“I’m disgusted by what we’ve become in America. I truly believe there is brain death in this country. Everything we see is designed to sell us something. The only thing they want to do is take our money.”—John Carpenter

John Carpenter’s films, known primarily for their horror themes, inevitably feature pulse-pounding soundtracks, slow-moving camera work and hair-raising jolts to the nervous system as evil pops into the foreground with unexpected intensity. However, while Carpenter’s films are also infused with a strong anti-authoritarian, laconic bent, those seeking a good scare tend to overlook the deeper, overarching themes that speak to the filmmaker’s concerns about the unraveling of our society, particularly our government.

Carpenter, as author John Muir writes in his insightful book The Films of John Carpenter, sees the government working against its own citizens. This theme features prominently in the films I explore in my new book, A Government of Wolves: The Emerging American Police State, which examines how writers and filmmakers have used science fiction to forecast the future, hold up a mirror to the present, and most important of all, engage their audiences in a critical dialogue about what happens when power, technology and militaristic governance converge. Yet even among a pantheon of dystopian films such as Minority Report, Nineteen Eighty-Four, The Matrix, and V for Vendetta, Carpenter’s work stands out for its clarity of vision.

Carpenter is a skeptic and critic. But “a close view of Carpenter’s work reveals a romantic streak beneath the skepticism,” writes Muir, “a belief down deep—far below the anti-establishment hatred—that a single committed and idealistic person can make a difference, even if society does not recognize that person as valuable or good.”

In fact, Carpenter’s central characters are always out of step with their times. Underneath their machismo, they still believe in the ideals of liberty and equal opportunity. Their beliefs place them in constant opposition with the law and the establishment, but they are nonetheless freedom fighters. When, for example, John Nada destroys the alien hyno-transmitter in They Live, he restores hope by delivering America a wake-up call for freedom.

This is the theme that runs throughout Carpenter’s films—the belief in American ideals and in people. “He believes that man can do better,” writes Muir, “and his heroes consistently prove that worthy goals (such as saving the Earth from malevolent shape-shifters) can be accomplished, but only through individuality.”

Thus, John Carpenter is more than a filmmaker. He is a cultural analyst. The following are my favorite Carpenter films.

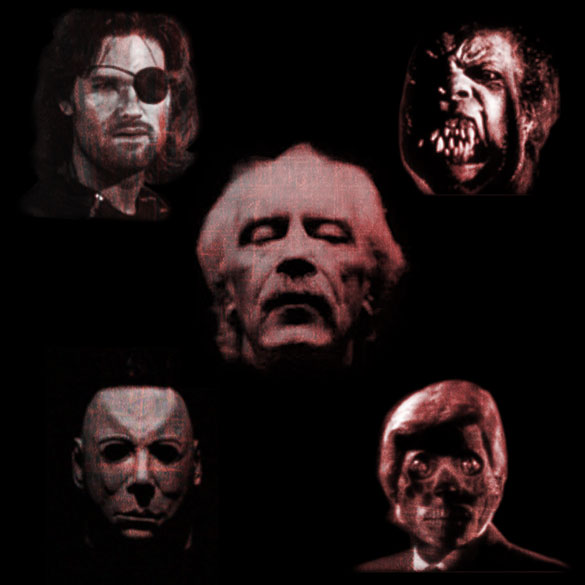

Assault on Precinct 13 (1976): This is a remake of Howard Hawks’ 1959 classic western Rio Bravo—much beloved by Carpenter. A street gang and assorted criminals surround and assault a police station. Paranoia abounds as the police are attacked from all sides and can see no way out. Indeed, Carpenter repeatedly has his characters comment, in disbelief, that “This can’t happen, not today!” or “We’re in the middle of a city … in a police station … someone will drive by eventually!” Or will they?

Halloween (1978): This low-budget horror masterpiece launched Carpenter’s career. Acclaimed as the most successful independent motion picture of all time, the story centers on a deranged youth who returns to his hometown to conduct a murderous rampage after fifteen years in an asylum. This film, which assumes that there is a form of evil so dark that it can’t be killed, deconstructs our technological existence while reminding us that in the end, we all may have to experience Orwell’s stamping boot on our faces forever.

The Fog (1980): This is a disturbing ghost story made in the mode of Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963). Here the menace besieging a small town is not a pack of winged pests but rather a deadly fog bank that cloaks vengeful, faceless, evil spirits from which there may be no escape.

Escape from New York (1981): This is the ultimate urban nightmare. A ruined Manhattan of the future is an anarchic prison for America’s worst criminals. When the U.S. president is captured as a hostage, the government sends a disgraced, rebellious war hero into Manhattan in what seems to be an impossible rescue mission. In fact, this film sees fascism as the future of America.

The Thing (1982): Considered by many as one of Carpenter’s best films, this is a remake of the 1951 sci-fi classic of the same name. A team of scientists in a remote Antarctic outpost discover a buried spaceship with a ravenous, mutating alien that eventually creates a claustrophobic, paranoid environment within their compound. The social commentary is obvious as the horrible creature literally erupts and bursts out of human flesh. This film presupposes that increasingly we are all becoming dehumanized. Thus, in the end, we are all potential aliens.

Christine (1983): This film adaptation of Stephen King’s novel finds a young man with a classic automobile that is demonically possessed. The car, representing technology with a will and consciousness of its own, goes on a murderous rampage. Do we now face the same possibility with the emergence of artificial intelligence?

Starman (1984): An alien from an advanced civilization takes on the guise of a young widow’s recently deceased husband. The couple then takes off on a long drive to rendezvous with the alien spacecraft so he can return home. Surprisingly, as John Muir recognizes, this film is a Christ allegory with the alien visitor possessing extraordinary powers to heal the sick, resurrect the dead, and perform miracles. The question posed is whether the only hope for humanity is a visitor from another world.

They Live (1988): This film, which I explore in greater detail in A Government of Wolves, assumes the future has already arrived. John Nada is a homeless person who stumbles across a resistance movement and finds a pair of sunglasses that enables him to see the real world around him. What he discovers is a monochrome reality in a world controlled by ominous beings who bombard the citizens with subliminal messages such as “obey” and “conform.” Carpenter makes an effective political point about the underclass (everyone except those in power, that is): we, the prisoners of our devices, are too busy sucking up the entertainment trivia beamed into our brains and attacking each other to start an effective resistance movement.

In the Mouth of Madness (1995): A successful horror novelist’s fans become so engrossed in his stories that they slip into dementia and carry out the grisly acts depicted in his books. When this film was being conceived, politicians were criticizing horror movies for promoting violence. Carpenter parodied this argument while noting that evil grows when people lose “the ability to know the difference between reality and fantasy.” As we lose ourselves in ever-evolving technology, we are increasingly blurring that distinction. Does that mean evil will eventually overcome us all?

As freedom crumbles around us, why do “we the people” allow it to happen? As the Bearded Man in They Live tells us:

The poor and the underclass are growing. Racial justice and human rights are non-existent. They have created a repressive society and we are their unwitting accomplices . . . They are dismantling the sleeping middle class. More and more people are becoming poor. We are their cattle. We are being bred for slavery.

Thus, in Carpenter’s view, the real enemies of freedom—the real aliens—are us. As one of Carpenter’s characters concludes in They Live: “Maybe they’ve always been with us…those things out there. Maybe they love seeing us hate each other; watching us kill each other off; feeding on our own cold…hearts.”

The lesson: they live, because we sleep. Time to wake up.

WC: 1279