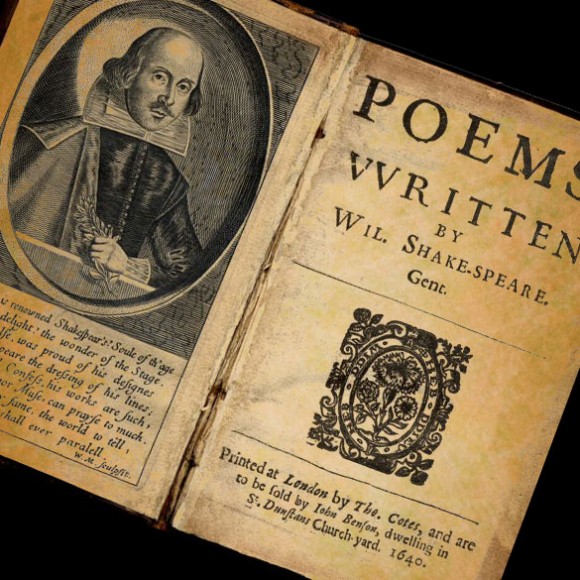

Although skepticism regarding the authorship of Shakespeare’s poetry and plays may well have been expressed as soon as William Shakspere (as the family name is spelled in the Holy Trinity Church Register of Stratford-on-Avon) was publicly acknowledged as the illustrious “Bard of Avon,” the first writer to voice his suspicion was James Wilmot, a retired London cleric who in the early 1780’s settled in Warwickshire and proceeded to gather material for a proposed biography of Shakespeare. When he learned that the most famous inhabitant of those parts may well have been the unschooled son of a local tradesman who left not a shred of evidence that he had ever owned a book or written so much as a letter, Wilmot gave up the project and discarded his notes. He did, however, eventually confide to a member of the Ipswich Philosophic Society that he believed the plays to have been written by someone else who had good reason to conceal his true identity. Wilmot wouldn’t reveal whom he suspected was the mystery playwright, but he hinted that it might be Sir Francis Bacon (Lardner 94).

It wasn’t until 1888, however, that Ignatius Donnely, an erudite threeterm U.S. Representative from Minnesota, “proved” that Bacon was the real Shakespeare. In his book, The Great Cryptogram, Donnely claimed to have discovered hidden ciphers in Shakespeare’s works revealing Bacon’s authorship (Ogburn 13435). For all his brilliance, however, Bacon was no poet and couldn’t possibly have composed the three long rhyming poems, “A Lover’s Complaint,” “Venus and Adonis,” and “The Rape of Lucrece,” or the 154 sonnets and 37 blank verse comedies and tragedies. The Stratfordians (as the traditionalists are called) were quite rightly unconvinced and have subsequently rejected similar claims made on behalf of Christopher Marlowe, Anne Whateley, the 3rd Earl of Rutland, the 6th Earl of Derby and even Elizabeth I (Shakespeare FAQ).

Not only was Shakespeare a supreme poet, a close study of his works demonstrates he was also quite knowledgeable about horsemanship, falconry, botany, biology, landscape gardening, astronomy, law, Italian, French, Latin, Greek, “and a host of other subjects uncharacteristic of the knowledge of a commoner without much formal education” (Lardner 96). In 1908, Sir George Greenwood, an English lawyer, outlined the case against the Stratford man in his book, The Shakespeare Problem Restated, but didn’t claim to know who actually composed the Bard’s great works (Lardner 96). That investigative search was left for another skeptic to conduct.

After years of diligent research during WWI, in 1920 an obscure British schoolmaster named J. Thomas Looney (pronounced Loney) published the most convincing argument yet written on the authorship controversy with his book, Shakespeare Identified, in Edward de Vere, Seventeenth Earl of Oxford. Looney’s method of discovering the Bard’s identity was to examine the works for clues to the author’s probable background, education, personality, point of view and tastes, and then to see if he could match a particular man to the list he had compiled. His study led him to infer that in addition to being a confirmed medievalist both socially and politically, Shakespeare was:

1. A mature man of recognized genius.

2. Apparently eccentric and mysterious.

3. Of intense sensibility a man apart.

4. Unconventional.

5. Not adequately appreciated.

6. Of pronounced and known literary tastes.

7. An enthusiast in the world of drama.

8. A lyric poet of recognized talent.

9. Of superior classical education and the habitual associate of educated people (Looney I: 92).

Focusing on the history plays, particularly those dealing with the turmoil between the reign of Richard II and the ending of the War of the Roses by the downfall of Richard III, Looney detected a sympathy on Shakespeare’s part with the Lancastrian cause and supposed the author to be “a member of some family with distinct Lancastrian leanings” (Looney I: 96). Further examination led him to add nine more traits to his original criteria:

