Who was it that said the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation? I couldn’t help but wonder when after fourteen hours of straight driving (with frequent enough stops to relieve myself), I left the freeway and turned down his road. Looking around I could see that nothing much had changed since last time I’d been here.

Some places get stuck in time.

It’d been a long while since I’d driven down Misery Road. I pulled my old Dakota pickup into the parking lot of the country store on the corner, where Misery intersects with West Main. How people are born here, live and then die here is beyond me.

I never knew it was such a big world till I left.

When I walked in Myrna was behind the counter, and they were frying up eggs and bacon in the back. The place was buzzing with morning customers on their way to work, picking up their little egg and cheese sandwiches on English muffins that came wrapped in parchment paper, and getting some of that bad country coffee in those tall Styrofoam cups. There were those other early birds of a different type too, already coming around for their forties. These folks weren’t really going anywhere particular. Seemed to be a long-standing tradition around here; those little sandwiches with that bad coffee. And those forties.

And not going anywhere.

Myrna looked up at me and her eyes crinkled and her face wrinkled and she said, “Well I’ll be damned, is that you John Tucker?” She rubbed her eyes pretending feigned disbelief. “See? I told you you’d be coming back here, what California’s not treating you so well?” She giggled like a school girl, which she was not, and yelled to the back to the kitchen to no one in particular, “Hey you see this out here? That John Tucker’s showing his face in here just like I told him he would.”

I stood at the counter blushing at Myrna, and waiting for her fuss to die down. What, I’ve known her my whole life and she’s seen me come and seen me go all these years, and the only place I’ve ever seen her was right here.

“Hiya Myrna.”

“That’s what I get from you, a ‘hiya Myrna’? Come here now.” She reached over and pulled me close and gave me a tight hug. “Now what’ll it be, you? You still smoking those fancy ass cigarettes, those ‘organic’ ones? You’re looking sharp there John Tucker.”

“No Myrna, I’m not smoking anymore.”

Myrna beamed, “Well, what could I get ya?”

“How about a couple of those little sandwiches and some home fries too? And a big coffee. I’m making my way down Misery to see my Dad. I’ve been driving all night, I’m starving.” I was wired. And hyper. I couldn’t help playing with the overpriced vanity lighters and novelties and other assorted bric-a-brac on the counter and rummaging around in my pockets for my money.

Myrna yelled back to the kitchen, “Two egg and bacon and a home fries, and the eggs wet.” She looked at me deadpan. “Isn’t that the way you always liked it John Tucker?”

“Yes m’am.”

I handed my money to Myrna and took my big bag of grub. She said, “John Tucker, about your Dad. Tell him I was asking after him would ya? If you don’t mind me speaking outta school,” she got closer and whispered, “They say he hasn’t come out of that house in weeks.”

I smiled and said my thank yous and goodbyes to Myrna. She was still talking after me as the chimes on the front door gave way to the hot morning sun on my face.

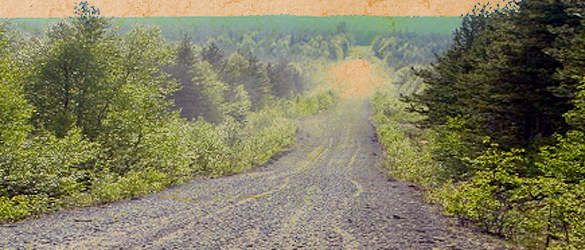

If what Myrna said is true, that’s not a good sign. Dad not coming out of the house I mean. I got in the Dakota and headed west down Misery, putting on my sunglasses to shield myself from the brightening day. I prayed that Dad wasn’t in a bad way again. My plan was to stop in for MAYBE two hours tops, then get out and hit the road back lickety-split! There was so much going on at home with Sarah and the kids, and such tension at work, that I had to get back to California by at least Monday. The last time I talked to Billy on the phone he said Dad was getting worse, and it was becoming way too much for him to handle alone. ‘Something’s gotta give,’ is how he put it. I silently watched the panorama of rolling hills and forest go by as Misery turned to gravel. Although I mostly denied it, I was still so connected to this place.

No matter where you go, there you are.

When I stepped off my truck I could see the property’d gone to shit. Lawn screaming for mowing and house begging for a pressure washer and some fresh paint or something. A spruce-up. Billy said in that going-on way he has that he had someone regular to take care of all the chores—and check in on Dad too—but it was obvious nobody’d done anything in this yard for awhile.

We’ll see what’s happening here.

I picked up the morning paper on the stoop and pulled open the screen door. The TV was LOUD and I found Dad sitting in his recliner with the curtains drawn. Apparently he’d dozed off watching The Millionaire Matchmaker, with that yenta Patty Stanger and her posse of insatiable narcissists doing their thing in his living room. To each his own. I walked into the kitchen and there was a pitcher of Kool-Aid on the counter and half-eaten Stouffer’s lasagna or something of that ilk in an aluminum foil tray with a fork in it. I slid open the windows to let in some air. This kitchen was dingy and messy and needing attention.

I heard the front door creak open, then shut. When I walked back out to the living room, Billy was standing over our now awake Dad, quietly telling him “Johnny’s here, Dad. It’s time for you to get up now to visit. It’s time to get up Dad.”

“No, no that’s okay, Billy,” I said. “Let him rest. I’m gonna straighten up around here and make him a good breakfast for when he wakes up.”

