Victor Bockris: On the other hand, you always said you just like to have people who talk a lot when you turn the tape recorder on.

Andy Warhol: Well, listen, that’s the thing. I mean, God! That’s your interview. I didn’t get one word in, so that was the ultimate. It was the perfect interview. The nice thing is that he lets everybody come up, which is kind of great.

—In a limousine, leaving Muhammad Ali’s training camp, Deerlake, Pennsylvania, August 15, 1977

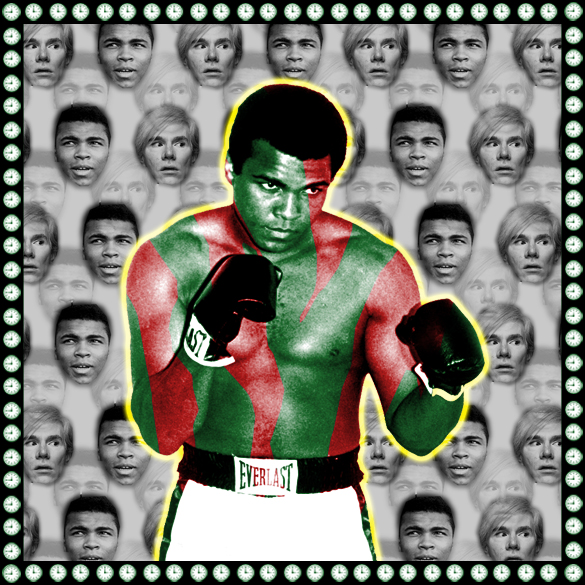

Back in that peak year of the punk ’70s, 1977, I introduced two punk godfathers, Andy Warhol and Muhammad Ali. The world heavyweight champion of art had been commissioned to paint a portrait of the World Heavyweight Champion of boxing. In 1974, I wrote a short book about life at Ali’s training camp, Fighter’s Heaven. In 1977, I had just started working for Warhol at his Factory. In fact, traveling with Andy from New York to Deerlake, Pennsylvania, to act as a buffer between him and Ali was my first assignment.

At the time, Ali and Warhol had so much in common that I had written in an article that was published one month earlier, “Who Does Andy Warhol Remind You of Most? Muhammad Ali,” They both came to prominence in 1964. Ali, who had beat Sonny Liston for the heavyweight title, showed a propensity for putting his mouth and face to good use for publicity. Warhol, who beat Jackson Pollock for the unacknowledged heavyweight title of the most famous painter, also showed the same propensity.

Each man came from poverty (although Warhol had been ten times poorer than Ali) and eventually transformed his profession into a multimillion-dollar-a-year industry. Each became an icon. After catastrophic setbacks (Ali barred from boxing in 1967, Warhol shot in 1968), however, both made remarkable comebacks in the 1970s, becoming international superstars and multimillionaires. Motivated by money, these two men made it their language, but they did it with a humorous, philosophic twist.

By 1977, Ali and Warhol faced career crises. Though holding their own, they were shadows of what they had been in their prime. Warhol had one vital attribute Ali was missing: He drew a sharp head on other people that he put to good use. Ali was so fixated on his own greatness that he often exercised poor judgment about other people. When the two men met in 1977, Warhol had regained much of the strength he lost after the 1968 attempt on his life, and he made the remainder of the 1970s a productive and successful time. Ali, on the other hand, was skidding downhill dangerously fast. Warhol was a smart businessman who maintained control over every aspect of his work. Ali had less control of his life and career. Capable of generating an enormous amount of money in a short time, mostly in cash, he attracted all the creeps, parasites and criminals in the country who could worm their way into his entourage.

It was not until I sat down to write this piece, re-listening to the tapes I recorded that day in light of the information we have since received about the brain damage Ali suffered in the latter half of the ’70s, that I began to see and understand what really happened in the meeting between these two men.

On the surface, the sole purpose of their meeting was to make money. A New York businessman, Richard Weissman, had contracted Warhol to do a series of portraits, “The Ten Greatest Athletes.” The product would consist of six copies of each forty-by-forty-inch silk-screened portrait (acrylic on canvas) and five hundred prints of each image. In exchange, Warhol was to be paid one million dollars. Each athlete was paid fifteen thousand dollars to let Andy take as many Polaroids of them as he needed to find the right image to be silk-screened onto canvas as the basis of their portrait. They would also receive one of the six commissioned paintings, valued at twenty-five thousand dollars each.

