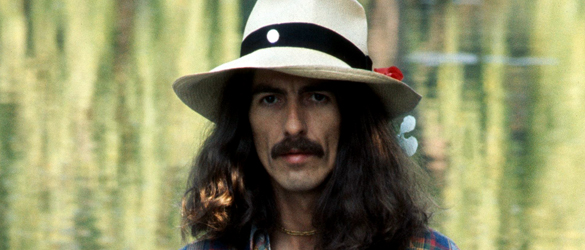

“Sometimes I feel like I’m actually on the wrong planet, and it’s great when I’m in my garden, but the minute I go out the gate I think: ‘What the hell am I doing here?’”—George Harrison

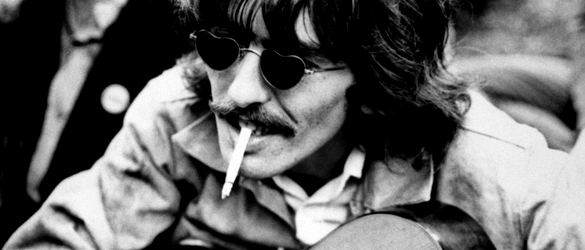

By the time he was 21 years old, George Harrison—along with John Lennon, Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr—had conquered the pop world. Within a few years, when the so-called “Summer of Love” swept over the world, the Beatles had invaded Western consciousness to a degree unmatched before or since. In June 1967, the Beatles released their legendary Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album to worldwide acclaim. As author Langdon Winner remarked: “The closest Western Civilization has come to unity since the Congress of Vienna in 1815 was the week the Sgt. Pepper album was released.”

However, while the world was captivated with the Beatles, the foursome was less enchanted with life in the fishbowl. George, the so-called “quiet one,” was so bothered by the trappings of fame that he began to disentangle himself from the group. As he explained:

The mania side of it started happening in 1963, when we began touring seriously in England. And then we did some tours around Europe, and I think it was because of the mania that was happening then that the Americans caught on—they did features on us in Time and Life and Newsweek. That set us up for the trip to the USA in 1964. The mania got to me in 1966, and around that time I got a bit tired of what they call the adulation. I’m still not that keen on that side of it. It’s nice to be popular. It’s nice to be loved. But it’s not so nice to be chased around and on the front page of the paper every day of your life, with people climbing over the wall all day long.

In fact, in later years George seemed determined to leave his Beatle past in the past. As his son Dhani remarked:

My earliest memory of my dad is probably of him somewhere in a garden covered in dirt, somewhere hot, a tropical garden, in jeans, khakis covered in dirt just continuously planting trees. I think that’s what I thought he did for the first seven years of my life. I was completely unaware that he had anything to do with music. I came home one day from school after being chased by kids singing “Yellow Submarine”, and I didn’t understand why. It just seemed surreal: why are they singing that song to me? I came home and I freaked out on my dad: “Why didn’t you tell me you were in The Beatles?” And he said, “Oh, sorry. Probably should have told you that.”

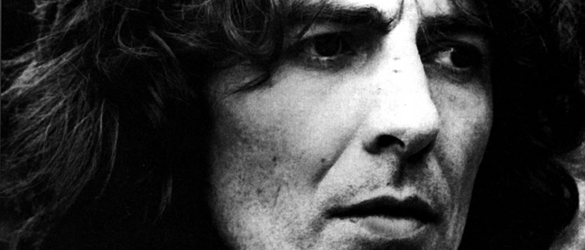

George’s nonchalant attitude about his near-mythic experiences as a Beatle was indicative of his overall approach to life, one shaped by his own human frailty, the ambiguities of life in general and his keen spirituality. “He was at odds with himself,” writes author Paul Theroux, “but who isn’t? In that respect—‘living proof of all life’s contradictions,’ as he put it—he resembles most of us. We recognize him as a kindred soul in his contradictions—and though his life was lived on a vast scale, he was unusually truthful, and in his songs much more explicit than we dare to be. He made it his mission to explore his contradictions in his own way, through his music.”

“He had karma to work out,” his wife Olivia said of George. “[H]e wasn’t going to come back and be bad. He was going to be good and bad and loving and angry and everything all at once. You know, if someone said to you, ‘Okay, you can go through your life and you can have everything in five lifetimes, or you can have a really intense one and have it in one, and then you can go and be liberated,’ he would have said, ‘Give me the one, I’m not coming back.’”

![]() Olivia Harrison’s fascinating book George Harrison: Living in the Material World (Abrams, 2011), published in conjunction with Martin Scorcese’s two-part HBO documentary, takes readers on a visual and archival journey of Harrison’s life pattern. Drawing from Harrison’s own photographs, letters, diaries, and memorabilia, Olivia traces George’s life arc from his boyhood in Liverpool through the Beatle years to his discovery of and eventual conversion to Hinduism, his later interest in film producing and as an independent musician, and finally his years as a recluse and avid gardener.

Olivia Harrison’s fascinating book George Harrison: Living in the Material World (Abrams, 2011), published in conjunction with Martin Scorcese’s two-part HBO documentary, takes readers on a visual and archival journey of Harrison’s life pattern. Drawing from Harrison’s own photographs, letters, diaries, and memorabilia, Olivia traces George’s life arc from his boyhood in Liverpool through the Beatle years to his discovery of and eventual conversion to Hinduism, his later interest in film producing and as an independent musician, and finally his years as a recluse and avid gardener.

