The Batman character is what Freud called a truth wrapped in symbolism (Freud, as cited in Campbell, 2008). Never mind that in this particular case, the vast majority of that symbolism involves a man dressing up as a night rodent and performing acts of skydiving, daredevil valor against an assortment of cartoonish and garish nemeses.

Some authors suggest that readers embrace the character because of his inherent humanity (White, Arp, and Irwin, 2008). Batman does not come from another planet, nor is he the result of a radioactive meltdown. He is the product of a tragic event, which is a universal truth to which human beings can relate. We are all very likely to experience tragedy, while the experience of gamma rays is not as wide reaching.

On the other hand, the character spawns from a seemingly endless source of capital. Most of us cannot relate to this. He dedicates his entire life to a cause based on a singular tragedy, which is not often considered healthy or wise. And, as those of us who dressed up as the Batman when we were younger (multiple personal confessions could be inserted here) can tell you, those falls from great heights jar the body, knock out the breath, and take a toll on the muscles that the character does not seem to endure.

Not to mention the fact that the character dresses up as a bat, a central point that barely needs reiteration. Dressing up in like fashion among polite society would surely result in loneliness and obscurity, if not incarceration.

Joseph Campbell’s concept of the monomyth, however, resurrects the character from these vestiges of absurdity. Batman represents a universal overcoming of fear and pain. Christopher Nolan, the director of the much-adored Dark Knight trilogy, cited the character’s movement through fear in his first film, chaos in its sequel, and inevitable pain in the third film (Lucas, 2012). This rise and fall paradigm evokes the pathos of ancient Aristotelian narrative.

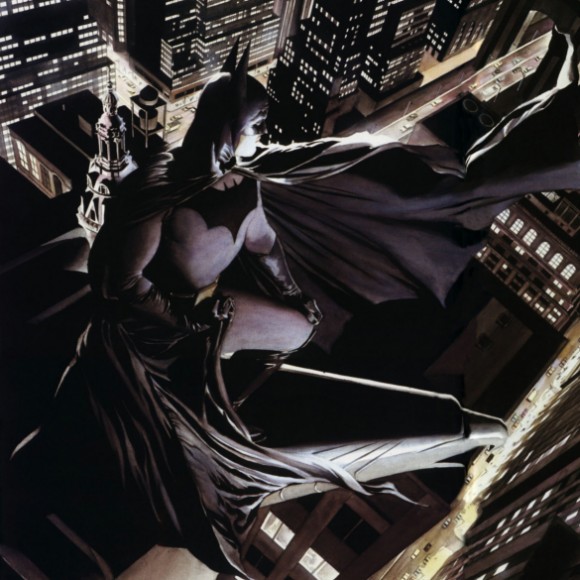

Batman is constantly beginning his adventure again, setting out each new time to recover what he lost, knowing somewhere within himself that the pursuit is futile. The authors and directors who tell his story over and over relish the chase, the images of explosion, and the elaborate plots of the villains, but they also turn the camera away from the character’s interior detonation in these special effects scenes.

The splash page of the comic celebrates the shattering glass without delving too far into the shattered psyche, and the plummet through the plate glass window rather than the descent into a personal abyss. Some of the darker narratives explore these elements with more consideration, but tales of madness tend to focus on the antagonists, rather than on the hero of the journey.

It is possible that readers would not readily embrace a character who represents fear to the degree of mental illness. Bruce Wayne has his quirks, but we like to focus on the fast cars and gadgets more than his psychological exploits.

Still, the rise and fall captures the viewer. We want to see the character ascend from the literal and metaphorical pit. Batman might just as well be dressed as a phoenix, rather than a bat. What makes the existing imagery work more effectively is the “creature of the night” motif, allowing the character to turn personal fears and struggles into a weapon. As a friend of mine recently said, successful people build their homes out of the bricks that others throw at them. Bruce Wayne/Batman has taken the drawbacks in his life and allowed transformation to occur so that he physically and mentally becomes another being.

Most of us do not have an urge to put on a cape and cowl, but there is a ubiquitous need to feel like we are the heroes of our own stories. We can certainly relate to loss. There are times in our lives when we feel we have to find exile, or are forced into exile. Then we hope for a triumphant return.

What makes Batman even more sympathetic, heroic, and tangible is his personal code of conduct, a set of rules that ensures his enemies will always come back without stretches in the narrative. The Batman refuses to kill his enemies. He does not want to sink to the level of the criminal who murdered his parents.

Rather than fully embracing the nemesis aspect of the Oedipus development, the character of Bruce Wayne refuses to supplant his father. His struggle is against himself, and the caricatures of his deepest fears, all of whom meet him with new challenges. Batman has one of the most extensive and remarkable gallery of rogues in all of comic book lore. Perhaps because he is a character of such deep melancholy, he finds himself facing villain after villain, each a representative of his own psychological faculties.

Then again, the argument may arise that the depth of monomyth is misapplied here. After all, we are, discussing a comic book serial and film franchise, obviously intended to rake in cash. Nevertheless, given the level at which some authors have considered the character, it could be said that there is enough evidence after seventy-five years of publication to suggest that there is depth to the story.

Just as mythical and literary heroes commonly experience rises, falls, and find themselves couched in symbolism, so the Bruce Wayne/Batman character may grapple up to the heights of an epic protagonist.

Works Cited

Campbell, J. (2008). The hero with a thousand faces. Novato, CA: New World Library.

Lucas, J. (July 21, 2012). “Why do we fall? The themes of Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy.” http://randomindependent.com/2012/07/21/why-do-we-fall-the-themes-of-christopher-nolans-batman-trilogy/ Retrieved on October 25, 2014.

White, M., Arp, R., and Irwin, W. (2008) Batman and philosophy: The dark knight of the soul. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

JD DeHart is a writer and teacher. His writing has appeared in a number of journal publications, including Eye On Life Magazine, The Commonline Journal, and The Literary Yard.