On the ten to fifteen occasions I visited Fighter’s Heaven between 1972 and 1974, I saw the many moods of Muhammad Ali. At times he was the most infectiously happy person I had ever met. Being with him was sheer joy, whether we were barreling down the highway in his touring bus with Ali at the wheel, watching a video of one of his fights as he flicked punches past my ear, or tape-recording one of his supersonic raps. On other occasions, he could be withdrawn and appear badly troubled. Once, I saw him call for a handgun and fire a salvo of shots into the woods below the camp in what appeared to be a pent-up Elvis-like rage. But whatever his mood, once I got him talking about or reciting his poetry, Ali’s troubles seemed to blow away. He had some quiet, serene scene at the center of his being that kept him balanced throughout the constant tumult of his existence then. I was not prepared, however, for the way he treated Andy Warhol.

We arrived at the camp for our appointment at exactly 10 am, Thursday, August 15, 1977. Ali had flown in from Europe the night before and was a little behind schedule, an aide explained. At 10:45, clad from the head to foot in black, Ali stepped out of the log cabin he slept in while he was training and joined us in the camp’s courtyard, delineated by the kitchen, the gym and a beautiful panoramic view of the Pennsylvania countryside. The aide introduced Ali to Warhol, but Ali appeared to be elsewhere. Studiously staring at the bright blue, empty sky, he barely proffered a curled paw for Warhol to shake. The atmosphere was tense. As the party moved toward the gym where the photo session was set up, I welded myself to Ali’s side, aiming to be a go-between as the need arose. Ali was clearly sluggish. He had just completed a two-week publicity tour of thirteen European cities and was scheduled to start training for what would be a hard fight against Earnie Shavers immediately after our visit.

As we walked, he started unraveling a surreal account of his recent travels: He told me that he’d just been in Gottenberg, Sweden, talking to twenty-three thousand people, “They paid me twenty thousand dollars for four hours.” The mounted police had to rescue him from the crowds in Sweden by putting him on a horse. The people of South Africa had sent a representative to thirteen cities across Europe looking for him to beg him to be their leader; all the archbishops in England wanted him to preach in their churches; twenty thousand people mobbed him at the houses of Parliament; and the London blacks begged him to lead them in their summer riots: “Fifteen minutes after I told them ‘No,’ in my suite at the Hilton,” he laughed, “they were over in Notting Hill fighting the police. I can’t be responsible for starting no trouble in somebody else’s country…”

We passed through Ali’s dressing room, where his trunks, jock strap, shoes, socks and boxing gloves were laid out for the afternoon’s sparring session, and entered the gym. Ali slumped onto a folding metal chair that had been set up in front of a white backdrop for the photo session. Normally, it is at this stage that the subject and artist begin to relate. But Ali continued to behave as if Andy Warhol were not there.

I crouched down on the floor, five feet away, so as to stay out of the camera’s range but be close enough to continue a conversation. Now Ali started going into overdrive, talking about how he’d only realized on this trip how famous he really was and how many people wanted to see him. Meanwhile, Warhol was snapping a lot of useless profiles of Ali talking, but however hard I tried, I could not stop Ali’s monologue or redirect his attention away from me and toward Warhol. Then, suddenly, Ali gave us an opening. “How much are these paintings gonna sell for?” he asked.

“Twenty-five thousand dollars,” answered Warhol’s business manager, the snappily dressed, sleek Fred Hughes. “Can you turn yourself a little bit towards the camera, champ?”

The answer arrested Ali’s flow of thought. “Who in the world could they get to pay twenty-five thousand dollars for a picture?” he asked incredulously, almost levitating from his seat.

“He’s sold quite a few for more than that!” Hughes replied, whispering, “We should have brought down one of Andy’s black drag queens. They went for twenty-eight thousand dollars each.” But Ali was buried in the equation. Launching into a rap about God, he concluded that, “Man is more attractive than anything else!” and then turned our attention fully onto him. “Look at me! White people gonna pay twenty-five thousand dollars for my picture! This little Negro from Kentucky couldn’t buy a fifteen hundred-dollar motorcycle a few years ago and now they pay twenty-five thousand dollars for my picture!”

