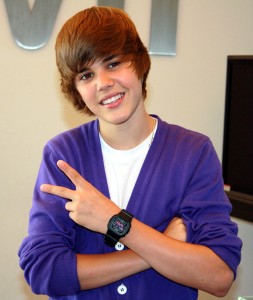

He’s the sixteen-going-on-seventeen year old Canadian heartthrob who won 19 awards –and the hearts of millions of tween girls – in 2010 alone. He’s the from-Youtube-to-Grammy’s success story that every budding musician longs to be. He’s the first artist since the Beatles to share not only their level of fame but also their characteristic mop-top.

He is, of course, Justin Bieber. And if you didn’t know that, you’re the only one out of six billion people on this earth. For those who are increasingly frustrated by the level of media coverage on a boy who has yet to hit puberty in any real way, there is some good news. It appears that Microsoft Word’s “Spell Check” function has yet to recognize “Bieber” as a legitimate word, in contrast to its disquieting recognition of Facebook (though it does, in explicit defiance of Zuckerberg’s commandment, mandate a capital “F”). But, with the exception of automated, pre-programmed software, it appears that no one can escape what has been dubbed “Bieber Fever” – a virus that shows no signs of slowing down.

are increasingly frustrated by the level of media coverage on a boy who has yet to hit puberty in any real way, there is some good news. It appears that Microsoft Word’s “Spell Check” function has yet to recognize “Bieber” as a legitimate word, in contrast to its disquieting recognition of Facebook (though it does, in explicit defiance of Zuckerberg’s commandment, mandate a capital “F”). But, with the exception of automated, pre-programmed software, it appears that no one can escape what has been dubbed “Bieber Fever” – a virus that shows no signs of slowing down.

And yet, despite gracing the cover of every magazine from Tiger Beat to Vanity Fair, from Seventeen to People to Billboard, Justin Bieber remains, at least in any critical way, unexamined. We all know Justin Bieber got his start when his mother, Patricia Lynn Mallette, began uploading his videos on YouTube. We all know that he got “snubbed” (if you can call his deserved loss to lesser-known but infinitely more talented 23-year-old Berklee College of Music professor and jazz bassist/vocalist Esperanza Spalding a snub) by the 53rd annual Grammy Awards. The fashionistas out there are acutely aware that his “swagger coach,” 20-something Palm Beach resident Ryan Good, insists on dressing him like a miniature, white version of Randy Jackson, what with the casual tossing of the peace sign, the obnoxiously colored, buttoned cardigan, and the over-sized wrist jewelry. But start to mention anything outside of YouTube –including his discovery and subsequent undercover reinvention by Scooter Braun, an industry veteran also responsible for one-hit mega-wonder Asher Roth – and people begin to get a little hazier on the details. All anyone wants to talk about (aside from his helmet haircut and rumored link to 18-year-old Miley Cyrus wannabe Selena Gomez) is how Justin came from nothing and how his fans – and only his fans – single-handedly brought him the fame and success he now enjoys.

Perhaps the triad of brown-haired girls, featured almost exactly half-way through the official trailer for Bieber’s documentary “Never Say Never,” said it best. Decked out in a white tank and a bright pink, feathered boa, one of the tweens explains, “He’s such an inspiration, he came from such a small town…it gives us hope.”

The documentary itself, which hit theaters on February 11 and grossed over $12.35 million the first day (around $30 million its first weekend, putting it at a solid number 2 at the box office), harps on this self-made quality of Bieber, something that it seems everyone around him is intent on defending. The Bio section of Bieber’s YouTube channel, kidrauhl, insists that “he is light years ahead of his manufactured pop peers.” In fact, the comparison between Justin and those produced by the “Disney Machine” pervades contemporary discussion on the young phenom. Even Usher (Bieber’s self-proclaimed “Big Brother”) has placed Bieber in explicit contradistinction from those artists, like Miley Cyrus, the Jonas Brothers, and others, who have been “manufactured” by big business.