1. A man with Feudal connections.

2. A member of the higher aristocracy.

3. Connected with Lancastrian supporters.

4. An enthusiast for Italy.

5. A follower of sport (including falconry).

6. A lover of music.

7. Loose and improvident in money matters.

8. Doubtful and somewhat conflicting in his attitude to women.

9. Of probable Catholic leanings, but touched with skepticism.

Searching for a possible link between a courtly poet and Shakespeare, Looney discovered a similarity between the ten syllable, six line stanzas of Edward de Vere’s poem “Women” and Shakespeare’s “Venus and Adonis” (1078). Other poems by de Vere only reinforced what Looney suspected, that Shakespeare was the pseudonym of the Earl of Oxford, so he concentrated his efforts on finding further circumstantial evidence that the Bard of Avon was a peer of the realm and not the commoner from Stratford.

Robert R. Prechter, Jr., a Member of The Shakespeare Fellowship and The Shakespeare-Oxford Society, dismisses E.Y. Elliott and Robert J. Valenza’s argument that Edward de Vere’s poetry is nothing like Shakespeare’s. Refuting their computer generated “stylometric matches,” Prechter cites several verse parallels between de Vere’s “The Loss of My Good Name” — composed when he was 16 — and lines from Shakespeare’s plays (The Oxfordian Volume XIV 148-154). In contrast, he finds almost none between Marlowe and Shakespeare (154-155).

Although the Stratfordians maintain that as the son of an alderman, William Shakspeare must have attended the free Stratford Grammar School where he is alleged to have studied Latin, Greek and history, there is no record of his having any sort of formal education; however, even if he had learned to read and write as a prerequisite for admission, the disparity between what young Will might have learned there and the immense frame of reference evident in Shakespeare’s work makes it impossible to believe the two were one and the same man.

Shakespeare was undoubtedly one of the best educated men of his century. He was also one of the more cultured as demonstrated by his knowledge of literature, music and art. In language skills he has no equal. Where the average well-educated person uses about 4,000 words, Shakespeare’s vocabulary is an incredible 17,677, twice the size of Milton’s. The Oxford English Dictionary estimates that he introduced about 3000 mostly Latinate words into English (Ogburn 291).

“Thirty-six of Shakespeare’s plays are set in royal courts and the world of nobility or otherwise in the highest circles of society. From all we can tell, moreover, Shakespeare fully shared the aristocratic outlook of his chief characters. The populace he seems to have regarded as unfit for any share of government…Lower class characters are almost all introduced by Shakespeare for comic effect and are given scant development as such. Their names bespeak their inferior status in his eyes: Snug, Bottom, Stout, Starveling, Dogberry, Simple, Mouldy, Wart, Feeble, Bullcalf, Mistress Quickly and Doll Tearsheet” (240-41).

When he was twenty four, Oxford obtained permission from the Queen to visit the Continent. Most of the fifteen months he traveled abroad were spent in Italy, with the result that six of Shakespeare’s most popular plays take place there: The Comedy of Errors, Two Gentlemen of Verona, The Taming of the Shrew, Much Ado About Nothing, The Merchant of Venice, and Romeo and Juliet.

But why should a noble of the highest rank and sometime favorite of the Queen conceal his identity as the brilliant author of such extraordinary plays with a pseudonym? Two reasons might be given. First, it was not considered proper for a member of the nobility to write for the commercial stage; and, secondly, if the general public knew that the plays were written by a high ranking member of the court they would assume that the fictional characters and events on stage were based on an insider’s accurate knowledge of what was going on within the ruling circle of Elizabeth’s precarious monarchy (Ogburn 189-90).

Read part two here.

—

Fernando Valdivia is an adjunct Associate Professor of English at SUNY Ulster in Stone Ridge, NY. A former free lance drama reviewer for The Times Herald Record in Middletown, NY, his fiction and poetry have appeared in Bluestone Quarterly, Cadence, Esprit, The Glens Falls Review, Oxalis, Riverdreams and The Woodstock Review. A one-act play, Mary O’Connor, was performed at the Harold Clurman Theatre, 412 W. 42nd Street, NYC in 1996 by Love Creek Productions, and a full-length play, The Shunning, was published in 1997 by Eldridge Plays and Musicals. His 15-minute play, Welcome, was performed by Brief Acts Co., at the Creative Place Theatre, 750, 8th Ave., NYC., as well Skirt Job, a one-act comedy in 2004.

One thought on “Will’s True Quill Pt.1”

Comments are closed.