Although Ali was not willing to share any of the credit for this remarkable state of affairs with the artist, the exchange broke the ice, and soon Warhol uttered his line of the day: “Could we, uh, do some, uh, pictures where you’re not, uh, talking?” he asked, in the brittle, querulous voice he reserved for just such occasions. For a split second, there was a white light of silence in the room. Nobody had ever told the champ to shut his famous mouth in quite such a not-to-be-trifled-with way. Even I was not sure what this turn of events might portend. But then Ali broke into the silence, chuckling quietly to himself, “I’m sorry, I should be doing your job. You paying me.” Instantly becoming the professional, he flipped through a series of classic poses.

Andy leapt into the moment, egging him on, “Just like that…That’s really good…Just a couple more.”

“I wish you could take pictures in five weeks when I get more trim. A little more prettier,” Ali griped, pinching a tire of flesh around his belly.

“Just three more,” Andy urged. “Could you put both fists close to your face?”

“How about this!” Ali exclaimed, bringing his fists up into the classic boxing position, just in front of and below his chin.

“That’s great!” Andy chimed. “Closer to your face…more…”

“Do I look fearless?” Ali growled.

“Very fearless,” Andy replied. “That’s fantastic!”

Warhol’s strongest suit as a portrait painter was making people feel and look fabulous by focusing all his powerfully seductive attention on them. In those three minutes, Andy had restored Ali to the generous, fun-living host that I had met in 1972. Waving aside aides who were about to escort us out, now that our job was done, Ali announced that he wanted to show Andy around his camp, introduce him to his wife, take a look at the brand new mosque he had just built.

I was delighted by the turn of events and began looking for an opportunity to record some quotable conversation between the two icons. As the rapid tour neared its end, Ali signaled another stop, inviting us to join him in his log cabin to listen to him read a poem he’d written the night before on the Concorde. I found myself striding between them on a narrow path that ran alongside the gym. Ali had jut starred in the biopic The Greatest, which had been a resounding flop. Warhol was about to release what would turn out to be his last film, Bad. Perhaps this was grounds for a conversation. “Well, you know,” I began, “Ali’s interested in getting into films, Andy, and you make films, so maybe…” but before I could finish the sentence, a horrified Warhol peeled away mumbling something about “checking on the photographs.” Without breaking stride, Ali launched into a tirade on blaxploitation films: “Blacula! Cotton Comes to Harlem! Nigger Charlie! He snorted. “I predict they ain’t never going to make a real black movie.” Despite my faux pas, and the uneasy revelation that tension still lurked beneath the surface, I followed Ali into the cabin, where we were joined minutes later by Warhol and Hughes.

Inside, the single room was virtually empty. A large gold-framed four-posted bed, which Ali told us cost eleven thousand dollars, stood in one corner. Ali sat in the opposite corner in an armchair. Warhol perched on a small hardback wooden chair facing Ali across a low-slung coffee table. I crouched on the floor to Warhol’s right, looking up at Ali. Hughes hung onto one corner of the bed. None of us had slept much the previous night.

As Ali read his poem about the Concorde, I marveled that we were recreating the very setting that had proved so productive for me, interviewing Ali over the years. Once you had shown interest in his poems, he was much easier to interview. I switched on my tape recorder.

As soon as Ali finished the poem and we had murmured our appreciation, a brief silence fell upon the room. In retrospect, if I had leapt in and started interviewing Ali, I might have been able to avert the onslaught that was to come. However, I made the mistake of thinking that Andy, in the catbird seat, would pick up the slack. But then Andy was the master of not picking up the slack. I noticed with mounting concern that Ali’s big hand was fishing into one of three wide open briefcases at his side while his eyes trained relentlessly on Andy’s face. Then his hand came up out of the bag clutching a thick stack of index cards held together by a rubber band. As I knew from experience, this meant that Ali was going to deliver a lecture of the kind he had frequently given on college campuses during the 1960s and now reserved for visitors he deemed worthy of their content, like George Plimpton or Norman Mailer.

It turned out that Ali had a much better idea of who Andy Warhol was than I had credited him with, and that he was determined to make use of the meeting by delivering an important message to him. Over the next forty-five minutes, Ali segued back and forth between two lectures whose titles, “The Real Cause of Man’s Distress” and “Friendship,” might just as well have been plucked from the contents page of The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (Harcourt Brace, 1975). (I have presented his words exactly as he said them, because Ali made a point of thanking me for doing that in a big interview I published with him in Penthouse, and because Warhol taught me that if you did an interview and just let the subject talk about whatever they wanted, however they wanted, that would make the most accurate, revealing word portrait of them. (Warhol was not alone in his theory. The renowned British writer Havelock Ellis wrote in his introduction to Eckerman’s Conversations with Goethe that the interviewer’s job is “to represent the man’s speech as the transparent veil which reveals his personality, so that we are conscious not of a mere succession of opinions on a flat surface but a living, complex person moving in his own three-dimensional space.”) ) Ali started to talk straight at Andy in a way I had never seen Warhol sit still for before.