But is there really a difference between the Disney Machine and the Def Jam Machine (Bieber’s current record label), which also pumped out Lady Gaga, Ra Rule, Jay-Z, Christina Milian, Kanye West, Young Jeezy, TLC, Mariah Carey, LL Cool J, Ludacris, Jennifer Lopez, Ne-Yo, Nas, Rihanna, Redman, The-Dream, and the Beastie Boys? While everyone is touting Bieber as the paradigm of self-made success, they are ignoring the fundamental question: exactly how is it that Justin’s YouTube went from showcasing his singing in a talent competition in a local school to, all of a sudden, an official “One Time” music video? Who is really behind the uploads – the original ones, and the ones of infinitely higher quality that have sneakily come to replace the originals? Is Bieber really as organic as his marketing team claims he is, or is he and his story of fame just as artificial as the stories of his Disney peers?

There is no doubt about it – Justin was discovered on YouTube, which is itself an accomplishment. Out of the tens of millions of wannabe rappers, singers, and dancers, he stood above the pack because of his unique combination of raw talent and natural stage presence, even from a young age. But merely being discovered on YouTube does not automatically generate the sort of international fame Justin subsequently received. Esmee Denters, a native of the Netherlands, was similarly discovered through YouTube (in her case, by Justin Timberlake), and yet she, despite her husky voice, Hollywood good looks, and promotion by Timberlake’s company, never quite made the big time. Either there is something about Justin – some inexplicable, inescapable star quality that permeates the air around him – or something about his promotion that made the real difference.

Justin’s staged appearances, overly stylized outfits, and suspiciously increasingly well-produced “home videos” seem to hint at something deeper behind the young phenom – something calculated. If Justin is truly successful solely because his YouTube fans catapulted him to fame – because their voices were so loud they could no longer be ignored—it begs the question as to why he changed so dramatically in his appearance and behavior. Why the homage to the Beatles through his haircut, and why the sudden change in haircut the moment all 16-year-old boys started catching on? As Scooter Braun, the man who discovered Bieber and who currently serves as his manager, revealed to Dan Schawbel, a personal branding guru, “If you find a video online of Asher Roth and Ludacris, you’ll see a little kid sitting behind them during their conversations. That’s Justin Bieber at thirteen. That was when I started developing him.”

“ When I started developing him [emphasis added]”? Some language for an organic, fan-made prodigy. The marketing strategy appears to be more focused on convincing fans that they were the root of his fame, rather than actually making them the root. Braun also admits that Bieber didn’t achieve fame in a short period of time; rather, “We built his YouTube channel over three years.” Far from being the postings of a loving and doting mom, it appears Justin’s channel itself was directed by an experienced marketing guru, something Braun admits, saying “I’m filming half of those videos you see online.”

Rather than actually being organic, the secret to the marketing was to make it appear organic. “Don’t overproduce the videos,” Mr. Braun argues. “Don’t try and put in special editing.” In other words, be strategic about not being strategic. Market by pretending not to market.

The real question, then, is why this is the strategy that works. Successful marketing strategies provide valuable insights into the culture of our nation. What appeals to us, at our core? What stories are we looking for? What influence do we seek to have? The fame of Justin Bieber tells a story greater than a something-from-nothing, rags-to-riches tale; it has more lessons than merely how to promote other potential stars through the internet. At its core, the fame of Justin Bieber tells us what it is we are looking for as Americans, and what idols we seek to create for ourselves.

In Justin’s case, it appears we’re sick of the mass-produced, corporate-driven creations the likes of Miley Cyrus, Demi Lovato, and Selena Gomez. Sure, the truth of the matter may be that Justin was marketed with much the same level of thought and inquiry as any of his Disney peers, but equally important as the truth is the perception of that truth. Braun tapped into something deep and intrinsic within young Americans, who have seen the world spiraling into violence, disarray, and recession and have no way of fighting it. Justin gives them a voice. As Braun’s marketing strategy ensures, kids are convinced that it is because of their voice, because of their tweets, posts, and texts, that Justin is where he is. They feel a deep sense of connection with him, because they feel responsible for his success. Every time Justin sells a record, his fans feel his success. As Braun points out, “And in a recession, the last thing people want to hear about is entitlement. They want to hear about hard work, a successful story and “The American Dream.” And funny enough that “The American Dream” came from some kid in Canada.”

So maybe something Bieber shares with the Beatles is more than just a haircut, more than just excessive fame. Maybe he shares the message of the Beatles – to keep hope alive, and to make tweens, teens, and young adults, so often overwhelmed by their seeming irrelevance to world affairs, feel like they can make a difference – even if that difference just means propelling someone else to fame.