Two flight attendants bobbed down the aisle with gyroscopic grace as our plane taxied off the Pearson runway toward a squad of chemical trucks. They smiled, waving little bundles of wire in clear plastic wrappers as an offering from CrossCan. I frowned at the window – the Plexiglas was already steamed over by the exasperated breathing of the human cargo, forced to suffer the indignity of a twenty-minute deicing procedure. Outside raged a storm lit up in streaking currents by the pulse of the wing lights. I could think of only one thing as I stared into the blizzard: my father’s abrupt death. Try as I might, an awareness of this reality would not come into focus before my mind’s eye. Instead, it hung like a vacuum in my chest, a negative weight pulling my organs out of place. The concept hid in a blind-spot of sensation, leaving me empty when I reckoned with it.

Dad was happy and healthy the last time we spoke, though it seemed like years since our conversation a week prior. The call had been typical – work at the hardware store was the same, Mom had her diabetes in check, etcetera. He was always chipper on the phone, always a little corny. He told me about the dogs and the long walks they had taken recently. Madeline had developed a grey patch around her muzzle that betrayed her age. After asking about my sex life, Dad found an excuse to hang up. Snow would fall that evening, according to his digital weathervane, and he wanted to clear the walks before bed to make shoveling easier in the morning.

I wiped the film of condensation from the window with the sleeve of my sweater. A tanker truck sat at the end of the wing like a giant yellow scorpion, pumping antifreeze to a boom operator at the tip of its tail. Emerald green spread in waves across the white control surface as the flight crew manipulated the ailerons and braking flaps up and down, spreading antifreeze throughout the machinery from the comfort of their cockpit. It looked to me like a close-up shot of a duck in an oil spill. I pulled down the plastic blind. The kid seated next to me squirmed to get a better view of the storm out the window in the next row.

Getting a last-minute ticket from Toronto to Calgary was relatively easy once I told the booking agent the reason for my haste. Annie, my big sister, had called with the news that morning. She and Dad had not been on the closest terms for the past several years – not hostile in any sense, but not intimate either – making her the person I was least prepared to hear it from. This fact stunned me for most of the afternoon, and the sun set before I could drag myself to the airport. I had to meet Annie in Calgary and move onwards into the mountains. The last flight that evening was booked solid, yet the agent shuffled things around out of professional sympathy. He checked my suitcase with a terse smile, eyes averted, and wished me a safe journey.

My parents retired to Creston, a valley town of five thousand in southern BC, when Dad sold his contracting business ten years ago. He and Mom consolidated a life-time of possessions into a truck and trailer for relocation to the Rockies, which seemed natural as the mountains featured prominently in our family history. We vacationed every summer at my grandparent’s cabin on Kootenay Lake, that is, until the campground was purchased from the elderly owners by a property development firm and converted into a resort. Childhood summers stretch into magical, nostalgic eternities. Life has a powerful immanency in the wild, away from television and skyscrapers and the concerns of society. Nature relieves you of past baggage and future worry. Summers spent swimming in a glacier-fed lake amid the evergreens left the lasting impression that clocks don’t have the authority everyone pretends they have. I was fourteen when we stopped going to the cabin and the part I miss most is the timelessness of dusk in the shadow of a mountain. And then, when the glow of the sun has faded behind the jagged peaks, stars litter the night sky like a banner, solid and radiant overhead.

“He would not have wanted you to see him like that.”

Annie’s words resonated in my mind as I watched the airplane’s pit crew labor in the stroboscopic storm. I couldn’t understand what she meant. She had told me what happened. She had watched as he died. Annie drove from Calgary to Creston the night before to be with Dad in the hospital. The trip took five and a half hours, but Annie made it in four, and I doubt anyone could have made it quicker. When she got there, Dad was unconscious in the ICU. His abdomen was split open across the belly, intestines vacuum-sealed to his body in a blue plastic sack to prevent their leaking out any farther, tubes and pumps and wires threading in and out of his flesh. He convulsed in pain towards the end. Annie said the doctors gave him anesthetics to help him cope, and in the space of an hour our father was gone.

“He would not have wanted you to see him like that.”

Did she mean mutilated and dying? It struck me as odd that she would say such a thing. Of course he did not want me to see him hemorrhaging to death in a country hospital. It would have been the most horrible and undignified hour in a good man’s life, but Annie somehow managed to be there. And after all that, she drove back to Calgary to pick me up, which made me wonder: could I have suffered my father’s mortality with her strength? Could I have borne that weight?