You’re a man of wisdom and you travel a lot, so you can pass on some of the things I say. See, I’m gonna give you the kindergarten A B C thing. I’m gonna give you a lecture on Friendship and I’m telling you, go out and tell, go out and say, hey this man, he’s got something here, and I’m just giving it to people, I’m giving everyone my leadership after I’m through boxing, so onliest reason I’m fighting these fights is to get the free press.

I mean, I’m going to go into your head now. You might see me punch the bags, you might be white and we live in a world where black is usually played down. It’s not your fault. They made Jesus Christ like you a white man, they made the Lord something like you, they made all the angels in Heaven like you, Miss America, Tarzan king of the jungle is white, they made angel food cake white. You all been brainwashed, we been brainwashed like we’re nothing. You been brainwashed to think you’re wiser and better than everybody, it ain’t your fault. I’m just admit to that. I’m just a boxer, and a boxer is the last person to have wisdom, they’re usually brutes. I’m matching my brain with yours and showing you I’m not going to get on you, but I’m gonna make you feel like a kindergarten child. This black boxer here will make you feel like a kindergarten child. I can give you something more fresh, make you ashamed of your household. I got something here.

I had frequently sat still for Ali’s lectures because they interested me. He was a mesmerizing orator, and nothing critical he said was ever aimed at anyone personally, but this, I could see, was going to be different. As I listened to Ali’s words, trying to follow their meaning, I blanched internally, realizing that Muhammad Ali was going to lecture Andy Warhol on the very same moral crisis in our society that many people had been blaming on Warhol for the last ten years. I didn’t know how he would react, but I didn’t think it would be well. Despite saying that he welcomed all publicity, whether it was negative or positive, the post-shooting Warhol got upset when he was blamed for everything that was wrong in America, especially by someone who was just parroting a party line.

I was equally concerned about Ali. He was used to being applauded regardless of what he said. But now, Andy wasn’t going to look kindly on what he said, and Andy had an unusual ability to cut people to pieces with his eyes. That is to say, by casting a slicing glance at his interlocutors, Warhol was able to discombobulate them so completely that they could not concentrate on what they were saying. They started to repeat themselves, trip over their own words and generally lose their grip. I remember ruefully concluding that it was Ali, not Warhol, who was going to need a buffer. But there was nothing I could do to stop Ali once he launched his attack.

You got rape is high in New York, right? The whole country. Prostitution. Homosexuality. They marching and you’re shocked to see so many. The gay people, all the news and murder and killing. They rob. Everything just go wild. Ain’t no religion seem to have no power. The church is the Pope the everything don’t mean nothing. They talk on Sunday the same song they sing their message. All hell starts back. And everything’s failing. The governments are crooked, the people—don’t know who to trust. And everything’s gone wild—racism, religious groups bombing each other. The Muslims now fighting over in Egypt and Libya, Bangladesh and Pakistan. The whole world is fighting. Everybody’s in trouble, right? So the good lecture tonight [it was noon] is The Real Cause of Man’s Distress and says they’re realities and laws of nature in the world that we all must obey.

In retrospect, this montage—reminiscent of William Burroughs’ The Last Words of Dutch Schultz—probably had as much to do with the incipient brain damage that would soon leave Ali almost completely bereft of his voice as it did with his reactions to any facial fencing Warhol might have thrown at him. One of the points Andy made after we left was how glad he was that “Ali kept looking at me all the time he was talking.”

Without pausing, Ali continued to fire away:

I ask you why we’re having so much crime in the world…Women with their legs wide open, two men screwing each other right on a magazine stand! You can walk down the street and duck in a movie and watch them screwing. Little child sixteen years old go in can watch them screwing and he’s too young to get his own sex so he gotta rape somebody, he gotta watch the movie. You go to NYC and see everything in the movies, every act, oral sex, you sit there and watch it. And the magazine stands are so filthy you can’t even walk by with your children.

