BY: GRADYFINGER

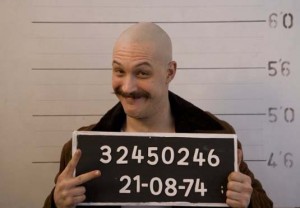

“You can’t pin me down.” These words, spoken by Charlie Bronson near the end of the movie of the same name (released in 2008), sum up how I feel about both the man and the movie. The movie, written and directed by Nicolas Winding Refn, is based on the true story of Charlie Bronson (born Michael Gordon Peterson), who in 1974 robbed a post office of £26.18 and stretched his seven-year sentence to thirty-seven years in prison, thirty-three of which were spent in solitary confinement. The movie follows Bronson from infancy (behind the bars of his crib, being watched by his parents) into adolescence (beating up his teacher and other students), but mostly focuses on his adulthood behind bars and the reason in which petty theft lead to a lifetime of solitary confinement.

The film opens with the line, “My name is Charles Bronson and all my life I wanted to be famous.” This is essentially the main premise of the movie: a man so compelled to become famous that he set on a mission to become the most violent prisoner in England. Bronson goes on to explain that with little options for fame, he used his seven-year prison sentence as an opportunity. For him, prison became a place to “sharpen my tools, hone my skills.” Using his experience as a bare knuckle boxer (his promoter thought the name Charles Bronson was more suitable than Michael Peterson), Bronson instigated over a dozen hostage situations, rooftop protests, and repeated attacks on prison staff and inmates, resulting in the prison system having him “ghosted” (moved from prison to prison) over 100 times.

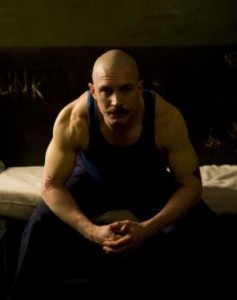

The film, however, isn’t your ordinary biopic. The narrative doesn’t follow convention and much of the movie is comprised of random scenes of a greased up, bloodied Bronson inciting violence to swelling classical music. There are some elements of the film that confuse me, mainly the homoerotic overtones. While I am certain Refn included these for a reason, it remains a total mystery to me. The script itself isn’t particularly mind-blowing, but Refn’s strength lies in his direction. There are very few scenes where the camera moves with the action. Most scenes, the camera is a close and steady shot of Bronson, as if he is imprisoned by the screen. We get a sense of the tight space of solitary confinement that Bronson has lived in for the bulk of his adult life. This film direction also gives us the sense that here is a man desperate to be watched.

The film portrays Bronson as a mastermind of drama and often his monologues are shown with him in a three piece suit on stage before an adoring audience. In some of these scenes his face is painted like that of a mime or a clown (Michael Peterson was a circus performer before he moved to bare knuckle boxing) and we see a man capable of extreme violence but also humour and charisma.

And here-in lies the movie’s strength (and a major dilemma for the viewer): we acknowledge that even when enraged, there is something charismatic about this man. We like him, want him to succeed. We applaud his verve, but we are also fearful of him, scared of his unpredictable nature. I believe this nuance was achieved through the brilliant performance of Tom Hardy (he also stole every scene in Inception). My husband asked, after viewing the film, if I thought the movie would have been so successful with another actor (Jason Statham was originally supposed to play the part, but couldn’t due to scheduling conflicts) and I think the answer is no. Hardy’s ability to arouse sympathy from the viewer is so good, the performance should be seen in the same league as Malcolm McDowell’s Alexander DeLarge (A Clockwork Orange) or Anthony Hopkins’ Hannibal Lecter (Silence of the Lambs). Tom Hardy’s performance is subtle enough to portray the conundrum of Bronson, a man prone to violence, humour and tenderness.

It is this tenderness and charisma, no doubt, that has spawned thousands of Charlie Bronson fans. There are numerous YouTube videos, petitions and websites demanding his release. His art (the movie used his original compositions) has won awards and was shown as part of ArtBelow, and LA designer Joseph Randle collaborated with Bronson to create Bronsonwear, street wear that uses Bronson’s artwork. Bronson supporters maintain that his lifetime prison sentence (given in 2000 after another hostage incident) is unjust, and even more unjust is his solitary confinement. They reason that he has not killed anyone and never been violent towards women or children. They argue that the prison system has intentionally baited Bronson into violence and there have been no efforts to rehabilitate him.

Bronson himself uses the same rationale for his actions. Bronson recorded a video statement that was shown at the movie premier, in which he says, “I’ve grown up, I’ve matured, I’m a different man, I’m now anti-violent. I’m anti-drugs, anti-crime, but I’m still held in a cage in solitary. I’m not a murderer, I’m not a rapist, I’m not a paedophile. I’m a hostage of my own past.” Since the premier, however, he’s had several more violent outbursts, the most recent in November 2010, when he buttered himself up and attacked six guards.

Murder and rape aside, the penal system is posed with a problem: what are they to do with an inmate who continually acts out violently, putting other inmates and guards at risk? Sure, he hasn’t killed anyone, but he habitually inflicts physical and emotional damage on other people. But Bronson and his supporters are right in another sense: does anyone deserve to be caged up in a tiny space, without any efforts of rehabilitation?

The film isn’t really successful in addressing these problems. Nor is it concerned with the why and how Peterson became so violent, except to chalk it to his desire to become famous. The film is correct, in a sense, that Bronson has been opportunistic. He’s published eleven books, most notable is Solitary Fitness, about working out in small space. I’m not sure if I believe in the main premise that Bronson was a public relations mastermind, a classic narcissist who used his circumstance as an opportunity for fame. But regardless of who Bronson really is, the film is right, butter or no butter, you can’t pin him down.