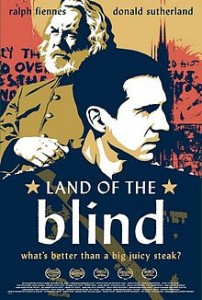

“You know what they say, under the old government man exploited man, but since the Revolution it’s the other way around”

-Joe, prison guard and doomed protagonist in the “Land of the Blind” (2006)

It’s a familiar notion. The despotic cycle. A world in which oppression never sets, and an uncanny autocrat rises predictably again. In the “Land of the Blind,” oppression is neither created nor destroyed: it is simply transmuted into another state of existence.

“Land of the Blind” places a satirical lens on the notion of the cyclical dictatorship. The movie hones in on a place called Everycountry and the experiences of Joe (Ralph Fiennes), a prison guard working under the regime of Maximilian II (Tom Hollander), an autocrat who echoes Napoleon in both stature and ego. In carrying out his duties, Joe encounters a political prisoner named Thorne, a playwright and leader of the revolutionary group, the Citizen for Justice and Democracy. The guard and revolutionary form a friendly relationship, discussing the poetry of Yeats and questioning the legitimacy of Maximilian, or “Junior’s” authority. Joe ultimately helps Thorne in a plot to assassinate Maximilian and his wife, Josephine (Lara Flynn Boyle) yet inadvertently helps to erect a similarly oppressive government. “Chairman Thorne” comes to power, burning books, forcing women to wear burqas, closing universities, and sending insurgent voices to “re-education camps” where people are taught that red means green and stale bread is “better than a big juicy steak.” The cycle of despotism begins again.

and the experiences of Joe (Ralph Fiennes), a prison guard working under the regime of Maximilian II (Tom Hollander), an autocrat who echoes Napoleon in both stature and ego. In carrying out his duties, Joe encounters a political prisoner named Thorne, a playwright and leader of the revolutionary group, the Citizen for Justice and Democracy. The guard and revolutionary form a friendly relationship, discussing the poetry of Yeats and questioning the legitimacy of Maximilian, or “Junior’s” authority. Joe ultimately helps Thorne in a plot to assassinate Maximilian and his wife, Josephine (Lara Flynn Boyle) yet inadvertently helps to erect a similarly oppressive government. “Chairman Thorne” comes to power, burning books, forcing women to wear burqas, closing universities, and sending insurgent voices to “re-education camps” where people are taught that red means green and stale bread is “better than a big juicy steak.” The cycle of despotism begins again.

The film’s political allusions are vast, reaching to imagery associated with Mao Zedong and the People’s Republic of China, Communist Russia, Jean-Paul Marat and the French Revolution, the Taliban, and Nazi Germany, to name a few. Director Robert Edwards’ satire also takes aim on cultural topoi, critiquing the media, western consumerism, and even 19th century minstrelsy. The only subject that remains free from criticism is literature. Joe and Thorne share an appreciation for Yeat’s prophetic work, “The Second Coming,” its familiar lines echoing throughout the film. The gyre widens as we wait for a revelation, a new democratic leader to take the place of Maximilian’s violent regime. Yet in this dystopian universe ruled by megalomaniacal men, words are ultimately manipulated, forgotten, or destroyed, and it appears less and less likely that a revelation will come.

“In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king,” wrote Erasmus in his Adagia, metaphorizing the degenerate state of humanity and its corrupt leaders. Following from its adapted title, the “Land of the Blind” denigrates the concept of the honest politician that can selflessly rule a state, arguing ultimately that this character doesn’t exist. Indeed, the movie begins with its hero, Joe, wasting away in prison, leaving little hope for his or society’s redemption. By the end of the movie, the question remains, is there anyone good enough to break free from the interminable fetters of political self-interest to rule? In the land of the blind, can that man exist?

The topic is undoubtedly an important one. Yet in attempting to grapple with these big questions, Edwards tries to accomplish too much, resorting to clichés of dictatorship that come off as stale. The Orwellian concept of doublethink is recycled in obvious ways, with Orwell’s “2+2=5” translated into “stale bread is better than a big juicy steak.” Too easily, we make the connection from “Chairman Thorne” to “Chairman Mao.” The “Land of the Blind” is ambitious in its criticisms of authoritarianism and, at times, succeeds in bringing fresh ideas to the oft-portrayed subject. Yet despite the successes of the film, it does not amount to a novel rendition. If Edwards wants to re-visit this subject, he must not rely so much on trite motifs.

Despite its flaws, “Land of the Blind” can help to provide some insight into the current political situation in Egypt. According to a recent Atlantic article, “masked military police officers” attacked protesters last Friday and have taken control of Mubarak’s state-run media,![]() putting into question the likelihood of democracy taking hold in the autocratically-inclined country. Protesters continue to take to

putting into question the likelihood of democracy taking hold in the autocratically-inclined country. Protesters continue to take to

the streets, arguing that their demands have not been met, e.g., their desire for the security police to be disbanded. A complete revolution has not yet taken place, making it too early at this point to assert a parallel between the cyclical authoritarianism in “Land of the Blind” and the military’s taking control of the Egyptian government. Yet in a country where the military has propped up powerful dictators since 1952 and demonstrated behavior desirous of quelling protestors’ voices, a film such as this, despite its flaws, can help us to recognize and to, the best of our abilities, understand the ease with which a state can fall back into its regular oppressive patterns. As stated by Dr. Joshua Stacher, an expert on the topic of authoritarian governments, “We’re working with an actor that has an established behavior pattern. Since 1952, the military has not been a force for democracy.” With the military establishing a timetable for democracy earlier this week, we can only hope that, in Egypt, man stops exploiting man this time.