The Catholic Church seems to be going less traditional these days.

Instead of evoking the usual images of nuns-in-habit, gorgeous gothic buildings with intricate stained glass windows, and elaborate ceremonies filled with the scent of burning incense, the Church seems to want to conjure a different picture for you – and, like most things these days, its digital.

The past few years have seen their fair share of Church vs. Technology battles, ranging from minor comments made by Vatican leadership on the negative impact of technology on daily prayer to more serious allegations that technological advances in science and medicine are at odds with individual human dignity. It seemed inevitable – the Church would assume the same position toward modern technology as it has had toward medieval science. Bring on the inquisition.

But then, on January 24, 2011, Pope Benedict XVI issued an unprecedented new proclamation. In celebration of “World Communications Day,” His Holiness, rather than describing technology as a vice or temptation, argued that “these technologies are truly a gift to humanity and we must endeavor to ensure that the benefits they offer are put at the service of all human individuals and communities.”

While the majority of the speech was dedicated toward not-so-subtle warnings on the easy misuse of modern technologies—its deception, its displacement of truth with subjectivity, its encouragement of virtual versus real friendships, etc. – this one statement seems to have provided the necessary impetus behind changing the relationship status between the Church and Technology from “enemies” to “it’s complicated.”

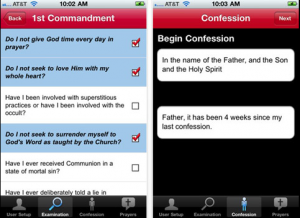

The first major practical Church embracement of His Holiness’s advice arrived a few weeks ago with the development of a new iPhone app, aptly titled “Confession: A Roman Catholic App.” The new program, which was developed by Little iApps of South Bend, Indiana, provides a “personalized examination of conscience for each user,” claims developer Patrick Leinen. Catholics – at least those who can afford an iPhone – can purchase the app for just a $1.99 and get a full walkthrough of the entire sacrament. While absolution can still only be delivered by a priest, the U.S. Conference on Catholic Bishops has already endorsed the technology, hoping it will bring Catholics back into the fold by providing a checklist of age-appropriate sins so individuals can “edit [their] first draft on the iPhone before delivering it orally,” says Father Edward Beck in his “Moment of Faith” vodcast.

As exciting – and unusual – as this technology may seem, its import lies not in its novelty but in the underlying tensions that led to its development in the first place. Why this app, now? The answer seems simple enough – only now do we have the technology to develop such apps. But such a superficial read understands the new relationship as issuing forth from the Pope’s statement in support of technology, rather than the statement in support of technology as issuing forth from some deeper demographical crisis within the Church itself. What is this app meant to solve, and why use technology to solve it? The answer lies in both the history of the Roman Catholic Church and the increasing dissonance between its normative teachings and the reality of Catholic observance in America.

Confession, or the Sacrament of Penance, occupies a central position in the Roman Catholic Church. Composed of three parts, Contrition (the examination of one’s conscious for the commission of sins and the accompanying feelings of remorse), Confession (the oral relation of those sins to a priest), and Satisfaction (the successful completion of the appropriate penalty), Confession joins six other rituals (Baptism, Confirmation, Eucharist, Anointing the Sick, Holy Orders, and Matrimony) as one of the Church’s seven sacraments. While this alone makes it required practice for achieving salvation, Boston College Professor of Catholicism and American Catholic History James O’Toole argues that of all these sacraments, Confession is the single most important practice for all Catholics, even over and above Communion. The theology of Confession has a long and storied past that views the sacrament as an outward sign instituted by Christ to communicate grace to the human soul and can be traced back to the rituals conducted by John the Baptist and those whom he converted at the beginning of Christianity. As with most major rituals, there are two types of support: biblical, and subsequent Church commentary.

Biblically speaking, Confession enters Catholic doctrine in both Matthew and John. To Peter, Christ says: “And I will give to thee the keys of the kingdom of heaven. And whatsoever you bind upon earth, it will be bound also in heaven; and whatsoever you loose on earth, it will be loosed also in heaven” (Matthew 16:19); a similar statement is made to the apostles in Matthew 18:18). Likewise, in John, Jesus’s disciples are told by Christ himself “Receive the Holy Spirit. If you forgive anyone’s sins, their sins are forgiven; if you do not forgive them, they are not forgiven” (John 20:22-23).

