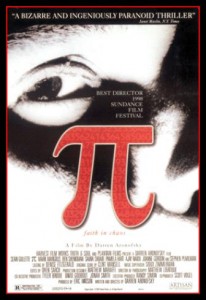

Darren Aronofsky. After his mega-hit “Black Swan,” which has generated 47 wins and 166 nominations on the award show circuit (five are for Academy Awards, including Best Actress, Best Cinematography, Best Director, Best Film Editing, and Best Picture), it seems as if we just can’t get enough of this Harvard-educated film director. Many know him as the Director of former hits The Wrestler and Requiem for a Dream; however, few know of Aronofsky’s debut film, a production funded exclusively off $100 donations from friends and family known as “Pi.”

Pi entered production in February 1996 and premiered at the 1998 Sundance Film Festival, where it won tops honors with the Best Director award. Much like “Black Swan,” “Pi” is a psychological thriller focused on the transformation of a talented, single-minded character’s quest for perfection into a descent into madness. While Aronofsky remained an unknown to most culture mags, Gadfly immediately recognized his talent and was one of the first to sit down with him to pick his brain. In this month’s archived feature, read as former contributor Jayson Whitehead and Darren Aronofsky swap tales on everything from movie-making to religion to life’s major questions.

PI IN THE SKY: AN INTERVIEW WITH DARREN ARONOFSKY

By: Jayson Whitehead, September 1998.

Darren Aronofsky’s directorial debut is a science fiction thriller about mathematician Maximillian Cohen who believes that the universal questions that have plagued humankind for centuries can be solved through a pattern of numbers. As his search progresses, however, he finds that the solution lies somewhere altogether different. Filmed for a mere $60,000, Pi made its world premiere at the 1998 Sundance Film Festival where the 29-year-old Aronofsky received the Directing Award for Dramatic Competition. It also earned him a $1 million deal with Artisan Entertainment and a $600,000 contract to direct the Miramax/Dimension film Proteus about a World War II submarine crew afflicted by Nazis and monsters. For now Aronofsky is allowed a brief respite to bask in his newfound success. Released this past July, the black and white Pi is inventively shot and tightly scripted. A phenomenal first film on the level of Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs or David Lynch’s Eraserhead, there’s many an accomplished director who would like to claim Pi as their own.

JW: I read that Pi was Eraserhead influenced but I didn’t see that in your film.

DA: I think it’s a shallow connection: both films are black and white and about one character. Lynch’s film is very impressionistic and expressionistic, but Pi is really about a story. We were trying to make a thriller the whole time.

JW. His movie is so static whereas your camera is constantly moving.

DA: We tried to keep it moving, keep it exciting. We really wanted a roller coaster ride for 90 minutes. That was the goal.

JW: It reminded me of the Japanese film Tetsuo. Was that an influence?

DA: Definitely—not the film per se—but Shinya Tsukamoto’s entire career. I’m a huge fan of his. About two years ago, I was at Sundance and saw his latest film Tokyo biyori. It totally inspired me to go out to make the cyberpunk movie in America. No one has done the cyberpunk genre over here.

JW: One shot that was really interesting in Pi was when it appeared that some sort of camera was hooked to the main character, Max.

DA: That’s called a “Snorri-Cam.” These Icelandic photographers named the Snorri brothers were using it for still photography and we adapted it for motion pictures. Max is in the center of the frame and the background is moving around him, the idea being that Max is separated from his environment and from his world.

JW: Wasn’t Rod Serling also in the mix somewhere?

DA: Sure. Rod Serling’s totally the patron saint of the movie.

JW: Is that in terms of the story?

DA: Just as a genre in general—the idea of placing science fiction in the present and making it psychological as opposed to effects driven. It preserves the tradition of Serling and Phillip K. Dick in that it works the lines separating paranoia, insanity and genius.

JW: What makes your film sci-fi?

