Woke up this morning and it seemed to me,

That every night turns out to be a little bit more like Bukowski.

And yeah, I know he’s a pretty good read.

But God who’d wanna be?

God who’d wanna be such an asshole?

God who’d wanna be?

God who’d wanna be such an asshole?

–“Bukowski” by Modest Mouse

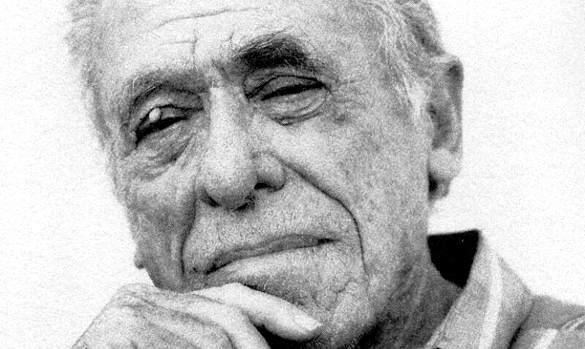

Being an “asshole” worked for Bukowski. Doing so made him the “Poet Laureate of Skid Row,” the acclaimed “laureate of American low-life.” Being an asshole made him famous, and more interestingly, it garnered him heaps of admiration. Even after his death in 1994, poet, short story writer, novelist, and cultural outsider, Bukowski continues to fulfill the role of the much-beloved anti-hero, to epitomize it, a beacon of bone-bare honesty that repels some readers and simultaneously draws a loyal coterie of admirers.

Born in Andernach, Germany in 1920, Henry Charles Bukowski and his family immigrated to the United States when he was two years old, settling permanently in Los Angeles. Bukowski described his childhood, a period in his life depicted in Ham on Rye, his semi-autobiographical novel, as a time of “utter grimness,” a “horror story with a capital ‘H.’” His abusive father beat him frequently with a razor strap for absurd peccadillos such as failing to trim every hair on the family’s lawn, and his mother, a “typical German woman” was passive and obedient, an espouser of the motto, “your father is always right.”

During his younger years, Bukowski also suffered from acne vulgaris, an agonizing condition that implanted boils on his face, neck, back and chest and induced ridicule from his classmates. In an event that he would later recall as “magic,” his friend invited thirteen-year-old Bukowski over to his father’s wine cellar where he had his first encounter with alcohol. He studied journalism, literature, and art at Los Angeles City College before dropping out and moving to New York, marking the beginning of a period that Bukowski deemed, his “ten year drunk” in which he quit writing, worked a plethora of small jobs, and travelled across the country, a period that inspired a great deal of his writings. In 1952, Bukowski resettled in L.A. and worked for the U.S. Postal Service, an occupational position famously depicted in his novel, Post Office. After nearly dying from a bleeding ulcer in 1955, Bukowski returned to the typewriter.

Bukowski began his career publishing in small presses and in local papers such as Open City, gaining attention via word-of-mouth. He published his first story, “Aftermath of a Lengthy Rejection Slip” at the age of twenty-four and began writing poetry at thirty-five. While Bukowski stated that he realized he was a writer at a very young age, he only became a full time writer at thirty-five, when John Martin from Black Sparrow Press offered to give him $100 a month for the rest of his life for Bukowski to quit his job and write full-time, for a living. Even after he gained fame, he remained loyal to the tiny magazines that published him in his early career.

While some would like to write Bukowski off as a base misogynist, his work is significantly more nuanced than his critics assert. Bukowski’s literary alter ego, Henry Chinaski, never commits the most horrific acts of violence, rape, and murder against women. Bukowski reserves these crimes for lower-lives, the truly banal.

“While reading your book Women, one could get the impression that for you a woman is nothing more than a behind and a pair of tits,” a Belgian reporter once told Bukowski in an interview. Watching the video of the two men sitting together on a couch in Bukowski’s home, facing each other in uncomfortable proximity, Bukowski looks discernibly puzzled by the reporter’s assumption, a blank expression marking his face, bewilderment wiping away all other emotion.

“Oh, c’mon, you read it and that’s all you got?…I mean no, there are many moments in there where I look like a complete asshole, and I felt like one. No no. I just wasn’t jumping into bed and fucking and jumping out of bed. I’m sorry. It would be nice for me to say that and pretend that I’m a tough guy, but I’m not that tough.” The reporter continues to enlighten Bukowski with his own interpretations: “But in your stories, love is always a synonym for sexual intercourse.”

“Where do you get this crap, baby? Love is a dog from hell. That’s all. It has its own agonies. It brings its own agonies with it. But I don’t know where you get your concepts from man. You really fucked up.”

Bukowski’s poetry is perhaps most demonstrative of his emotional and intellectual complexity, which when philosophizing on concepts such as loneliness, love, and the mire of everyday life in conjunction with boozing, violent, and graphic depictions of the low-life lifestyle, form a disconcertingly realistic, contradictory corpus of literature. One poem, “The Genius of the Crowd” is an angry, a fearful thing that depicts his distrust of people. He writes,

beware the average man the average woman

beware their love, their love is average

seeks average

but there is genius in their hatred

there is enough genius in their hatred to kill you

to kill anybody

His fears of relationships and people arise throughout his work. In “Alone with Everybody,” he writes,

the flesh covers the bone

and they put a mind

in there and

sometimes a soul,

and the women break

vases against the walls

and the men drink too

much

and nobody finds the

one

but keep

looking

crawling in and out

of beds.

flesh covers

the bone and the

flesh searches

for more than

flesh.

there’s no chance

at all:

we are all trapped

by a singular

fate.

nobody ever finds

the one.

As Bukowski says of himself, as much as critics would like to believe that he is the “tough guy,” he is a multifaceted character incapable of being labeled with a tidy brand. He is raging, melancholy, sexual, frightened, confident, bestial. He is a jagged peg that refuses to slide into a neat hole. There is no one quite like him in recent literary history.

While David Foster Wallace probably comes the closest to achieving the cult-level worship achieved by Bukowski, his page-length-sentenced, footnote-toting style is significantly less accessible, more difficult to embrace for most. Access and appreciation of DFW’s rich work is restricted to the truly stalwart reader. Unlike the scholastic cult-hero DFW, Bukowski was the “writer for the dispossessed,” for “people who didn’t have a voice.” In the words of his publisher, John Martin, Bukowski was the “equivalent in today’s world of Walt Whitman.” He was the everyman’s hero because he was a regular “asshole,” a man and not an inviolable god. Hero is most definitely the wrong word. He was just an artist.

Listen to Buk reading “Dinosauria, We”