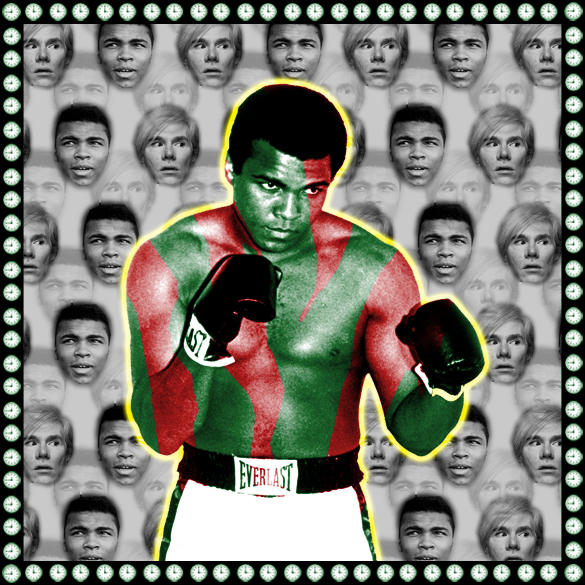

I opened the blind. The tail of the chemical truck, poised over the wing, began to withdraw, and the yellow monster backed blinking and chirping into the obscurity of the storm. The pit crew waved us on with halogen flares which cut through the gloom in swooping arcs. Inside the cabin, a tone chimed and the seatbelt light switched on. The child next to me, a boy of about seven or eight, turned and peered intently out the window. He leaned over me a little, trying to get a better view of the situation outside. I tensed up, bringing my hands into my chest like a boxer taking a torso beating. Kids have always made me uncomfortable – I wouldn’t want to spoil one by accident. He noticed and looked up into my face, inquisitive, without recoiling an inch. His eyes were neutral and disinterested, but his mouth turned up a little at the corners. He was amused by my discomfort. I relaxed a little as the plane began to creep forward and he left my personal space, occupying himself with the entertainment unit in the headrest in front of him. We were returning to the runway, and onward.

I had been to only one funeral before, that of my grandmother. We didn’t spend a lot of time with my mother’s family when I was a boy as they lived in different places around the country and only came to town over Christmas break. Grandma lived in Calgary, yet she spent many of the holidays celebrating at the Legion with her friends, dancing in line at the terrible buffet. I don’t blame her for it in the least. She smelled of too much perfume and wore an obscene amount of make-up and jewelry – her favorite stone was turquoise and it always amazed me how much of it she procured. I enjoyed being around her, but we didn’t talk much. We didn’t have anything in common; too wide of a generation gap, I suppose. She was eighty-two when she slipped in an icy stairwell and was taken to hospital with a bruised lung. The internal bleeding wouldn’t stop, and soon her lungs ceased to function on their own. I saw her in the hospital before she died. Dark purple bruising had spread across her chest, while the rest of her was as pale as parchment. A breathing tube fed her the oxygen she needed to stay alive, but the ugly mark seemed to spread up her pale throat as I watched, helpless.

When she died, many of the people who came to pay their respects were completely foreign to me, but I was glad Grandma had such a wide group of friends to celebrate her. The viewing was the most surreal part. It felt like a dress rehearsal, a dream of the real thing. Grandma had lost all traces of the suffering I had witnessed a few days ago; she looked like a wax statue under the fluorescent lights in the funeral home. I was tempted to reach into the coffin and touch her cheek. Instead, I satisfied my morbid curiosity by hanging around near the open casket, observing how people reacted to Grandma’s dead body as they leaned in to say goodbye. Mom rallied a surprising amount of dignity and courage when it came time to speak. She delivered her eulogy with confidence and a poetic tenderness I would not have thought possible. After the service, it was my turn to participate in the funeral. I was a pall bearer along with Dad, my uncle Barry, and some relatives I had never met. Our first duty was to lift the casket into the back of the hearse. It was far heavier than I expected, and I groaned inadvertently under the weight. The black box slid into the vehicle on metal rollers hidden in the floor of the trunk. I noticed then the countenance of a hearse is well suited to its purpose; morbid in a subtle sort of way, like the silhouette of a shark. We followed it into the back corner of the cemetery, blocked from the prying eyes of passing motorists by a copse of trees beyond a chain-link fence. The icy ground crackled underfoot as we carried the casket across the frozen grass between the gravestones. I don’t remember what the minister said as we lowered Grandma into the ground, only the frost prying its way into my borrowed dress shoes and Dad smiling supportively across the lacquered lid of the coffin.