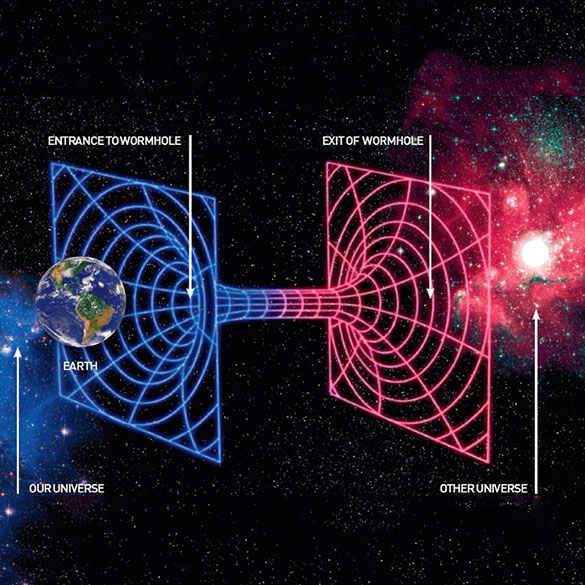

DA: It’s science fiction in the tradition of those two I just named. And it’s science fiction in the sense of the retelling of the mad scientist story. The only difference between my film and Frankenstein is that the monster is named Euclid. It’s just a digital retelling of Frankenstein. In another science fiction sense, it’s a cyberpunk movie. It’s about computers becoming conscious and a mathematician searching for a miracle order in the universe.

JW: In that aspect, it reminded me of 2001: a Space Odyssey.

DA: Kubrick’s science fiction is always about the psychological. There’s serious stuff in that movie. All the effects are inspired by ideas, as is the case with A Clockwork Orange. In fact, A Clockwork Orange had a huge inspiration on Pi in that I was fed up with all the films that had been coming out that weren’t really edgy. In the theaters this past summer, there were no films that had any sort of style or direction—that were cool, hip and different than other films. Growing up, I always wanted to see A Clockwork Orange. I’ve seen it at least ten times in the movie theater because it’s so riveting. I want to aspire to those heights.

JW: Pi’s sound quality was very impressive for such an inexpensive film.

DA: That’s a big failing for independent films and I wouldn’t allow that to happen. With a lot of them you say, “This is pretty good but something’s wrong. It feels cheap.” But nine out of ten times it will be because the sound is bad. We hired a really great sound guy and spent the money on expensive mikes. I also brought in the sound designer and composer very early on so that we could create an entire soundscape. That was very important because we were working with such abstract film stock and shooting a lot of very strange images. It was very important to base the film in a very good sound world.

JW: As far as the theme of the film, were you trying to make a particular anti-technology statement at all?

DA: There’s sort of an anti-science, anti-technology sentiment, but I think there’s more of an anti-religion, pro-spirituality statement. That’s more of what’s going on there. The fear of technology undergirds the film, but it’s not at the forefront. It’s more about a guy who is detached from his humanity, his emotions. He’s become like a machine and is basically a robot running a giant supercomputer in his apartment, who has to reach out and find his humanity.

JW: Do you think religion keeps people from finding their humanity?

DA: No, I think religion is often very different than spirituality. Religion is often about rules and people trying to control our lives who are actually very unspiritual. Another message of the film is that God can be found anywhere, and, in fact, everywhere. And so you don’t necessarily need a religious dogma to get you to spirituality. I would say Max is a very spiritual person, but his spirituality almost killed him.

JW: So all these things—like religion or technology—keep you from reaching your ultimate goal?

DA: Well, they can. They’re basically tools to help us become spiritual. If they’re abused, they won’t help us get there.

JW: The key scene of the film seems to take place when Sol Robeson tells Max the story of how Archimedes discovered the principle of buoyancy. You seem to be saying that it’s important to step back from something in order to reach the desired end.

DA: Sure. There’s a lot in my film. A big part of it is about asking “Why?” and “What is the meaning of life?” The age old questions that people have wondered forever like, “Is there a God?” “Who is God?” “What is God?” Pi suggests some answers but also asks a lot of questions.

“Religion is often about rules and people trying to control our lives who are actually very unspiritual. Another message of the film is that God can be found anywhere, and, in fact, everywhere. And so you don’t necessarily need a religious dogma to get you to spirituality.”

While I do not disagree with this statement entirely, I find it out of character with the director’s other remarks. I hear this sentiment a lot from folks who checked out of religion at a young age often when the precepts of religion failed to mesh with their own daily lives and actions. As a lifelong Catholic now in my mid thirties, I cannot say that I’ve ever encountered anyone in my religious institution trying “to control” me–that’s a gross oversimplification. Nor do I accept this specious division of “religion” and “spirituality,” as if one can’t find within the framework of a millenia-old tradition and set of rituals an avenue for deepening, sharpening and broadening once’s lived experience and encounter with the Divine. By ourselves, do not we tend to be a rather perfunctory, complacent people in our spiritual exercise? The very existence of the billion dollar self-help industry suggests that we’re all looking for a nudge or a push toward our must fully human selves. This is what I encounter in my Catholic faith, and especially in the Jesuit spirituality that begins with the very premise that this filmmaker says religion often misses: a challenge to find God in all things, all peopl–indeed, in all of God’s Creation.