[Screaming] Right? Walk down the street and look at it, you got children! Women are screwing women! Men are sucking each other’s blood. Public prostitution on the doorsteps of the White House. Morality in America has been shattered and the social well being destroyed and the powers and facilities which God has left for the good of man kind are being used for bombs and bullets and destruction of mankind. No faith. Man has lost faith in man.

For an uninterrupted forty-five minutes Ali careened through a wide variety of Muslim sayings, “down home” sayings, imitations, digressions and constant repetitions. He talked about gravity, meteorites, jumping out of the window, Israel, Egypt, Zaire, South Africa, drugs, broken skulls, delusions, angel food cake, yellow hair, judgment day, shattered morality, Jesus, boxing, Sweden, the Koran, friendship…Elvis, relating it all to the central point that man must obey the laws of God or perish.

At his best, Muhammad was a master of oratory. He had a beautiful voice, hands and face—the essential tools of a public speaker—and he could work all three simultaneously. At his worst, he sounded like somebody who was reading something he did not really understand.

When I interviewed Ali in the period between 1972 and 1974, he could control his breathing so well he could rap endlessly, take off on limitless tangents and still return to make his point every time. During those years, I sometimes felt as if I was seeing another Martin Luther King in the making. Buy by 1977, four years and nine fights later, Ali was not only missing all his marks, he was rushing his text, losing its rhythm, at times even rendering it meaningless. “I am getting ready to go out and be the next black Billy Graham,” he concluded, somewhat surrealistically.

Ali apparently harbored the belief that if he repeated the same thing over and over again, not only would Warhol come to agree with him, but he would want to help him get on the lecture circuit and deliver these well-meant but unbalanced rants to millions of people around the world. Meanwhile, the reverse was happening. Despite his image as the cool, detached observer, Warhol didn’t like being harassed like this, and he particularly despised any form of paternalism. By now, Ali had pushed all the wrong buttons in Warhol. What he could not have know was that Warhol was not only the consummate listener, he was also the consummate dismisser. The combination of his slicing glance and his I’m-a-stone-statute-just-sitting-here-being-Andy-Warhol-and-nothing-can-penetrate-me act would have thrown anyone who had not seen it before off their spot.

Warhol was as creative an interviewer as he was a filmmaker, In fact, at the outset of his film career, he combined the two forms in a series of films called Screentests. His concept was that if he trained his immobile camera relentlessly on his subjects’ faces while somebody off camera (unheard by the audience) interviewed them about the most embarrassing experiences in their lives, the result would be an extraordinarily revealing, if at times brutal, portrait.

The hard beauty of the Ali-Warhol tapes rears up in their final fifteen minutes. Here Warhol combined his interviewing skills with an homage to Ali-s rope-a-dope technique to create the most revealing voice portrait of Ali in this period of his life that I have ever seen.

Just as George Foreman in the 1974 title fight in Zaire was rendered tired and senseless after pounding away at Ali’s body while Ali laid back on the ropes taking all of the punishment the champion could inflict, so now was Ali rendered tired and senseless after pounding away verbally at Warhol for forty-five minutes while Andy, as it were, lay back on the ropes taking all the punishment the champion could inflict. In all the time I had interviewed Ali or watched Ali being interviewed, I had never seen him as tired, vulnerable and, without meaning to be, as honest as he now became. I’m getting tired of talking,” he admitted ruefully to Warhol, who remained silent.

I’m all right boss, I’m the first heavyweight champion that was his own boss, Ain’t got nobody to tell me when to work, when to train, I don’t have to train today, I don’t have to run—I didn’t run. I can do anything. I can leave town today. I’m free. Herbert Muhammad is the boss, and he never even seen me train, he don’t come to bother me. I’m totally free, I’m the first free black world man they’ve ever had.

This, and everything that went before it, was vintage Ali, but what Warhol really got out of Muhammad Ali that day, which no other interviewer I know of ever did, was the feeling of desperation the champion was beginning to have about getting out of boxing. Again, bearing in mind that the transcription is à la Warhol’s word-for-word prescription, read this with a care and attention you would read a poem: “I mean, no, I’m free, I can’t get fired, don’t have nobody black or white that are my boss,” Ali said.