Static hissed over the intercom as Flight 206 rolled to a stop. The captain sentenced us to additional time in purgatory between apologies on behalf of the airline. There were runways to be plowed and incoming planes to land. Of course, another round of exasperated groans spread through the aircraft. Passengers tsk-tsked and tapped their feet in impatience. I felt a specific emotion for the first time that day – dread – and my diaphragm seized up at the possibility of missing Dad’s funeral. It was an irrational fear, considering Annie would never have left Calgary without me after having driven all the way back, but I was not thinking straight at the time. Panic signals diffused through my nervous system, spreading out and settling into my muscle fibers like soldiers into foxholes. I fidgeted and bit at my nails. Missing the funeral of a family member is uniquely challenging, as I learned firsthand when Dad’s dad passed away. Grandpa had suffered the cruel effects of dementia for years, drifting slowly away from his wife and the muddled world around him, and I felt a shameful sort of relief when Dad called with news of his passing. He died in his sleep when I was twenty-two and working on a bachelor’s degree in Halifax. Dad and I decided it would not be necessary that I come back for the funeral, considering Grandpa’s death had been a long time coming and I was right in the middle of midterms, but this decision had unforeseen consequences on my ability to find closure. The last memory I have of Grandpa is this: my aunt stands behind his recliner, struggling to trim his shock of white hair as he smiles at her frustration, chin wet with drool. He hadn’t recognized me that day.

When we laid my grandmother to rest, the whole family came together in an unflinching nucleus of support. Though it was a strange experience, we bonded in a way we never had before and I was able to make peace with her death. Now I look at my memories of her without sadness or grief. This is why not going to Grandpa’s funeral became a problem – every time his memory is recalled an old wound is reopened. I can’t think of his life without the ignominy of his death, and it breaks my heart. This heartbreak, this lack of finality, informed my terror at the further delay of Flight 206. I could not possibly cope with losing Dad if I did not get the chance to say goodbye. And yet, things would be different from Grandma’s funeral. Dad always wanted to be cremated. He mentioned it many times over the years, but I still remember the car ride when he made me promise to uphold this wish no matter what. We were driving to pick up my first vehicle, a red Ford Ranger, from a family friend’s ranch north of the city. I was looking out the passenger side window, watching the canola fields fly past in a yellow blur. Dad turned off the radio and rolled up the windows before making me promise to burn him. He seemed to think it would make the grieving process easier on us because we wouldn’t be exposed to his dead body – an idea I supported until I realized, while trapped on the plane, that I would never actually see him again. Sure, the service would have photographs from his life and the urn with his ashes would be there, but I wouldn’t get that finality which comes from looking into an unresponsive face or holding a cold hand. I decided then that, when I die, I will have a viewing for the sake of my loved ones, even if they cremate me after.

“He would not have wanted you to see him like that.”

Again Annie’s words came into my head. Maybe she was right. Maybe Dad never wanted to be looked upon after death, regardless of how it came about. He was never one for dramatic displays, and most likely wanted us to move on from his passing as quickly as possible. Dad was a modest type who funneled his emotions into his work, and I can only imagine his embarrassment at the attention he would receive at his funeral. I, for one, intended to give him an appropriate eulogy. After spending my twenties trying to outlive my father, to exceed him in every quantifiable way, I realized that even living up to Dad’s life would be an achievement. He was happily married, financially secure, and in possession of a humble sort of morality which I never saw tarnished. More importantly, he had the love of his family and friends, and the enjoyment of their company was his greatest pleasure. In spite of this new-found appreciation for the life my father lived, the concept of his mortality was not new to me, and I had thought long and hard about the kind of man he was well before he died.

