of films that do promote change and expand on new ideas. The way that we can make this change and refresh the mediocre cinematic landscape is by using the very backbone of democracy: that is voting. Not filling out ballots, or placing films in unjust and pointless competitions, but by taking the cinema ticket to the smaller, independently made, and provocative movies that do make it to cinema screens, and then taking it further by purchasing the DVD or streaming the film online. All this activity sends a message to the film producers that as an audience we demand the right to access film that says something realistic about who we are and where we are.

One thought on “Film and Ownership”

Comments are closed.