Y’all can’t do what you want to do. You can’t say take this policy to the TV station or who you gonna tell you got to come do your story, do what they say you do, you can’t take off when you want to take off. I’m the onliest free, black or what, actual entertainer that’s free to do what he want. That’s something. That’s a good feeling. I’m on time. I work. Tell you I’m gonna be here today, I am, right? I just got in yesterday, I’m on time, I’m on my own…So all I’m gonna do, I gotta couple bums to meet, then I retire, get by briefcase, get my stuff, like a Billy Graham, seriously and we got a hundred thousand in Jamaica, Manly, Miscall Manly the Jamaica coliseum, they got a hundred thousand people waiting. Penelton, black prime minister of the Bahamas, they got sixty-five thousand in a soccer field waiting for me.

So by me fighting two more fights, I can do all this preaching, I can get this ministry started, let them know what to look for next. But if I say retire and go call a press conference to tell you all that I want to be is an Islamic evangelist, then they won’t print it, they’re gonna hide it, they won’t let it get out, cause its power to get out, its certain powers. But they gotta do it if I’m in the ring just knowk’em out and grab the mike: “Isamaleka,” means peace on earth to all my brothers of the world. I thank almighty God, Allah, my power, if it were not for Allah, my God, and the power of religion, I wouldn’t be here at thirty-five years old breaking all these records. All my Muslim brothers all colors of all the world, Isamaleka, two billion are watching, “hello,” I call out to all the Pakistanis and Indians, Morocco, Africa, I tell you I know them, So what I’m saying, they rejoice. How can I get that if I don’t fight? If I want a message going on the world beam wire, how’m I gonna, what, President Carter don’t talk to the world. He talk to America, everybody sure be telling you, but he never talks to the world. I talk to the world when I fight, I mean the world is there. So if I fight two more fights, three more fights, I talk to the world three times and I might have forty-five press conferences and you all take pictures of my mosque. If I don’t fight you wouldn’t be here, so boxing and entertaining I use as bait, you go fishing, you put a worm in the water and then the worm, then the fish see the worm you bite it, and behind the worm is a hook, he got more’n he asked for. So I put the movies out, premieres, I pull up in a Rolls Royce in England, my tux here, I get out and me and my wife and all the people looking, they respect people like that. I go to Madison Square Garden, the seats’ll be packed, the stands’ll be packed you’ll see ’em selling popcorn and smoke in the arena, in this corner Muhammad Ali! And I go into my Islamic prayer, promoting my faith, God. But if I wasn’t fighting…so I can just take one more year, three more fights, and get one hundred million dollars worth of publicity, to let the people know what I’m getting ready to go and do.

The way I see it, Andy Warhol painted two portraits of Muhammad Ali that hot day in August twenty-one years ago: There is the silk-screen image on canvas of the fearless champion, his fists curled just below his face ready to snap off a barrage of punches, and there is the voice of the creative rapper, not unlike Elvis Presley in his last days on stage, trying to make sense out of the all-important fact that he is free, along with the fact that he has to fight “only three more fights.” It was sense that Ali would not, indeed could not, have made at the time, precisely because he was not free but was in fact the unwitting captive of the parasites who had attached themselves to him since the 1960s. These leeches who chose his doctors, lawyers and financial advisors siphoned as much cash as they could from him, careless of his well-being, his health or the future.

With his gift for deftly putting things in perspective, Warhol did not utter a word until we were out of earshot but still in sight of Ali. Before the limousine that had brought us to Fighter’s heaven cleared its parking lot, he was all over me with his reaction and one central, jabbing question:

His problem is he’s in show business. It’s hard to get out. I mean, it’s like, he could be threatened. But I’m surprised fighters don’t take drugs, because it’s just like being a rock star. You get out there and you’re entertaining thirty thousand people. I mean, you’re a different person. I think that’s why Ali’s different. But what did he say? Two guys sitting on a what? Why throw that in? That’s so funny. I think he’s a male chauvinist pig, right? He’s a male chauvinist pig? Because, I mean, how can he preach like that? It’s so crazy, he just repeats the same simplicity over and over again, and then it drums on people’s ears. Maybe he was just doing it especially for us. I don’t know. It’s so crazy. But he can say the same things because he’s so good looking that he has something more than another person does.

It was good to see, but it shouldn’t have been so long. I think he was just torturing us.

What I can’t figure out is, is he intelligent” I know he’s clever, but I mean, is he intelligent? Is he intelligent? That’s what I can’t figure out.

_____

This article first appeared in the April 1999 issue of Gadfly Magazine