The first time my father’s eventual death became really tangible to me was on the come-down from an LSD trip. Dad renovated houses before moving out to Creston, often laboring at a jobsite by himself. As I lay curled up under the covers of my bed, twitching out the last of the acid, I let my consciousness wander into some dark recesses which had never been explored before. I saw Dad working in an unfinished basement, sliding a sheet of drywall away from the stack of gypsum boards leaning precariously against a wall. He wore a tattered, yellow baseball cap and a dirty knee-brace, both relics from a promising high school football career. It was getting late, but it wasn’t unusual for him to stay after dark if the homeowners were away, and my Mom didn’t stress if he missed dinner every now and then. I watched as the stack of drywall sheets tilted away from the wall, wobbling slowly, and toppled over, crushing my father’s leg and pinning him to the concrete floor. He would lie there, bleeding and calling for help in the empty construction site, cellphone just out of reach, until his body couldn’t handle the strain and he passed out. Mom would have an anxiety attack and file a missing person’s report, but she was completely ignorant as to where Dad worked from day to day. The homeowners would find him a week later, white as the gypsum he had been installing and cold as the concrete he lay upon. The vision mortified me, for it came from my own mind, but I reassured myself Dad’s end could not be as violent as I had imagined. But I was mistaken, which I realized as the plane started moving again.

The intercom crackled platitudes about trip time and average flying speed as our plane turned left onto the Pearson runway and began to accelerate, sending vibrations up the landing gear, through the chassis, across the floor, and into my guts. The noise and tremors served to augment the anxious tension taking over my body. Paralysis crept into my limbs, wearing me like a white-knuckled puppet. I had been wrong about the degree of violence Dad would have to face at the end of his life, even after preparing for the worst. Dad worked at the hardware store on the north side of Creston as a way to fend off the boredom of retirement. It’s a small shop, requiring only one employee to run it on slow afternoons. He was there by himself, minding the place, when a man with a shotgun burst through the door. It was the middle of the day, and yet the man held my father at gunpoint, forcing him to empty the till and load several power tools into a duffle bag. Dad did all this without resisting, as is clear from the surveillance footage. When he had what he wanted, the thief shot my father in the stomach at close range and fled the store. The buckshot tore my dad’s abdomen open and shredded his intestines. This is an almost certain death-sentence in the best of scenarios. A vendor from the market down the street reported the shot and Dad was rushed to the tiny Creston hospital. By the time he was put onto life support, the thief had been caught trying to cross into the United States, speeding south on the Creston-Rykerts Highway. There was nothing anyone could do, and Annie is fortunate to have seen him out.

The rumbling got louder as Flight 206 picked up speed, engines whining in the wind. Blue lights marking the edge of the runway flickered in the window as we hurtled past. We were leaving. I would soon have to face my father’s ghost and say goodbye. I would soon have to see where he was murdered, where he was torn from us by the senseless actions of one man. The very thought impaled me. We moved faster and faster and fear tightened its grip on my heart; real terror like I had never felt before. Hot tears streamed down my cheeks. Stop the plane. Let me off. I can’t handle this. I’m going to die on this flight. No longer able to endure the lights streaming past the window or the cacophony of the engines, I twisted toward the boy next to me, sobbing, desperate, and completely helpless.

His face was calm and his gaze steady as he watched me cry. I saw my sorrow reflected in the pools of his eyes, floating there like tiny islands in a blue sea. He looked into my face, taking in the despondency and misery written there with a child’s suspension of judgment. I felt the world shaking under me as in an earthquake and the wind howling by like a hurricane. And suddenly, none of it mattered anymore – my suffering, Annie’s words, the senseless violence, the fear of goodbye – it dissolved into his eyes. The kid saw my pain and simply accepted it. I knew then that everything would be alright, that I would overcome this, and that nothing and nobody could rob my father of his dignity. My responsibility is to support Annie and Mom through this difficult time, and I will rise to the task. I’ll have the power to live well, like my Dad, and the duty to honor him.

One of Dad’s maxims came back to me as the kid returned to his entertainment console, wearing the same strange smile as before. Dad always said the best part of a flight is the moment when the wheels leave the ground – all the clamor and shaking from the journey down the runway stops short and, for a moment, one silent instant, the whole world is weightless.

—

Kyle Flemmer is a student at Concordia University in Montreal double majoring in Western Society & Culture and Creative Writing. He founded The Blasted Tree Publishing Company in 2014 as an outlet for his writing and to build a community and support network for emerging Canadian artists. Kyle is passionate about social satire and philosophy and enjoys writing short stories, poetry, and critical essays. Other hobbies include DJing, tattooing, and the unmitigated pillage of second-hand book stores. Check out theblastedtree.com for more.