Like much biblical evidence, it is difficult to determine prime facie what these enigmatic statements really mean. Here, subsequent Church teachings illuminate the practice of Confession and why it holds such central import in the Roman Catholic Church. Early Church fathers, including St. Ambrose (337-397 CE) and St. Augustine (354-430 CE)argued that these texts implied the power of Apostles – and their modern incarnation, priests – to provide absolution from sins. “It seemed impossible that sins should be forgiven through penance [alone],” St. Ambrose argues. “Christ granted this [power] to the Apostles, and from the Apostles it has been transmitted to the office of the priests” (On Penance II.2.12) Likewise, St. Augustine states “Let us not listen to those who deny that the Church of God has the power to deny all sins” (De agon. Christ, iii). After all, God “promised mercy to all and to His priests He granted the authority to pardon without exception” (St. Ambrose, On Penance I.3.10). The early teachings, then, interpret the biblical texts as asserting two major ideas about Penance: first, that there exists the power to receive forgiveness for one’s sins; and second, that that power is granted exclusively to the successors of the Apostles – that is, the priests. The Canons of Hippolytus and the Apostolic Constitutions confirm these ideas through their record of the prayer used at the consecration of bishops, in which it is to be said, “Grand him, O Lord, the episcopate and the spirit of clemency and the power to forgive sins [emphasis added]” (C. xvii) “according to the power which Thou hast granted to the Apostles” (Apostolic Constitutions, VIII.5).

The High/Late Middle Ages and Renaissance only saw increasing attention paid to the sacrament of Confession within the Roman Catholic Church, likely as a response to Martin Luther’s declaration that any Christian could absolve sins (an idea condemned in 1520 by Pope Leo X). Here, the idea of Confession as not only a necessary means of reconciling oneself to the Catholic Church after sinning post-Baptism but as a practice in-and-of-itself began to assume growing prominence. In 1215, the Lateran Council mandated Confession as a practice to be performed by every Catholic at minimum once a year. Three centuries later, at the Council of Trent, it was determined that:

“As a means of regaining grace and justice, penance was at all times necessary for those who had defiled their souls with any mortal sin…before the coming of Christ, Penance was not a sacrament, nor is it since His coming a sacrament for those who are not baptized. But the Lord then principally instituted the Sacrament of Penance, when, being raised from the dead, he breathed upon his disciples, saying: “Receive yet the Holy Ghost, whose sins you shall forgive, they are forgiven them; and whose sins you shall retain, they are retained” (John 20:22-23) By which action so signal and words so clear the consent of all the Fathers has ever understood that the power of forgiving and retaining sins was communicated to the apostles and to their lawful successors, for the reconciling of the faithful who have fallen after baptism” (Sess. XIV, c.i).

In addition to solidifying the practice of Confession, the Council of Trent also canonically stated that it is only through the intervention of a priest that absolution is achieved. There, the Ecumenical Council determined it as “false and at variance with the truth of the gospel all doctrines which extend the ministry of the keys [that is, the power to absolve sins] to any others than bishops and priests, imaging that the words of the Lord (Matthew 18:18, John 20:23) were…addressed to all the faithful of Christ in such ways that each and every one has the power of remitting sin” (Sess. XIV, C.6). In 1567, Pope Pius V likewise condemned the proposition by Michel Baius (1513-1589), a Belgian theologian, that contrition alone – that is, the sense of complete remorse for the commission of a sin – was sufficient to remit sin without the administration of the sacrament. Not wanting to leave anything to interpretation, the Council of Trent also declared that “For those who after baptism have fallen into sin, the sacrament of Penance is as necessary unto Salvation as is baptism itself for those who have not yet been regenerated [emphasis added]” (Sess. XIV, C.2). Thus, the absolute necessity of Confession, delivered orally to a priest, became canonical in this period and continues to be so today.