With quotes from Paul McCartney, Ravi Shankar, Eric Clapton and others, Harrison’s intriguing sojourn in the material world is laid bare before our eyes, revealing a complex character who confronted the reality of a world gone mad. Indeed, George’s sense that all was not well with planet Earth was not only reflected in his music but spurred him to create a sanctuary out of his gardens, hiding him from the world and keeping the world from him. “[I]t’s great when I’m in my garden, but the minute I go out the gate I think: ‘What the hell am I doing here?’”

What George was doing was simply trying to be the best person he knew how to be, whether that pertained to his music, his spirituality or his relationship with the universe. As a guitarist, George spawned a generation of Harrison wannabes. According to Paul McCartney:

George was the best guitarist in the group. I mean, we were all pretty good, but George was lead guitar. John would take turns because John was good too. He had a more primitive style, but George was more technical, more practical, and we all thought he was a great guitar player. The nice thing was that he didn’t really emulate anyone.

Or as Eric Clapton puts it:

He was clearly an innovator: George, to me, was taking certain elements of R&B and rock and rockabilly and creating something unique. I had quite a lot of self-confidence going in my concept of myself as a sort of blues missionary, and I wasn’t looking for any favours from anybody. And George recognized me as an equal because I had a level of proficiency even then that he saw as being fairly unique too.

Harrison’s influence as a great musician is equaled only by his spiritual influence, which extended to his band members. It is difficult to imagine Lennon’s “Across the Universe” or “Instant Karma” or McCartney’s “Let It Be” without George Harrison. Even Ringo was impacted. “Over the years, I got to love the music myself and now I’m a Christian Hindu with Buddhist tendencies,” says Starr. “Thanks to George, who opened my eyes as much as anyone else’s.” And as Olivia Harrison recognizes in her book, George not only made great music but music with an amazing, uplifting spiritual message.

Nothing I can say about George speaks louder than his music. Knowing how reluctant he was to talk about himself led me to illustrate his years mostly in pictures. His life was fascinating not entirely by chance. He worked hard, was curious and energetic. He plunged into the heart of people, places and things he encountered, the good and bad. He claimed to be a sinner but never a saint.

Life to him was a quest for deeper meaning and everything was important to him but nothing really mattered. His particular way of embracing and dismissing life’s joys and disasters was completely disarming. He could let go as easily as I held on. ‘Be here now’ was repeated so often we actually did begin to live in the moment.

Time was shortened, stretched and often completely disregarded by his personal clock. At times he moved with the hours and days and then to the rhythm of heavenly bodies in the cosmos. So life was a blink of an eye, but eternal. When he sang, ‘Floating down the stream of time, from life to life with me’, he made parting so soon seem like waving goodbye for the afternoon.

Besides writing such great songs as “Something” (which Frank Sinatra called the greatest love song ever written), Harrison wanted to teach his listeners about the truths of eastern spirituality. From “Within You Without You” (which forms the center of the Sgt. Pepper’s album) to “Rising Sun,” George knew something most of us didn’t and still don’t: there is a reality beyond the material world and what we do here and how we treat others affects us eternally. As he sings in “Rising Sun”:

But in the rising sun you can feel your life begin

Universe at play inside your DNA

You’re a billion years old today

Oh the rising sun and the place it’s coming from

Is inside of you and now your payment’s overdue.

As Harrison explains, we can choose to do good or bad, but our present state of being in this world is controlled by such choices:

Although we do have control over our actions right at this moment, I think what we are now is a result of our past actions, and what we’re going to be is going to be a result of our present actions. So for certain things there’s no way out. There’s no way I wasn’t going to be in The Beatles, even though I didn’t know. In retrospect that’s what it was, it was a set-up. At the same time, I do have control over my actions. I can do good actions or bad actions.

Sadly, we human beings make a myriad of bad choices that result in pain and devastation. As George laments in “Isn’t It a Pity”:

Isn’t it a pity

Now, isn’t it a shame

How we break each other’s hearts

And cause each other pain

How we take each other’s love

Without thinking anymore

Forgetting to give back

Isn’t it a pity

Some things take so long

But how do I explain

When not too many people

Can see we’re all the same

And because of all their tears

Their eyes can’t hope to see

The beauty that surrounds them

Isn’t it a pity

George Harrison was 58 when he died from cancer on November 29, 2001. While he blamed his life-long cigarette addiction for his early demise, he was obviously traumatized by a knife attack in late 1999 from an intruder in his home who believed he was on a “mission from God” to kill George. Although Olivia fended off the assailant by striking him repeatedly with a fireplace poker and a lamp, Harrison suffered seven stab wounds and a punctured lung.

Harrison’s son Dhani, next on the scene, knelt by his prostrate father and was “immediately covered in blood.” The knife had left its mark on George’s thigh, cheek, chest and left forearm, as well as his lung. “He was drifting,” noticed Dhani. “I honestly believed he was going to die. He was so pale. I looked into his eyes and saw the pain. Dad kept saying, ‘Oh Dhan, oh Dhan.’ He looked even paler in the face, and he was groaning and saying, ‘I’m going out.’ He made little sense, and I knew he was losing consciousness. It was about ten to twelve minutes—although it seemed like a lifetime—before the paramedics arrived.”

Against all odds, George Harrison survived long enough to give us hope and preach love and peace on Earth. “From the day I met him he was defiant,” Olivia writes, “and so determined that nothing was going to stop him from leaping as far as he could.”

George Harrison, the Liverpool kid who survived Hitler’s blitzkrieg and the pressures of celebrity as a Beatle and found comfort in spirituality, left an amazing legacy. In the end, Harrison knew that a life lived well and with purpose can overcome the pain and travails of this world. As he sings in “Here Comes the Sun”:

Little darling

I see the ice is slowly melting

Little darling

It seems like years since it’s been clear

Here comes the sun

Here comes the sun

And I say

It’s alright.