“Well okay, Johnny,” He looked at me thoughtfully. “And while you’re here, the three of us really need to get to talking.”

Okay. Ready to hash things out already. Always the same thing over and over with him. Billy and I hadn’t seen eye-to-eye for years on much. Nothing would surprise me.

I went back into the kitchen and turned on the radio, and ran water in the sink for the piled-up, gunked-up dishes and glasses that were strewn all over. I pulled some butter and eggs and Virginia ham outta the refrigerator and put the coffee on, when Billy came in and immediately started into small talking about my ride down and the weather and other inanities. Then about his annoying wife (from his perspective), and his pain-in-the-ass kid (his perspective again) and our Dad, who he said has been taking up way too much of his time.

Same thing over and over.

I interrupted him. “Billy when is someone gonna get outside and mow that lawn and spruce things up around here? The place looks like shit.”

Billy’s ear cocked and he visibly stiffened. “Well, brother, why don’t you get out there and do it right now?” He was eye-balling me, with his hands on his hips, in that same confrontational way he always had about him. So touchy. Ever since he was a kid.

Eggshells.

“Well you said you had people taking care of all that, and Dad. How is Dad?”

“He keeps asking about you and I tell him you’re coming. Go talk to him a little why don’t you? And think about spending your time here chipping in Johnny. It’s about time you started sharing the load around here.”

I walked into the living room and sat on the love seat next to Dad’s recliner. He was indeed up, well, stirring. His eyes were in the comics of the morning paper. “Dad?”

His head rolled around a bit as he took his eyes off the print. And fixed them on me. “John Tucker?”

“Yeh Dad.” I leaned in and kissed him on the cheek- the way I always did ever since I was a baby.

“John Tucker, they’re treating me terribly around here, when are you coming home? Why don’t you come home and stay with me?”

Billy walked in, interjecting, “Dad, you know Johnny’ll never leave his big city out there. He doesn’t have it in him to come back here and do what’s right.”

“Billy, don’t,” was all I could muster.

“What?”

“You know I try and do what I can. I mean with Sarah and the kids and my job. You know with this economy nowadays, I’m even lucky to have that job. It’s too far to come here more than I already do, Billy, you know that.”

“You don’t know how much I’ve given up here Johnny.”

Dad smiled at me. “John Tucker, is there coffee?”

I went into the kitchen and retrieved some, and put the ham in the broiler to toast. I served Dad his coffee and took my place in the hallway behind Billy who was now talking to Dad about how things were gonna change and what their options were. He was really going at it. I leaned back and held up the wall.

“You know I don’t wanna put you in a nursing home, Dad,” Billy said. “We gotta see now if Johnny can pick it up on his end, okay?” He turned to me. “Johnny, what are you gonna do? You can either come back here to live and take care of Dad, or I’m gonna have to put him in assisted living, there’s no other choice. I can’t do it anymore Johnny, it’s been too many years. And this house. We have to figure things out now. What are you gonna do?”

I was astonished. Billy resented for years that I was the one that got away from Misery Road, and always felt he got the short end of the stick here. But I never would have thought it was to the point where he’d force my hand. We were silent there together for a few very slow and loud seconds.

Dad tried to get up and Billy helped him, till he finally was erect on his feet. Dad looked at me, “Johnny why don’t you come stay with me? Huh, Johnny?”

“I can’t do that, Dad, you know that.”

Billy mimicked, “I CAN’T DO THAT DAD. You’re gonna have to do SOMETHING Johnny.”

“I can’t do that. Billy, you’re gonna have to figure something out.”

Billy’s glazed eyes were fixed on me. “Okay then. Start with the lawn.”

I walked out back to the shed and pulled out the rickety and rusted and totally underutilized lawnmower and started it up. I meandered around the yard cutting the grass feeling queasy and STUCK. Being here always made me feel that way, well at least since Mom died. And it never took long either. But things are different now. Billy’s been stuck here forever right? I’m the one who got away.

It was hot as hell and I was sweating up a storm. It must have been up in the 90s already. The sun was shining on the already big sunflowers, the same sunflowers that me and Billy planted when we were little. Mom egged us on the whole time with that, encouraging us to work together in the garden. Things have changed so much in the years since she’s been gone. I was suddenly overcome with sentimentality. You never know how things are gonna turn out, right? I looked across and down both sides of this modest street at the comings and goings of the neighborhood. The people on this street have known me since the day I was born.

I finished the lawn and walked back in the house.

“Okay Billy, I’ll do it.”

Billy was yammering and laughing with Dad and pointing to the TV, too caught up in some infomercial to notice me. I stepped in front of him. “I’ll do it.”

“Do what, Johnny?” he asked, eyebrows raised.

“Move back here to and stay with Dad.” I looked at my father. “Dad?”

Dad inched over with his arms outstretched. “John Tucker, my favorite. I told you you’d be coming back. You never belonged out in California, come here.” He pointed his elbow Billy’s way. “You gotta give me a rest from HIM, Johnny. He’s trying to do me in. Oh John Tucker, you’re my favorite son. Misery Road. Coming back to Misery Road.”

The smoke alarm went off and the smell of stinking, burning flesh wafted in from the kitchen. I forgot the ham! Billy smirked and turned on his heels. He opened the screen door and left.