While the history of the Church’s insistence on Confession as a central article of faith has only increased over the centuries since the Church fathers, it appears that recent decades have seen a heavy decline in Catholic participation in Confession. James O’Toole’s study of 20th Century American confessional practices, “In the Court of Conscience: American Catholics and Confession, 1900-1975,” argues that after a period of vibrancy, Confession among U.S. Catholics almost completely disappeared in the 1970s. According to O’Toole, in the late 1800s it was entirely common for each individual priest to absolve thousands of parishioners every year and hundreds every day. In fact, it was said that “The spiritual status of a diocese or parish may be safely gauged by the fervor and frequency with which the faithful are accustomed to approach [Confession].” In the early years of the 20th century, the Paulists, who were one of several orders that specialized in domestic mission work, recorded over 120,000 confessions each year in local parishes, with female confession exceeding male confession by almost double. In 1921, in a parish in Marine City containing around 3,000 parishioners, there were over 2,600 confessions every month. Likewise, in 1944 at a parish of 2,500 in Milwaulkee, over 1,300 confessions were heard every month, and even as late as 1952, almost 10,000 confessions were heard every year in a Salt Lake City Cathedral.

The problem, however, hit around 40 years ago. Now, according to Georgetown University statistics from 2008, 62% of Catholics believe – contrary to normative Catholic doctrine – that you can be a good Catholic without participating in the Sacrament of Penance at least one time per year. Over 75% of Catholics report never participating in Confession or doing so less than once per year. Even among those Catholics who attend Mass regularly, only 62% engage in Confession at least once a year. Considering that in 2003 only 25% of Catholics reported regularly attending Mass, the amount of Catholics participating in the Sacrament of Penance is very small indeed. To combat this, Pope John Paul II issued a 2003 proclamation encouraging bishops to prohibit the celebration of General Absolution, a procedure increasingly in popularity in the 1970s in which all eligible Catholics in a given area are absolved for sins without the prior individual confession normally required. Despite this proclamation, it appears that Confession has not increased in any regularity.

There are numerous theories as to why Catholics, despite Catholic teachings, are no longer engaging in Confession. The Catholic Times argues that it is primarily among youth that Confession has ceased to be relevant, and that this can be traced to the Church’s conservative teachings on sexuality as well as the expansion of the concept of sin necessitated by current events. It is true that the pre-Vatican II generation was far more likely to engage in Confession (42% report doing so at least once a year) than the post-Vatican II generation, which only reported 22% participating at least once a year; however, the Millennial generation has increased participation to 27%. It does not appear attributing the decline in participation to merely the youngest generation is an adequate explanation.

That said, Confession is not the only Catholic ritual that is in danger. While the annual rate of infant baptisms per 1,000 Catholics peaked in 1956 at 36.1, in 2009 it had declined to a mere 12.7. While the proportion of Catholics in the United States has remained relatively stable since the 1940s (hovering between 22% and 26%), many of them are choosing to marry outside the Church – and not because of intermarriage. While intermarriage peaked from 1970-1985, the number of Catholic marriages in the US dropped from 15.1 in 1947 to 2.7 in 2009. For some reason, Catholics – even those marrying other Catholics – are doing so outside the church. The problem even extends to convents. The average age for a nun is 71 – no longer are droves of young women donning the habit. As late as the late 1960s, there were 170,000 nuns in the United States; now, there are a mere 66,000. It appears, then, that there is some systemic problem within the Roman Catholic Church and its appeal to American Catholics – and the lack of Confession is merely a symptom of a far more serious virus.

What is the Church doing to address these issues? While it remains to be seen

whether it is merely a superficial glossing-over of deeply rooted problems, Pope Benedict XVI’s endorsement of technology on World Communications Day is a start. After all, our age is the age of information; why shouldn’t that extend to information on Confession, one of the most important and sacred of all Catholic practices? This new iPhone app, for all intents and purposes, provides a digital means of performing contrition – the first step in Confession. Sure, it doesn’t guarantee anyone will see a priest, but it may appeal to those lapsed Catholics who are too embarrassed to go to Church again because they don’t remember the appropriate prayers or technique. So as far as our original question goes – why this app, now? – it appears the answer is obvious: because the Church needs to do something to reinvigorate its parishioners with a love for Catholicism and a desire to embody its tenets – and it’s modernizing old, tried and true techniques to do it. In the Middle Ages, the Church made available small guidebooks – sold for less than a dollar – providing advice on how to prepare for a confession. Today, the Church has endorsed a digital guidebook – available for slightly more than a dollar (gotta love inflation) – providing precisely the same information. So while the Confession App may seem novel, in reality, it’s merely a 21st century incarnation of 16th century practices; and what could be more Catholic than that?