I understand I am late to the game in voicing my opinions about The Cabin in the Woods. The movie has already been picked apart by seemingly all forms of essayistic expression by fanatics and haters alike, or been subjected to the looping rhetoric of reviewers who wish to talk without ever really saying anything. For me, a die-hard horrorphile, someone who truly believes horror cinema is among the most difficult of all artistic expression, this movie required a cool-down period, a releasing of the steam coming out of my ears, before I could allow myself to write one word about it.

Cabin was released April 13, 2012 (a Friday), almost exactly 29 years after the first Evil Dead movie. In Evil Dead, five college-aged friends travel to a mysterious cabin in the middle of unpopulated woods, and unknowingly release an evil entity. The movie changed the genre, and arguably the Hollywood big-budget business model for profitable filmmaking. As 28 Days Later was followed by Shaun of the Dead, as Scream was followed by Scary Movie, so too has the teenagers-in-the-woods plotline reached the point of parody.

I get that horror movies are full of clichés. The characters are beyond tropey—the jock, the whore (as the character Jules is labeled), the intellectual, the burnout, the virgin. The plots are predictable—a warning, an ignoring of the warning, a catalyst to evil, two deaths, an escape attempt thwarted, two more deaths, ending with the last character either surviving or dying. The Evil Dead movies have been successfully indicted, parodied, taken off their pedestal. We see them for what they are. What now?

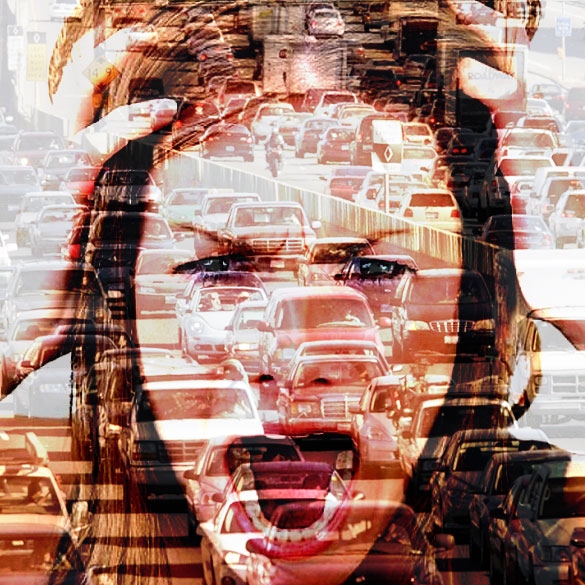

Cabin, put simply, has created a vacuum in the horror genre. The movie sets out to not only show the clichés of horror, but show why we crave these clichés. We, the American paying public, the omnipotent gods of cinema, the capitalist choosers with gigantic right hands symbolically and climactically destroying the cabin, are apparently a testy bunch. The movie tells us that if the whore doesn’t die first, we will revolt; if the jock doesn’t do something brave and ultimately stupid, we will revolt. The movie tells us we don’t care whether the virgin dies or not, so long as she suffers. These conclusions aren’t me being clever—this isn’t analysis—these are expressly stated. Here’s the symbolism: we, the viewers of not only this movie, but all horror movies, are children in need of appeasement, inherently evil and capable of destroying the entire fictional universe in which the movie is set. If the blood of these characters doesn’t fill the archaic ritual room, we walk out of the theater, as Whedon would believe.

A discussion of context is important, here. Cabin is a horror movie for a new generation, some of which hasn’t heard of, much less seen, the Evil Dead movies. I don’t think this is okay—art, movies, can’t be consumed in a bubble, despite what the chapter on New Criticism in your English textbook tells you. Seeing, and talking critically, about Cabin without knowing and understanding the movies it is parodying is like watching the cold open on SNL without being aware that there is a presidential election this year. The lack of context surrounding Cabin has led to some serious misinterpretations—not that I expect accuracy from movie blogs or comments threads. One confused commenter accused Sam Raimi of stealing the plot of Cabin—either this individual is misinformed, doesn’t understand how time works, or is having some type of serious metaphysical meltdown.

Joss Whedon, who co-wrote Cabin and is presumably responsible for much of the film’s ideology, doesn’t hate the genre; he just wants things to change. He shows, in an orgiastic third act revealing every trick up horror’s sleeve, what is scary and why it is scary. He uses the building suspense of music and the sudden absence of sound to forecast a pop-out moment. He uses dark imagery and macguffins. He shows that he can create minor twists that are both surprising and inevitable. He uses the specific sequence of violence, the plot twists, and reliable characters which were used in the first two Evil Dead movies. At best, Cabin is an homage, respectfully toying with narratives which have come before it; at worst, it is an indictment, a summons—you’re wrong for having ever enjoyed the Evil Dead movies.

As David Foster Wallace rebelled against the metafictionists with Westward the Course of Empire Takes its Way, Whedon is too left in a vacuum of his own deconstruction. He shows the pitfalls of modern horror, but offers no alternative. The comparison to Wallace’s Westward is highly generous in terms of ambition and tact, but is also potentially interesting. We’ve seen what horror shouldn’t be—now, we need to see what it should be, what it can be.

Therefore, the success or non-success of Cabin is perhaps yet indeterminable. The movie has ended without possibility of a sequel—not that we would need, or would want to sit through, another 90 minutes of meta-horror cliché indictments. This movie has shown how and where other movies before it have failed—how, then, should horror be done? I await Whedon’s next horror film, and will judge its success or failure like I would a textbook.

With every trope of the genre revealed, every trick now expunged, with what do you now scare us? The movie begins with a droll, office-set discussion of fertility by the two ‘makers’ of the horror-filled environment, suggesting a new kind of movie will be birthed. We fans of horror are at a very curious turning point in the genre. What’s next?

I think you should read the review of “cabin..” by vigilantcitizen.com as it seems to me you have completely misunderstood its meaning…….

Regards, tom

Hi Tom, thanks for pointing this out.

As I mention in my essay, I think there is a lot of misinterpretation floating around on the internet about this movie. The great thing about Cabin is that it leads to multiple interpretations.

I believe the Vigilante Citizen essay takes the movie too literally, and it is not a movie that rationally allows literal interpretation. I respectfully can’t buy into this idea of the literalization and fictionalization of occult rituals. To interpret this movie literally, you would have to believe that some grand organization is capable of producing dumbening hair-dye, mind-control smoke, giant force fields, and a cubic grid containing nightmares. Come on, now.

I think this interpretation is possible, but for me, just isn’t interesting.

For me, a meta interpretation is the only way to watch this movie. It’s a very clever movie, and makes some good commentary on the horror genre and slasher films.

I wonder what you think?

In other words, if the thesis statement of this movie, as Vigilant Citizen would believe, is that there are secret societies controlling the population and executing literal blood rituals to sate the devil, then what credibility does the movie maintain by the time we reach the last scene? The movie becomes a 90-minute eye roll. Taken literally, this movie loses all ethos, and more importantly, all relevance.